Month: October 2020

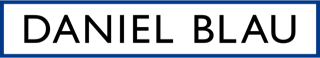

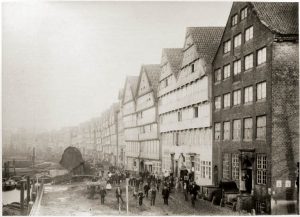

Georg Koppmann (1842 – 1909) | Historic Hamburg

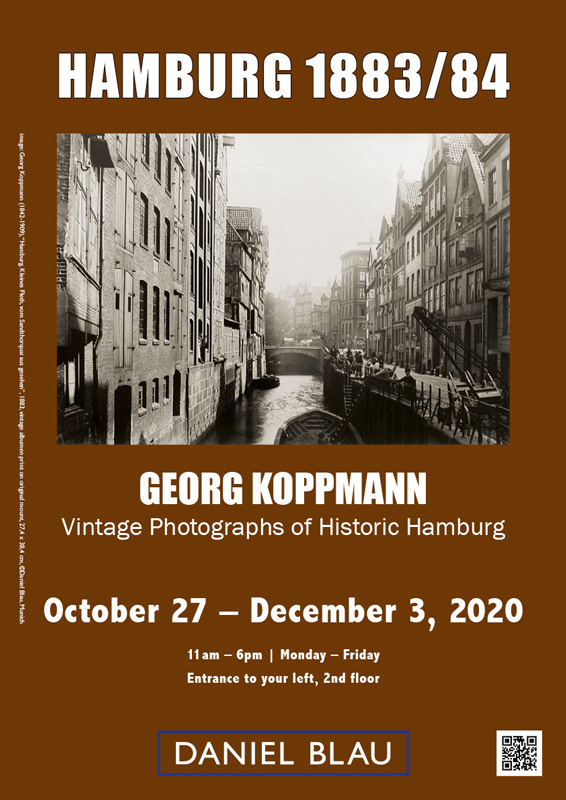

DANIEL BLAU is pleased to present an exhibition of vintage photographs showing historic sites of Hamburg in 1883/84. These photographs were taken by Georg Koppmann shortly before the demolition of the sites ahead of the construction of the Speicherstadt.

Exhibition:

October 27 – December 3, 2020

11am – 6pm | mon – fri

Maximilianstraße 26, 80539 München

Set of 30 photographs; 17 on display

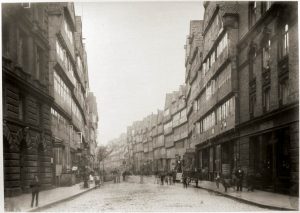

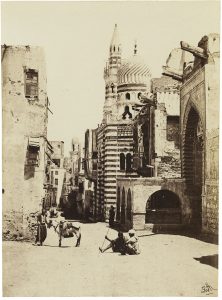

Francis Frith’s (1822-1898) photographic tours to Egypt in 1856-57 and 1859-60 were by far

the most ambitious and systematic excursions of his time

A Victorian Photographer Abroad

The Photographic Voyage of Francis Frith to Egypt

“Following my bent toward the romantic and perfected past, rather than to the bustling and immature present, I went East. … I would begin at the beginning of human history: I would track the Sun back to rising, and see the lands upon which his first beams fell. … It would, of course, be easy to fill my book with details of these bewitching wanderings, the memories of which are worth, to me, moutains of gold and silver.”

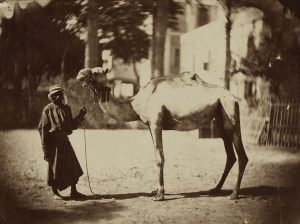

Francis Frith’s (1822-1898) photographic tours to Egypt in 1856-57 and 1859-60 were by far the most ambitious and systematic excursions of his time. By the time he left Liverpool for Egypt, Frith was already a recognized photographer.

His first experiments with photography are to be dated between 1851, when Frederick Scott Archer’s wet-collodion process was made generally available, and 1853, when Frith is recorded as a founding member of the Liverpool Photographic Society. Only a few years of practical photographic exercise later, he set out on his first Egyptian journey. The expedition was thoroughly planned, costly, elaborately outfitted, and conducted at a leisurley pace. Frith brought with him his stereo, the whole-plate and his mammoth-plate cameras, of which the latter was situated inside a covered vehicle which also functioned as portable darkroom and as a shelter. “We did not,” Frith wrote, “anticipate much in the way of successful results, for, as far as we were aware, we were the first to carry the process into hot countries.” At this time, the wet-plate process was still untested in desert conditions. The climate made the photographer creative, “Many of my photographic pictures were made in tombs! to save myself the trouble of pitching my dark tent, and also for the sake of their greater coolness, I very often availed myself of a rock-tomb.”

“Notwithstanding all that I had read and imagined, I was not in the least prepared for the extraordinary and brilliant novelty of the scene that burst upon my eye on first landing in an Eastern port. … Alexandria was the greatest ‘sensation’ that I had ever experienced.”

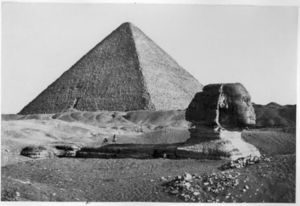

Over the course of the group’s months-long tour, Frith photographed sites throughout Upper Egypt, including Aswan, Gebel el-Silsila, Edfu, Armant, and the Cataracts of the Nile. However, the majority of his subjects were found in the vicinity of Thebes, Luxor, and Karnak, before travel continued on to Cairo and the Great Pyramids. By then the summer season was approaching, and the climate was growing inhospitable. In July 1857, Frith returned to England, carrying with him his first set of negatives, ready for printing and exhibition.

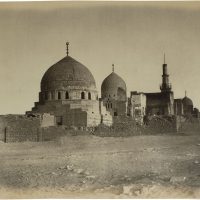

The second voyage began that November, with Mediterranean temperatures now subsiding. Together again with the other travellers, the trip back to Cairo was made by steamship, and Frith started his photographic work anew on Islamic mosques, tombs, and Cairo street scenes. Frith probably spent the winter in Egypt before traveling to Jaffa sometime in early 1858, where the group spent more than a year. In July 1859 they “spent a summer in Cairo and its neighborhood, sweltering in an occasional heat of 108° to 110° Fahrenheit all through the night.” The new series of negatives continued with subjects like mosques, cemeteries, the Citadel, street views, flora and fauna, the pyramids, the Sphinx, the tombs at Sakkara and Dahshur, the pyramids at Giza, the stone quarries of Tura, and the Temple of Kalabsha.

With his departure for the voyage home in the early summer of 1860, Frith left behind what he considered his last “grand spell of sunshine” and readied himself for the responsibilities of marriage and business that awaited him in England.

source: Douglas R. Nickel, “Francis Frith in Egypt and Palestine. A Victorian Photographer Abroad”, Princeton University Press Princeton, New Jersey/Woodstock, Oxfordshire 2004.

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

Autochromes and the Lumière brothers EMOP Berlin Helmut Newton Foundation

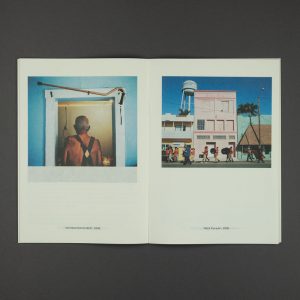

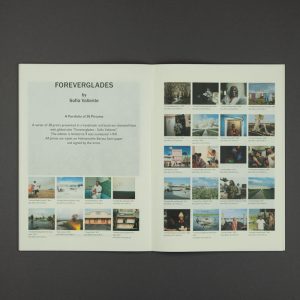

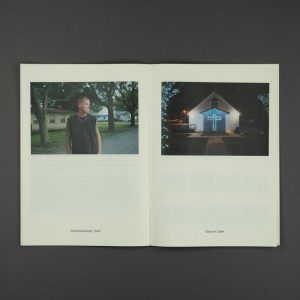

Foreverglades & Miracle Village

Foreverglades & Miracle Village by Sofia Valiente

For decades after Western Expansion, South Florida was still a wilderness.

Only once pioneers dredged canals and redirected the flow of Lake

Okeechobee did this area become habitable. These once considered “useless”

territories of marshes and swamps ultimately gave way to development and

industry.

On the southern tip of the lake lies Belle Glade, a small agricultural town that

one might pass on a road trip today, just a couple of stoplights and it’s gone. It

hides a rich history that leads to how we arrived here in Florida.

In 2015, I moved into a former rooming house apartment in Belle Glade

and soon after came across books by Lawrence E. Will and Zora Neale

Hurston. Will painted a picture of the pioneers who developed the area

through persistence and foresight, and for me, Hurston gave a voice to the

workers who built the Glades with their bare hands. Their writing became my

framework for exploring the past and looking at its contemporary parallels. In

this time capsule, history is present — roots run deep and the pioneer spirit

can still be felt.

As a photographer and storyteller, I have frequently sought to understand

how deep the “iceberg” reaches. For my first published work, “Miracle

Village”, which documents the lives of sex offenders living together in a

community, my pursuit focused on the events leading up to each person’s

convictions and the psychology of a person who lives as a modern-day leper.

With my latest project, “Foreverglades”, I looked to history as a framework

for understanding how American capitalism has shaped and continues to

reshape, our communities. I studied how this pioneer spirit was built on

tenacity and doggedness. I see humanity as a collective whose individual

people play differing roles and whose stories are interwoven in a deep

tapestry. For me, the present is a question that history answers.

My intention with constructing a steamboat replica was to reproduce an

artifact that was very specific to a time period when all travel was done

by boat. I grew up in the suburbs an hour away from this region, where

development has homogenized the urban landscape and where history has

been paved over. I wanted to create this juxtaposition between the artifact

and the modern cities on the coast.

I believe it is important to make work available to audiences who don’t

normally consume documentary photos and storytelling. Meeting people

where they are is inclusive of a larger audience. With Foreverglades, I

personally spent three months at the exhibit educating the people who

came to visit. It was an incredible gamut of people, from scientists to people

interested in everything from art to history, to residents who happened to

stumble upon it — all political parties, ethnicities, and ages.

Sofia Valiente, 2020

Printed and bound by Pelo-Druck Lohner oHG

Paper content: Offset 50g/m2

Paper cover: Olin, Rough, cream, 200g/m2

Published: 2020

36 pages, 22 images

15×21 cm, softcover

ISBN: 978-3-9821983-1-6

Editor: Daniel Blau

Grapes Lost and Found

Grapes Lost and Found

In a recent conversation I had with Billy Al Bengston, he quoted his racing buddy:

“If it only costs money, it’s cheap.” Being an avid collector myself (although not of

Contemporary Art) my interpretation of his words is: It can take a lot of effort, time

and money to track down a specific object. Sometimes it can take years and money can’t

help.

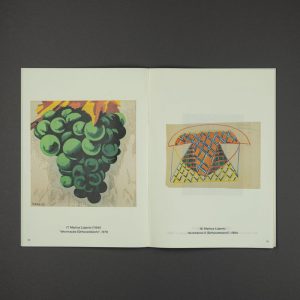

We had an exhibition of large Lüpertz paintings from 1967-70 at Art Basel in 2005.

The paintings were huge. The show looked stunning and was a great success. The

painting “Weintrauben” did not find a place in the show of tree trunks, telegraph

poles and tunnels and remained upstairs in storage to return with the other works

to Germany after the fair. But it never arrived. We only realized it had gone missing

about a year later when a loan request for the work came and we couldn’t locate it.

Now, 15 years later, a friend sends me this cryptic text message: “Dear Daniel, tell

me, are you missing a grape painting? I hope you are well. Best wishes…”

It turns out that the crate, with our label still on it, mysteriously turned up in a

private furniture warehouse in Munich. The owner of that warehouse is a friend of

our friend. I thought “Great! The grapes are back.” But then the finder emailed:

“How can I be sure you are the owner? I think I’d better go to the police.” Days

of silence followed. The painting had vanished again. Then somebody within the

city’s Lost and Found department called up. He had been referred to us by the

Lenbachhaus, and wondered if we dealt in Lüpertz. “There is this painting someone

found…”

I am sure that many of the artworks we enjoy today would have fascinating stories

to tell, if only they could speak to us in words as well as with their beauty.

I thought this lucky moment merited a presentation on the theme of flora and

color.

Karl-Heinz Schwind was our first exhibition when we opened some 30 years ago.

His works are pure energy.

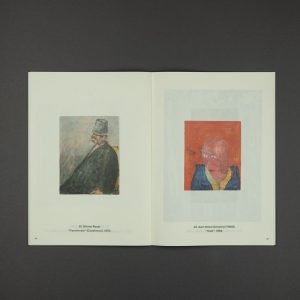

Eugène Leroy, who sometimes worked for several years on a painting before

considering it finished, Don van Vliet, painter and cult musician known as Captain

Beefheart and Billy Al Bengston, known for his tropical themes and vivid colors,

are well known and do not need my introduction.

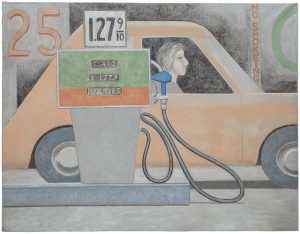

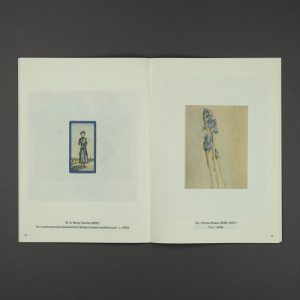

David Byrd is neither “Insider” nor “Outsider”. Having studied art after WWII

under Amédée Ozenfant, he only developed his mature style and produced his

most defining body of work after he started working as an orderly at a hospital

psychiatric ward, from 1958-88. His paintings defy any of the “Isms” we usually like

to apply to art we see; they stand apart from Pop, Realism or Expressionism.

If anything I would refer to his work as “New York Surrealism”. Byrd’s works have

an airy and somewhat aetherial quality, as if viewed through a milky glass.

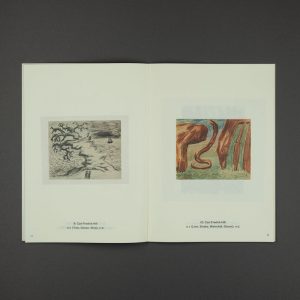

C.F. Hill, on the other hand, is what one could call an “artist’s artist” – he is known

to art enthusiasts outside of his home country of Sweden who are interested

in the origins of what we call “Modern Art”. He began as an academic painter,

living for some years in France before a serious nervous breakdown brought him

back to Sweden where he was hospitalized for 5 years. He radically changed his

style and thenceforth his hallucinations and persecution mania inspired his work.

Mostly working on paper with pencil, colored pencil, charcoal or pastel, he created

mysterious landscapes reminding me of the prints done several hundred years

earlier by Hercules Seghers, landscapes out of fairy tales or nightmares.

Guerle and Nény were true self-taught artists who remained more or less in

obscurity but whose visual languages are equally inspiring and distinctive as the

better-known artists in our exhibition. They only came to my attention through

writers like Hans Prinzhorn or Dr. Jean Lacassagne, who were interested in and

propagated the artistic output of mentally insane or criminal individuals. Prinzhorn’s

Bildnerei der Geisteskranken (Berlin 1922) and Albums du Crocodile by Lacassagne

(Lyon 1939) have been rare sources of information on these fascinating artists.

D.B., 2020

Printed and bound by Pelo-Druck Lohner oHG

Paper content: Offset 50g/m2

Paper cover: Olin, Rough, cream, 200g/m2

38 pages, 26 images

15×21 cm, softcover

Editor: Daniel Blau

“Travel to Egypt? They all start dancing with sheer joy,” he wrote.

“As if that was something other than going to London.”

Traveling Photographers

Photography from The Travel Bug of the Nineteenth Century

In 1824, Eugène Delacroix was still critical of the newly emerging interest in travel to the Middle East, “Travel to Egypt? They all start dancing with sheer joy,” he wrote. “As if that was something other than going to London.” Only a few years later, in January 1832, Delacroix left France to journey to the African coast himself, in support of Charles Henri Edgar, Count of Mornay’s diplomatic delegation to Sultan Abd al-Rahman. The delegation was mandated by the government of King Louis Philippe to start a dialogue concerning the political events of adjacent Algeria. The vague political situation in the nineteenth century required numerous diplomatic missions, which were often accompanied by artists or photographers. Thanks to these contemporary witnesses – solo travelers as well as documenting escorts – the western world learned about the countries of the Far and Middle East. However, not only the artworld profited from these long-distance travels. Steamboat and railway reduced travel time and offered a new degree of comfort and luxury. Shipping lines like the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Company were established as a regular link between England and Egypt. From 1883 the Orient Express ran on the route from Paris to Constantinople. Travel agencies like Thomas Cook recognized the trend and acted accordingly by offering guided journeys to the Orient.

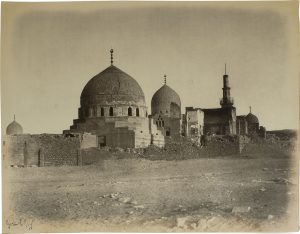

Gustave le Gray (1820-1884) is considered the most important and influential photographer of the second half of the nineteenth century. His photographs are so rare and highly collectable that many have set record auction prices. Le Gray studied painting with Paul Delaroche. His interest turned to chemistry and photography and by 1855 he had won the high accolade of the “Medaille de Première Classe” at the Universal Exhibition.

Maxime Du Camp (1822-1894) took photography lessons from Gustave le Gray and travelled in 1849 with Gustave Flaubert to Egypt. His journals and subsequent books, such as Le Nil (1855), along with Flaubert’s letters and travel notes, provide one of the most complete accounts of the European experience of Middle Eastern travel and of the daunting enterprise of making photographs during the early years of photography.

Francis Frith (1822-1898) was the most well-known nineteenth-century photographer who travelled to the Middle East. On two of his three excursions to the Middle East he visited Egypt, first in 1856-57 and later in 1859-60

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

Robinson Crusoe, Tom Sawyer & Huckleberry Finn, Treasure Island and Moby Dick Museum Fünf Kontinente - Database Photography online Music for Wanderlust

+49 89 29 73 42

+49 89 29 73 42