Category: BULLETIN

BULLETIN

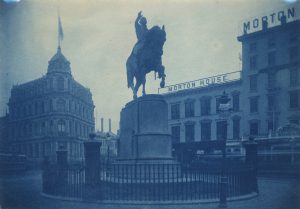

GEORG KOPPMANN

Vintage Photographs of Historic Hamburg

Architecture & Photography

Nineteenth-century German photography is represented only by a small number of photographers, who appeared to have worked mainly in Italy. They were fascinated by the great wealth of the Italian architecture and by the antiquities found nearly everywhere in the country. This makes Georg Koppmann’s photographs that much more noteworthy, documenting as they do not only a Hamburg which no longer exists, but a moment in the history of photography, artifacts and historical studies in and of themselves. These photographs are a valuable source of knowledge for a great city’s architecture, both as documentation and representation.

From the very beginning, photographers have explored architecture as a primary subject. One of the first surviving photographs takes an architectural theme, a view captured by Joseph-Nicéphore Niépce in 1827, across the rooftops of his property. When the printing process was further improved following the collaboration between Niépce and Daguerre, albums could be published, bearing photographs of the world’s great monuments in Egypt, Nubia, Palestine and Syria, in Greece, Spain, Italy and France. William Henry Fox Talbot’s earliest surviving photograph has an architectural subject, too.

Drawings offer a useful source of information about architecture, allowing us to peer over an architect’s shoulder, and, thus, making it possible to trace the design and development of a building. Photographs, however, provide an immediacy and accuracy of representation. Talbot – considered the inventor of the negative process – wrote in 1845 that “even accomplished artists now avail themselves of an invention which delineates in a few moments the almost endless details… which a whole day would hardly suffice to draw correctly in the ordinary manner.”

Photographers also were commissioned by municipal and private agencies to document old buildings on the cusp of demolition, in urbanization and modernization’s path. The systematic documentation of Paris by Charles Marville shows whole streets and neighbourhoods being destroyed as entirely new areas of the city are developed in their place. Georg Koppmann’s photographs show historic streets, buildings, canals and bridges of Hamburg just before they were torn down for the imminent construction of the city’s famed warehouse district – the Speicherstadt.

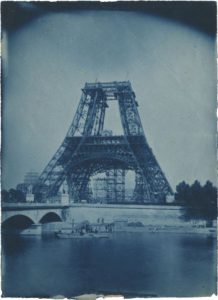

Speicherstadt

Speicherstadt (“Warehouse District”) is the world’s largest complex of warehouses, with an area of 260,000 square metres. It was built into the Elbe River between 1883 and the late 1920s, on thousands of pilons, as a free economic zone in Hamburg’s port. In 2015, Speicherstadt, Kontorhausviertel and Chilehaus became Germany’s 40th UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg became part of the German Empire in 1871, but for a time it was able to maintain its own tax and customs regulations. This privilege remained in place until 1881, when a new customs union was installed. From this point on, only the free port area along the Elbe River remained exempt from import sales taxes and customs. Final annexation of Hamburg by the German Empire was scheduled for 1888, allowing the city seven years to create new storage facilities inside the free port area. In order for construction of the warehouses to begin, which it did in 1883, around 24,000 people had to be evicted, and around 1,100 houses torn down.

In 1888, Emperor Wilhelm II inaugurated Speicherstadt, although only the first building phase had been completed. Interrupted by World War I, construction lasted all the way until 1927. During World War II, Operation Gomorrha destroyed the western part of the district. Reconstructions lasted until 1967. Finally, on January 1, 2013, an era came to a close, and the free economic zone of Speicherstadt, covering almost a fifth of the area of Hamburg’s entire port, was dissolved.

sources:

Richard Pare, Photography and Architecture: 1839-1939, Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal 1982. www.hamburg.com

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Find all exhibited images here

Other Diversion

'3 Hamburger Frauen' Artist Collective Georg Koppmann Prize Hamburg

Housing Projects by Lüpertz, Kiefer and Immendorff

Architecture & Art

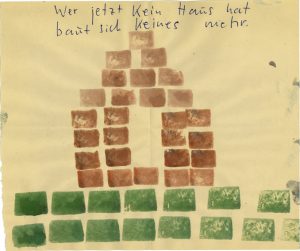

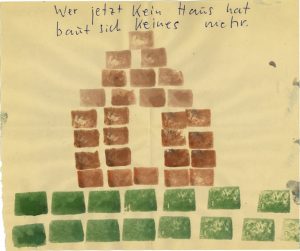

The painting career of Markus Lüpertz (b. 1941) begins with the discovery of the “Dithyramb” – a term from the poetics of the antique world, originally denoting a form of song in praise of Dionysus, God of Wine, and which has come in common parlance to describe an attitude of exuberance towards life, of a passionate ‘inspiration’ and ‘drunkenness.’ The post-war period was marked by a hesitant and even over-cautious restraint, which over time began giving way to a taste for strength and dynamic drive in art. Lüpertz’s decisive artistic disassociation from the environment around his applied arts school in Krefeld, and the beginning of the Dithyramb, belongs precisely to this moment in history. The interpretation of the Dithyramb as an architectural idea, as a house of diverse materials and parts, stems from a series of linear Dithyramb constructions in chalk dating to 1964, a series including the sheet shown here. Building blocks, shadowed all around in blue and white, form themselves into a grid, which itself is fractured and inserted into flat tiles. A new possibility begins to hint at itself, the possibility of releasing shape and form into the third dimension.

After an absence of several years, Anselm Kiefer (b. 1945) first returned to the public eye in 1973 with a series of pieces containing references from the bible, Germanic mythology, and the literary canon. These works are – as is characteristic of his entire oeuvre – inscribed with descriptions, names, and quotes.

“I view my pictures as ruins, or like building blocks, things which can be put together. They are the material with which you can build something, but they are not complete. They are closer to that which does not exist than they are to that which is completed.” – Anselm Kiefer.

The neo-Dadaist project “LIDL,” created by Jörg Immendorff (1945-2007) and Chris Reinecke, set out with the goal of bringing art and politics together in a tangible way, attempting to make alternative, artistic concepts accessible to a public outside of and with limited engagement with the prevailing currents of the world of art. In 1968 Immendorff designed a minimalistic concept for his “LIDL”-city: little houses of wood and packaging paper, within which the “LIDL”-commune would live. The “LIDL”-Academy is among the most famous actions taken as a part of the artist’s early “LIDL” period. Immendorff and some kindred spirits declared it open within the Dusseldorf Art Academy on December 2, 1968, in the wake of a row that had broken out regarding an open letter published by ten professors which accused Joseph Beuys of seeking to use the German Student Party (which he helped to found) as a tool to exert influence over the Academy’s curriculum.

sources:

Siegfried Gohr, Markus Lüpertz. Zeichnungen aus den Jahren 1964-1982. Ausgewählt von Siegfried Gohr und Johannes Gachnang, Bern/Berlin 1986.

Josef-Haubrich-Kunsthalle Köln, Markus Lüpertz. Gemälde und Handzeichnungen 1964-1979, Ausstellung 01.12.1979-13.01.1980.

Theo Kneubühler. Anselm Kiefer, in: Kunsthalle Bern, Anselm Kiefer. Bilder und Bücher. Ausstellung 07.10.-19.11.1978.

Toni Stooss, Des Malers Atelier, in: Götz Adriani, Anselm Kiefer. Bücher 1969-1990, Tübingen/München/Zürich 1990-91, S. 24-33.

Kunsthaus Zürich, Jörg Immendorf, Immendorf, Ausstellung 19.11.1983-22.01.1984, Zürich 1983.

art Magazin 07/2001: art-magazin.de

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

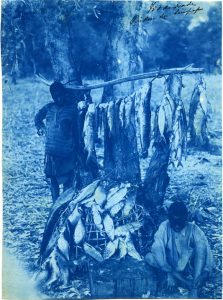

Francis Frith’s (1822-1898) photographic tours to Egypt in 1856-57 and 1859-60 were by far

the most ambitious and systematic excursions of his time

A Victorian Photographer Abroad

The Photographic Voyage of Francis Frith to Egypt

“Following my bent toward the romantic and perfected past, rather than to the bustling and immature present, I went East. … I would begin at the beginning of human history: I would track the Sun back to rising, and see the lands upon which his first beams fell. … It would, of course, be easy to fill my book with details of these bewitching wanderings, the memories of which are worth, to me, moutains of gold and silver.”

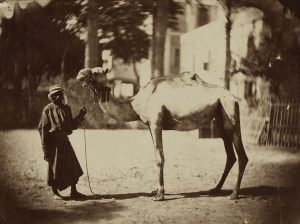

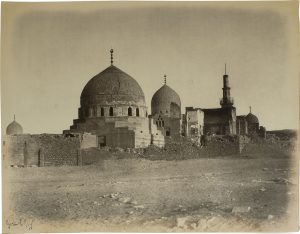

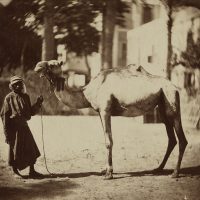

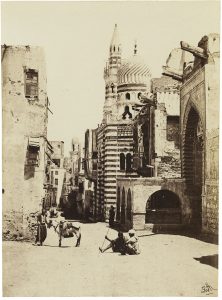

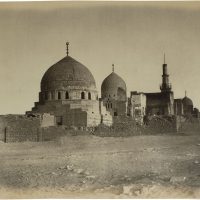

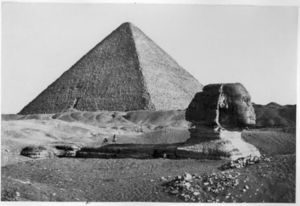

Francis Frith’s (1822-1898) photographic tours to Egypt in 1856-57 and 1859-60 were by far the most ambitious and systematic excursions of his time. By the time he left Liverpool for Egypt, Frith was already a recognized photographer.

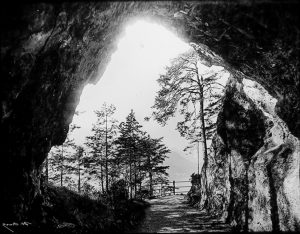

His first experiments with photography are to be dated between 1851, when Frederick Scott Archer’s wet-collodion process was made generally available, and 1853, when Frith is recorded as a founding member of the Liverpool Photographic Society. Only a few years of practical photographic exercise later, he set out on his first Egyptian journey. The expedition was thoroughly planned, costly, elaborately outfitted, and conducted at a leisurley pace. Frith brought with him his stereo, the whole-plate and his mammoth-plate cameras, of which the latter was situated inside a covered vehicle which also functioned as portable darkroom and as a shelter. “We did not,” Frith wrote, “anticipate much in the way of successful results, for, as far as we were aware, we were the first to carry the process into hot countries.” At this time, the wet-plate process was still untested in desert conditions. The climate made the photographer creative, “Many of my photographic pictures were made in tombs! to save myself the trouble of pitching my dark tent, and also for the sake of their greater coolness, I very often availed myself of a rock-tomb.”

“Notwithstanding all that I had read and imagined, I was not in the least prepared for the extraordinary and brilliant novelty of the scene that burst upon my eye on first landing in an Eastern port. … Alexandria was the greatest ‘sensation’ that I had ever experienced.”

Over the course of the group’s months-long tour, Frith photographed sites throughout Upper Egypt, including Aswan, Gebel el-Silsila, Edfu, Armant, and the Cataracts of the Nile. However, the majority of his subjects were found in the vicinity of Thebes, Luxor, and Karnak, before travel continued on to Cairo and the Great Pyramids. By then the summer season was approaching, and the climate was growing inhospitable. In July 1857, Frith returned to England, carrying with him his first set of negatives, ready for printing and exhibition.

The second voyage began that November, with Mediterranean temperatures now subsiding. Together again with the other travellers, the trip back to Cairo was made by steamship, and Frith started his photographic work anew on Islamic mosques, tombs, and Cairo street scenes. Frith probably spent the winter in Egypt before traveling to Jaffa sometime in early 1858, where the group spent more than a year. In July 1859 they “spent a summer in Cairo and its neighborhood, sweltering in an occasional heat of 108° to 110° Fahrenheit all through the night.” The new series of negatives continued with subjects like mosques, cemeteries, the Citadel, street views, flora and fauna, the pyramids, the Sphinx, the tombs at Sakkara and Dahshur, the pyramids at Giza, the stone quarries of Tura, and the Temple of Kalabsha.

With his departure for the voyage home in the early summer of 1860, Frith left behind what he considered his last “grand spell of sunshine” and readied himself for the responsibilities of marriage and business that awaited him in England.

source: Douglas R. Nickel, “Francis Frith in Egypt and Palestine. A Victorian Photographer Abroad”, Princeton University Press Princeton, New Jersey/Woodstock, Oxfordshire 2004.

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

Autochromes and the Lumière brothers EMOP Berlin Helmut Newton Foundation

“Travel to Egypt? They all start dancing with sheer joy,” he wrote.

“As if that was something other than going to London.”

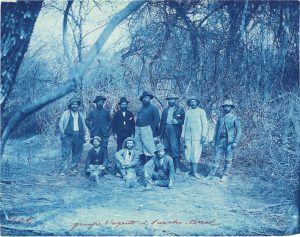

Traveling Photographers

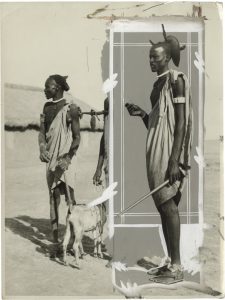

Photography from The Travel Bug of the Nineteenth Century

In 1824, Eugène Delacroix was still critical of the newly emerging interest in travel to the Middle East, “Travel to Egypt? They all start dancing with sheer joy,” he wrote. “As if that was something other than going to London.” Only a few years later, in January 1832, Delacroix left France to journey to the African coast himself, in support of Charles Henri Edgar, Count of Mornay’s diplomatic delegation to Sultan Abd al-Rahman. The delegation was mandated by the government of King Louis Philippe to start a dialogue concerning the political events of adjacent Algeria. The vague political situation in the nineteenth century required numerous diplomatic missions, which were often accompanied by artists or photographers. Thanks to these contemporary witnesses – solo travelers as well as documenting escorts – the western world learned about the countries of the Far and Middle East. However, not only the artworld profited from these long-distance travels. Steamboat and railway reduced travel time and offered a new degree of comfort and luxury. Shipping lines like the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Company were established as a regular link between England and Egypt. From 1883 the Orient Express ran on the route from Paris to Constantinople. Travel agencies like Thomas Cook recognized the trend and acted accordingly by offering guided journeys to the Orient.

Gustave le Gray (1820-1884) is considered the most important and influential photographer of the second half of the nineteenth century. His photographs are so rare and highly collectable that many have set record auction prices. Le Gray studied painting with Paul Delaroche. His interest turned to chemistry and photography and by 1855 he had won the high accolade of the “Medaille de Première Classe” at the Universal Exhibition.

Maxime Du Camp (1822-1894) took photography lessons from Gustave le Gray and travelled in 1849 with Gustave Flaubert to Egypt. His journals and subsequent books, such as Le Nil (1855), along with Flaubert’s letters and travel notes, provide one of the most complete accounts of the European experience of Middle Eastern travel and of the daunting enterprise of making photographs during the early years of photography.

Francis Frith (1822-1898) was the most well-known nineteenth-century photographer who travelled to the Middle East. On two of his three excursions to the Middle East he visited Egypt, first in 1856-57 and later in 1859-60

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

Robinson Crusoe, Tom Sawyer & Huckleberry Finn, Treasure Island and Moby Dick Museum Fünf Kontinente - Database Photography online Music for Wanderlust

One of the most common printing processes developed in the 1850s is the carbon print.

Carbon Printing

In 1839 the invention of photography was formally announced. In the previous years many chemists, inventors and artists had worked on finding a method of capturing an image by the agency of light alone. Eventually, two processes reached a state of development that allowed the reproduction of images and spread the new technology throughout society. One method – invented by Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre – enabled the photographer to capture lens images on silver-plated sheets of copper. The other one, invented by William Henry Fox Talbot, provided the opportunity to produce images on paper. These early methods are characterized by their dependence upon the sensitivity of silver compounds to light.

One of the most common printing processes developed in the 1850s is the carbon print. This process is named after the use of carbon black as a coloring agent, however, any other pigment would also work. The underlying method of the carbon print is based on a thick layer of gelatin which holds the pigment and is sensitized to light with a dichromate salt and exposed by contact to a photographic negative. The lighter areas of the negative expose the gelatin layer more to light than the dense areas. After the exposure, the unexposed gelatin can be washed away and a positive print, made of pigmented gelatin, will result. In the family of early photographic printing techniques carbon prints are the most stable and the only practical photographic process to produce monochromatic prints that use any of the color pigments commonly available to artists.

The first discoveries in this pigment printing process are credited to Alphonse Poitevin, a French chemist, engineer, inventor and photo pioneer. As such, Poitevin is regarded as the inventor of carbon printing. Poitevin and other colleagues and contemporaries, like Honor d’Albert, Duc de Luynes or Alphonse Braun continued these experiments and laid the foundation for all subsequent methods of pigment printing.

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

August Sander.Sardinien 1927 - Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich Anish Kapoor at Pinakothek der Moderne

The photographs taken by a machine are the remnants of one the first successful attempts

at exploring our nearest celestial neighbour.

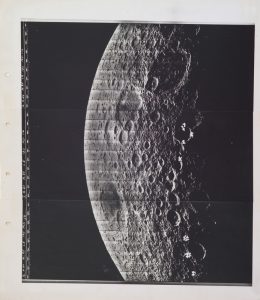

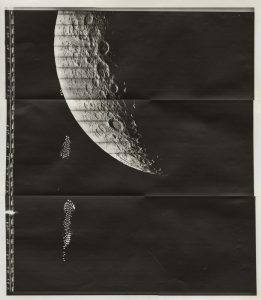

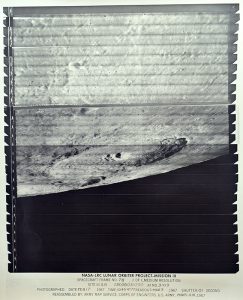

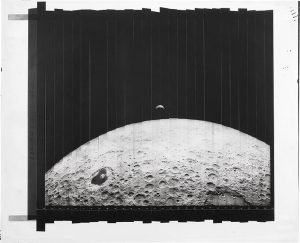

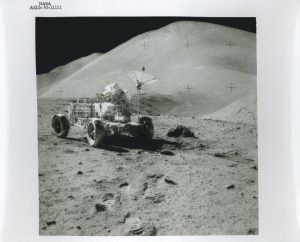

So far yet so close: NASA Lunar Orbiter Photographs

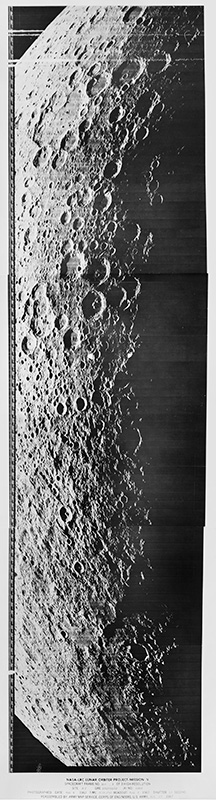

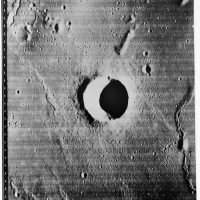

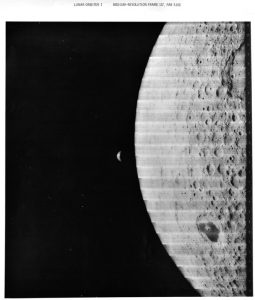

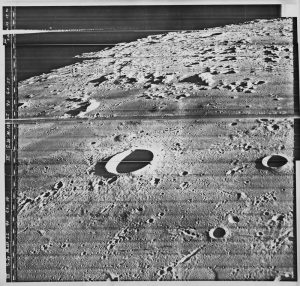

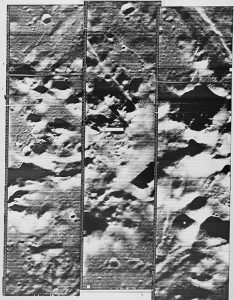

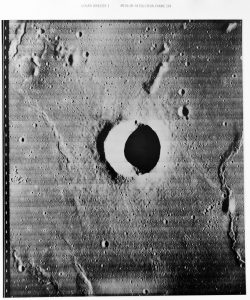

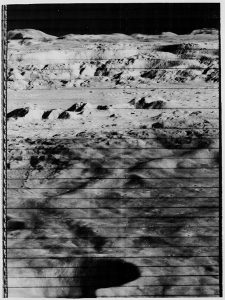

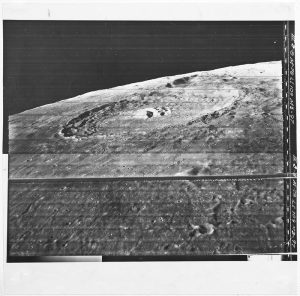

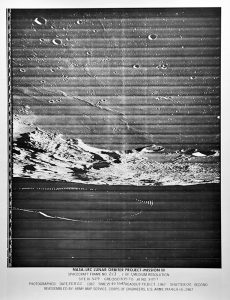

Mapping the surface of a planet does not sound impossible nowadays. But what if we were to go back in history by about half a century? The Lunar Orbiter missions, launched by NASA in 1966 through 1967, provided humanity with an invaluable trove of knowledge about the Moon’s landscape. Different parts of the satellite’s surface were laboriously documented by five spacecrafts during this period. These were the first images from the lunar orbit that included photographs of both the Moon and the Earth.

The photographs taken by a machine for an astronomical research mission are the remnants of one of humankind’s first successful attempts at exploring our nearest celestial neighbour. These monochromatic images display our rocky satellite’s surface from different angles and altitudes and with variations in lighting. Some show the Moon in its near-entirety, clearly revealing the “border” between day and night. Stark contrast of shadows and light on the contoured wasteland reveal gaping black holes: the craters that the missions were surveying. The images convey the silent immensity of outer space. In some, we see the Earth from a lunar perspective: proof of how isolated our Blue Marble really is. We are presented here with an altogether unique aesthetic, made possible by the perfect geometries of our celestial bodies, the play of light and shadow and the historically monumental nature of the Orbiter missions.

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

Museum of Moving Image - Envisioning 2001: Stanley Kubrick's Space Odyssey Queens Museum - Bruce Davidson: Outsider on the Inside The Morgan Library and Museum - Beethoven 250: Autograph Music Manuscripts by Ludwig van Beethoven Chateau de Versailles - Fountains Shows and Musical Gardens

“Images enlarge the space, expand it – form tunnels into other worlds,

make the room a Charles de Gaulle departure hall”

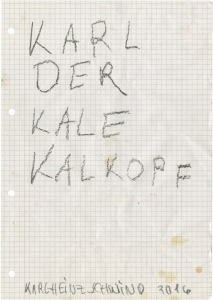

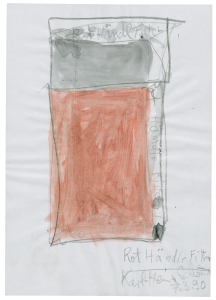

Karl-Heinz Schwind

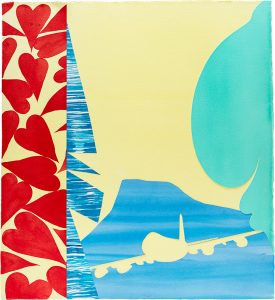

Karl-Heinz Schwind (*1958 in Landau) studied under Georg Baselitz from 1978-84 and was a master student of Per Kirkeby at the Karlsruhe Art Academy from 1984-85.

His colorful, strong works, some of which border on material battles, contain numerous quotes from art history. Schwind tries it out – that’s his style. His works show the political and cultural tensions of West Germany in the 80s. He finds endless inspiration in his surroundings: people, commuters, Berlin tourists, the community. And Milva’s music.

To question himself and society – this is what Schwind has been working on in his painting to this day. He is not afraid of references, thematically he incorporates Ludwig Kirchner into his works, just as quotes of Dadaism and technical transformation of Tachism.

He follows an inspiration almost archaically, anarchically and creates work out of what falls into his hands: wood, magazines, wax crayons, canvas, yarn.

Schwind lives and works in Berlin.

From the catalogue of the first exhibition by Daniel Blau, Munich 1990: “Images enlarge the space, expand it – form tunnels into other worlds, make the room a Charles de Gaulle departure hall”.

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

Albertina - Die frühe Radierung. Von Dürer bis Bruegel Staatliche Museen Berlin - Raffael in Berlin. Meisterwerke aus dem Kupferstichkabinett Kunstgewerbe Berlin Music video by Milva performing Freiheit in meiner Sprache (Official Video). (C) 1999 Sony Music

There are just a few examples of the ways in which artists have turned

their attention to cars and car cultur

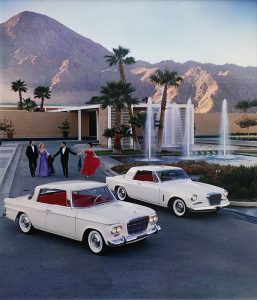

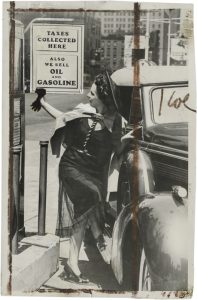

auto – Mobile

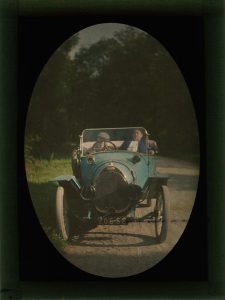

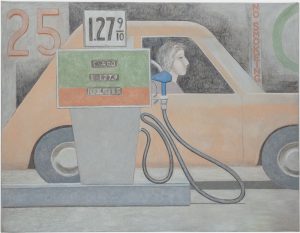

Cars, steam engines, aircraft and space ships proved endlessly inspiring to early and modern photographers and artists, who documented the new vehicles and the journeys they enabled. A new kind of landscape photography emerged, situating man and his machines in the context of rural, urban, or extraterrestrial terrains.

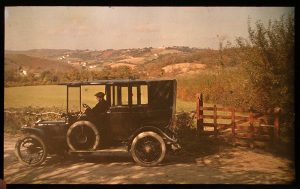

Consider Franklin Price Knott’s ‘Automobile in Italy’ (c. 1910), Hugo Adolf Bernatzik’s ‘Autopanne’, (1927) or NASA’s groundbreaking photographs from the Apollo missions.

Our cultures and societies have developed and been defined by advances in our tools and our means of travel. The modern car came into existence in the late 19th century with the invention of the Benz Patent-Motorwagen.

It didn’t take long for cars to become popular, particularly in the US, where the vehicles and the roads they’re driven on form an essential part of the modern cultural mythos of America. Cars represent an ideal of individual autonomy, freedom and adventurousness. Over the past century, artists have responded to and helped to shape this culture in many ways.

Well-known artists such as Ed Ruscha and Stephen Shore have created distinctive aesthetics from the mundane existence of gas stations, roads, and motorcars.

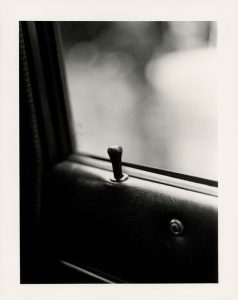

Matt Mullican’s ‘o.T. (Autofensterknopf)’ takes as its subject the recognisable interior of a car, imbuing an everyday detail (a door lock) with the significance of a monolith.

In her piece ‘Feuerwehrhaufen’, Christa Dichgans depicts an absurd heap of fire engines in vivid red. Her drawings of assembled objects are imbued with a Pop sensibility.

David Byrd’s muted tones contrast with Dichgans’ vibrant palette. His large oil painting ‘Woman in Car, Filling Station’ from early 1980s is full of signifiers – the cost of gas per gallon – the exhortation ‘no smokeing’ [sic]. The woman in the car has no eyes. She is viewed through a window – the vehicle appears to be an extension of her body.

Contemporary American artist Billy Al Bengston cites motorcycle culture as a major influence and uses materials from the automotive industry in his work, including spray paint and lacquer applied to sheets of aluminum.

There are just a few examples of the ways in which artists have turned their attention to cars and car culture, exploring the materials, aesthetics and significance of these commonplace and revolutionary machines.

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

Arthur Honegger 'Pacific 231 Mouvement symphonique No.1' Movie 'Asphalt” from 1929

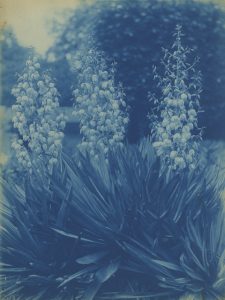

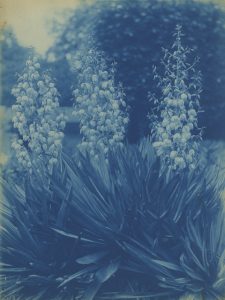

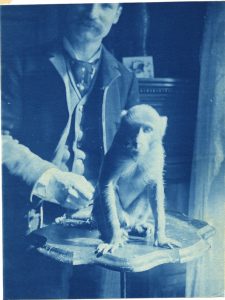

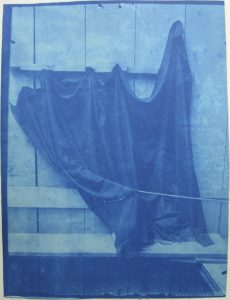

The cyanotype process is chemically simple and limited in terms of the color…

Cyanotype

The English scientist and astronomer Sir John Herschel discovered the cyanotype photographic technique in 1842. The process involves applying a photosensitive solution of potassium ferricyanide and ferric ammonium citrate to a surface such as paper or cloth. A positive image can then be produced by placing a negative (often semi-transparent paper) or objects on the coated surface and exposing it to UV light to create contact prints. These prints are distinguished by their Prussian blue color and durability.Other materials, such as Gold, Silver, Platinum were also used to produce prints of distinctive color.

Alphonse Poitevin was an important inventor in early photographic processes in France. Shortly after discovering the cyanotype process, Herschel introduced it to a British botanist called Anna Atkins who produced a series of cyanotype photograms documenting ferns and other plant life. She is sometimes referred to as the first known female photographer due to this work.

While photographic processes have their own unique history and development, the techniques of photographic image composition have much in common with painting, particularly landscape studies and still life pieces¹ . Elements of the visual languages of perspective and framing are shared across art forms but the darkroom processes of retouching, contact printing, exposure and the fixing of prints are specific to photography.

The cyanotype process is chemically simple and limited in terms of the color, with some variations possible with the use of different sorts of paper, cloth or plates. Like all analogue photography the cyanotype process requires patience and experimentation, as the exposure time traditionally depends on the intensity of sunlight. With today’s technology it’s possible to have more control over the cyanotype process by using a UV-lamp.

Further developments in the cyanotype process allowed rapid and accurate production of copies. This made the cyanotype process useful to engineers and architects – the distinctive white lines on a blue background leading to the term ‘blueprint’ that is still in use today.

¹ Lit: Malin Hylén, Cyanotypes – A New Look at an Old Technique, Central Saint Martin, London 2000

All artwork is available for purchase.

We cannot guarantee the items will still be available upon request.

For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

Other Diversions

Albert Camus - Die Pest Tate Modern UK - Andy Warhol Vatikan Rom - Virtual Tours Louvre Paris - Virtual Tours The Shakespeare Globe Trust Sydney Opera House Münchener Kammerspiele Andrea Bocelli: Music for Hope - Live from Duomo di Milano

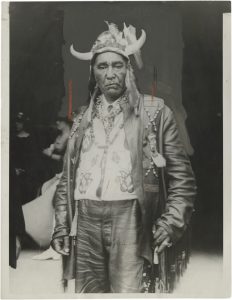

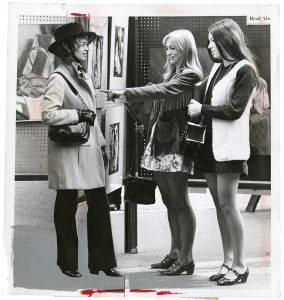

“It is not the camera but the skill of the operator that produces a realistic-looking photograph”

Retouching in Photography

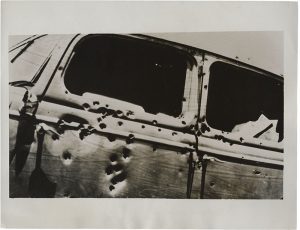

Photographs have been retouched ever since the early days of photography in the 19th century. Over the years, analogue photographers have deployed many darkroom and desk-based techniques as a means of enhancing and manipulating their images. Manual retouching practices include dodging and burning, scratching, airbrushing and marking negatives and prints.

These tangible processes are often visible on vintage press prints, where the skilful hands of photographers and specialist retouchers made notes, painted crop marks and highlighted areas to be reproduced, edited or omitted from the final published images.These highly detailed traces of the creative process are an integral part of analogue photographic history, and are the precursors of many of the digital retouching techniques in common use today.This article presents a short and inevitably incomplete overview of techniques commonly used to modify a photograph during the postproduction process.

Photography has always presented challenges, requiring knowledge of chemical processes, ideal lighting and staging conditions, and the presentation of the final photo in a suitable environment.Essays from the early days of photography in the mid 19th century focus on the question of whether a photograph can ever claim to be a true likeness of reality. The material limitations of lenses and plates often lead to areas of greater darkness or brightness in the image.{1}

Additionally, the framing of the photograph is contingent on the photographer’s intention and decision-making. The image is by its very nature selective.If a photo needed modifications in the mid 19th century it called for manual interventions such as applying powdered pigment, oil paint, watercolour, crayon or pastel. These retouched prints could even easily be mistaken for paintings.{2} This is understandable given the photographers’ backgrounds – French and British photographers around 1850 “were initially trained as painters, draftsmen, or lithographers”.{3}

Photographers such as Louis Daguerre had a scientific background and applied this to discovering new methods of printing and of modifying the plate or the negative directly to get a pleasant result.{4} Early modifications were generally done either to please the portrayed sitter or to compensate for the lack of colour in early black and white photography.{5}

The introduction in the early 1870s of gelatin dry-plate negatives, which could be extensively reworked with soft lead pencils, led to a dramatic increase in the the demand for skilled studio retouchers. {6}Retouching skills continued to be highly valued by both amateurs and professionals in the 20th century.

Photomontage techniques involve making a composite photograph by cutting, gluing and collaging two or more photographs into a new image. Sometimes this new image is photographed to produce a final image.

Photomontage has sometimes been applied as a means of creating false images. Such manipulated photographs can be used politically : “The temptation to ‘rectify’ photographic documents has proved irresistible to modern demagogues of all stripes, from Adolf Hitler to Mao Zedong to Joseph McCarthy.”{7}

In the 1950s and 1960s NY crime photographer Weegee refined some of his pictures to caricatures, apart from some advantageous retouches every now and then on his pictures sent to ACME.{8}

The next big step in the history of photography has been achieved by the advent of digital technologies. Now the previously manual processes of retouching are often done on a screen, using a tool named Photoshop.

[1] In an article titled “Photography and Authority”, published in 1864 in the inaugural volume of the Philadelphia Photographer, the Reverend H.J. Morton attributed to the medium a kind of clear-sighted, divine omniscience. The camera, he maintained, “sees everything, and it represents just what it sees. It has an eye that cannot be deceived, and a fidelity that cannot be corrupted“ (in Fineman, footnote 20, H.J. Morton “Photography as an Authority” in: The Philadelphia Photographer 1, no 12, Dec1864, p. 180 [2] Mia Fineman, Faking it. Manipulated Photography before Photoshop, 2012 Metropolitain Museum NY, p. 9 [3] Fineman, p. 45 [4] The optimal solution was to print a landscape from two negatives, one exposed for the land, the other for the sky.(..) At a time when the camera exposures often lasted for several seconds, viewers were amazed by Le Gray’s ability to freeze the motion of breaking waves, and the perfectly backlit clouds drifting above reinforced the feeling of instantaneity. That the clouds and the waves were printed from two separate negatives remained the artist’s secret during lifetime. Fineman, p. 47f. [5] The desire for greater optical realism has by no means been the only motivation for manipulating photographic images. Fineman, p. 15 [6] Fineman, p. 63 [7] Fineman, p. 91 [8] Eg “Draft Johnson for President”, c. 1968

All artwork is available for purchase.

We cannot guarantee the items will still be available upon request.

For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

Other Diversions

Robert Flaherty - Nanook of the North (1922) Staatsoper TV: Oper und Ballett im kostenlosen Live-Stream Royal Opera House The Metropolitan Opera - Nightly Opera Streams Kosmos Heartfield Musee Unterlinden Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz British Museum - African Rock Art Courthard Institute of Art Robert Flaherty - Moana 1926 F.W. Murnau - Tabu: A story of the South Sea, 1931

+49 89 29 73 42

+49 89 29 73 42