Month: February 2021

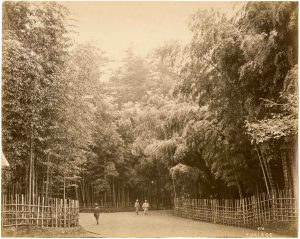

Photography was first introduced to Japan at a time of great upheaval in the country.

Early Photography in Japan

Fundamental political, social, and economic convulsions were followed by rapid reform and modernization. In the midst of it all, early photographers, both western and Japanese, were able to capture the people, places, and events of a changing world on camera.

The story of photography’s spread throughout Japan begins on the southern island of Kyūshū. During the Edo period (1615-1868), Kyūshū’s dominant clans obtained information regarding the outside world from Nagasaki, via the small Dutch trading outpost on the artificial island of Dejima. It was through Dejima that photography was first introduced to Japan. Since literature regarding early photography – and teachers, necessarily foreign, of the new craft – were scarce, early enthusiasts had to rely on personal encounters with foreign professionals to acquire photographic skills and knowledge of their own.

It was around 1846 when the daguerreotype camera, using silver plates, was first brought to Japan. One such apparatus was brought from Dejima to the Takeo clan by a merchant named Ueno Shunnojō, whose son, Hikoma, would go on to become an accomplished photographer in his own right. The Takeo clan returned the daguerreotype to the Dutch, however, unable to understand how to use it. It was only after that that some of Dejima’s own residents, notably doctors like Van den Broek and his successor Pompe, along with their Japanese medical students, attempted to learn the art themselves, aided by little more than Dutch books and manuals. At the same time, the Satsuma and Fukuoka clans also began tackling the secrets of the photographic process. Each clan had achieved partial success with silver plates by the latter half of the 1850s; for this reason, those few years can be seen as the true dawn of photography in Japan.

Today, 75 years later, the photographs taken in Nagasaki on August 10, 1945, are considered the most extensive eyewitness account of the bombing, and the “ground zero” of Atomic Photography.

The encounters between the French photographer P. Rossier and early Japanese pioneers of photography, such as Furukawa Shunpei, Maeda Genzō, and Ueno Hikoma, brought about further developments, in leaps and bounds, in Japanese photography. Rossier came to Nagasaki as a correspondent, and subsequently became the first photographer to sell landscape photographs of Japan in Europe.

When Felice Beato (1834 – c. 1900) established a photographic studio in Yokohama in 1863, he was at the height of his creativity. At this point Beato had already built up an impressive track record as a commercial photographer, having chronicled the Crimean War, the Indian Mutiny and the Second Opium War in China. Beato was therefore unique among his western contemporaries in Japan for his photographic experience. During the remainder of the 1860s, and well into the following decade, Beato enjoyed a reputation as the country’s premier photographer, until he sold his studio to Baron von Stillfried in 1877. Beato’s work remains the first significant body of photographs taken by a western photographer living and working in Japan, one with which both Japanese and westerners were familiar. The history of photography – not only in Japan, but also as a worldwide whole – is richer as a result of his life, his work, and the artistic encounter it engendered.

Hand-Colored Photographs

Throughout the nineteenth century, photography was entirely black and white. While differences in shading might be discernable from one print to another, depending on the exact process used to produce them, the data captured by cameras themselves was monochromatic. This was because silver halides – the family of salts that are light-sensitive enough for use in cameras – only respond to light at the blue end of the visual spectrum, which made recording colors in other parts of the spectrum difficult. There already existed a long history of hand-coloring etchings and engravings, though, and this practice was easily transferred to the new medium of the photograph.

The daguerreotype in its earliest form had a dull, gray appearance, which was often relieved by applying pale red highlights to the subject’s cheeks or spots of gold to the buttons on a jacket.

In Japan, albumen prints (produced for the tourist trade) were often treated with wild applications of color – cherry blossoms became pink, hanging wisteria blue. These modifications were made with diluted oil paints prepared for the purpose. Even long after the invention of color photography these oil colors were still sold in kits, so that the favorite family portrait could be customized and made more lifelike.

Sources:

Terry Bennett, “Photography in Japan. 1853-1912”, Singapore 2006.

Nicole Coolidge Rousmaniere, Mikiko Hirayama, “Reflecting Truth. Japanese Photography in the Nineteenth Century”, Amsterdam 2004.

Richard Benson, “The Printed Picture”, published by the Museum of Modern Art, New York 2008, p. 186.

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

How Colorized Photos Helped Introduce Japan to the World Tourism and Science in Early Japanese Photographs Sites of 'Disconnectedness': The Port City of Yokohama, Souvenir Photography, and its Audience Digital Photo Colorization The Paper Time Machine Cees Nooteboom Explores the Ancient Japanese Temple Kozan-ji Sam Francis in Japan by Richard Speer

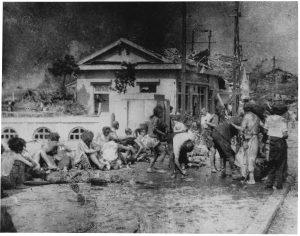

Eyewitnesses of the final bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Yoshito Matsushige

Yoshito Matsushige (1913-2005) was born in Kure, Hiroshima. As a photojournalist, he took five photographs on August 6, 1945, the day of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. At the time of the explosion, Matsushige was at home, 2.7 km south of the hypocentre. He is the only person to have captured an immediate, first-hand photographic account of the bombing. Matsushige dedicated most of the rest of his life to organizing and preserving the photographic history of the atomic bombing of his hometown.

“I had finished breakfast and was getting ready to go to the newspaper when it happened. There was a flash from the indoor wires as if lightening had struck. I didn’t hear any sound, how shall I say, the world around me turned bright white. And I was momentarily blinded as if a magnesium light had lit up in front of my eyes. Immediately after that, the blast came. I was bare from the waist up, and the blast was so intense, it felt like hundreds of needles were stabling me all at once. The blast grew large holes in the walls of the first and second floor. I could barely see the room because of all the dirt. I pulled my camera and the clothes issued by the military headquarters out from under the mound of the debris, and I got dressed. I thought I would go to either the newspaper or to the headquarters. That was about 40 minutes after the blast. Near the Miyuki Bridge, there was a police box. Most of the victims who had gathered there were junior high school girls from the Hiroshima Girls Business School and the Hiroshima Junior High School No.1. They had been mobilized to evacuate buildings and were outside when the bomb fell. Having been directly exposed to the heat rays, they were covered with blisters, the size of balls, on their backs, their faces, their shoulders and their arms. The blisters were starting to burst open and their skin hung down like rugs. Some of the children even have burns on the soles of their feet. They’d lost their shoes and run barefoot through the burning fire. When I saw this, I thought I would take a picture and I picked up my camera. But I couldn’t push the shutter because the sight was so pathetic. Even though I too was a victim of the same bomb, I only had minor injuries from glass fragments, whereas these people were dying. It was such a cruel sight that I couldn’t bring myself to press the shutter. Perhaps I hesitated there for about 20 minutes, but I finally summoned up the courage to take one picture. Then, I moved 4 or 5 meters forward to take the second picture. Even today, I clearly remember how the view finder was clouded over with my tears. I felt that everyone was looking at me and thinking angrily, “He’s taking our picture and will bring us no help at all.” Still, I had to press the shutter, so I harden my heart and finally I took the second shot. Those people must have thought me duly cold-hearted. Then, I saw a burnt streetcar which had just turned the corner at Kamiya-cho. There were passengers still in the car. I put my foot onto the steps of the car and I looked inside. There were perhaps 15 or 16 people in front of the car. They laid dead one on top of another. Kamiya-cho was very close to the hypocenter, about 200 meters away. The passengers had stripped them of all their clothes. They say that when you are terrified, you tremble and your hair stands on end. And I felt just this tremble when I saw this scene. I stepped down to take a picture and I put my hand on my camera. But I felt so sorry for these dead and naked people whose photo would be left to posterity that I couldn’t take the shot. Also, in those days we weren’t allowed to publish the photographs of corpses in the newspapers. After that, I walked around, I walked through the section of town which had been hit hardest. I walked for close to three hours. But I couldn’t take even one picture of that central area. There were other cameramen in the army shipping group and also at the newspaper as well. But the fact that not a single one of them was able to take pictures seems to indicate just how brutal the bombing actually was. I don’t pride myself on it, but it’s a small consolation that I was able to take at least five pictures. During the war, air-raids took place practically every night. And after the war began, there were many foods shortages. Those of us who experienced all these hardships, we hope that such suffering will never be experienced again by our children and our grandchildren. Not only our children and grandchildren, but all future generations should not have to go through this tragedy. That is why I want young people to listen to our testimonies and to choose the right path, the path which leads to peace.”

Yosuke Yamahata

At the time of the final bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, in August 1945, Yōsuke Yamahata (1917-1966) was a propaganda photographer for the Japanese News and Navy Divisions of the Information Bureau. Yamahata spent most of the 1940s in Southeast Asia, where he photographed the deployment of the Japanese military. When the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima he was 28, and just transferred back to Tokyo. He had driven through Hiroshima the previous day, on his way to the military base In Hakata. Three days later Nagasaki was bombed. An investigative team left Hakata for Nagasaki, or what remained of it, that same evening. It consisted of Yamahata, the writer Jun Higashi, the painter Eiji Yamada, and two military escorts. It was night the next day when they returned, and when Yamahata, gone immediately to develop his film alone in his darkroom, made the decision to keep it, not to turn it over to the News and Information Bureau. It wasn’t until the end of the month – after Japan had surrendered, and with encouragement from his father – that Yamahata published the first of his pictures, in daily newspapers distributed nationwide. Soon afterwards the new press censorship orders from General MacArthur, now Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, took effect, and banned any publication in connection with nuclear warfare for the next seven years. It was 1952 before censorship was lifted again and Yamahata’s photographs were made available to the public, in a monograph entitled Atomized Nagasaki. For the photographer, the following years were characterized by the push and pull of his pictures’ use, or misuse, as military propaganda, and their place in the struggle for nuclear disarmament and world peace.

Today, 75 years later, the photographs taken in Nagasaki on August 10, 1945, are considered the most extensive eyewitness account of the bombing, and the “ground zero” of Atomic Photography.

Publication “X-Ray Japan -1945” Get Your Copy Here

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

Yoshito Matsushige's video testimony by Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum Documentary 'Tale of Two Cities' Document by U.S. Army Signal Corpse Pictorial Division 'The Atom Strikes!'

This collection brings together 47 of Alphonse Poitevin’s vintage prints, offering a unique and exclusive insight into his life’s work, and hoping thereby to spur new interest and further research into his extraordinary alchemist.

84 pages, 97 illustrations, with essays by Martin Jürgens and Katharina Rohmeder

18,5 × 25,5 cm, softcover,

published by:

Hirmer Publishers, 2021

Printed and bound by:

Pelo-Druck Lohner OHG

paper content: Tauro 120g/m

paper cober: Gardamatt Art 350g/m

Edition: 750

€ 20 plus shipping

ISBN: 978-3-7774-3747-7

Order your copy exclusivly here: contact@danielblau.com

Purchase your copy here

3 under 30

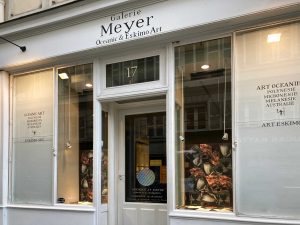

Daniel Blau is pleased to show the three winners of 3 Under 30, the gallery’s competition for young photographers, at Galerie Meyer in Paris.

Galerie Meyer

17, rue des Beaux Arts

75006 Paris

VIP Opening:

Thursday, January 7, 2021

11 am – 7pm

Public Exhibition:

January 7 – 23, 2021 !! extended until January 30th, 2021 !!

Opening Hours:

Tuesday to Friday

2.30 pm – 6 pm

Saturday

11 am – 1 pm,

2.30 pm – 7 pm

Please Respect the Health Precautions and Social Distancing

Galerie Meyer reserves the right to limit the occupancy in accordance with Government Health Regulations

+49 89 29 73 42

+49 89 29 73 42