Month: April 2021

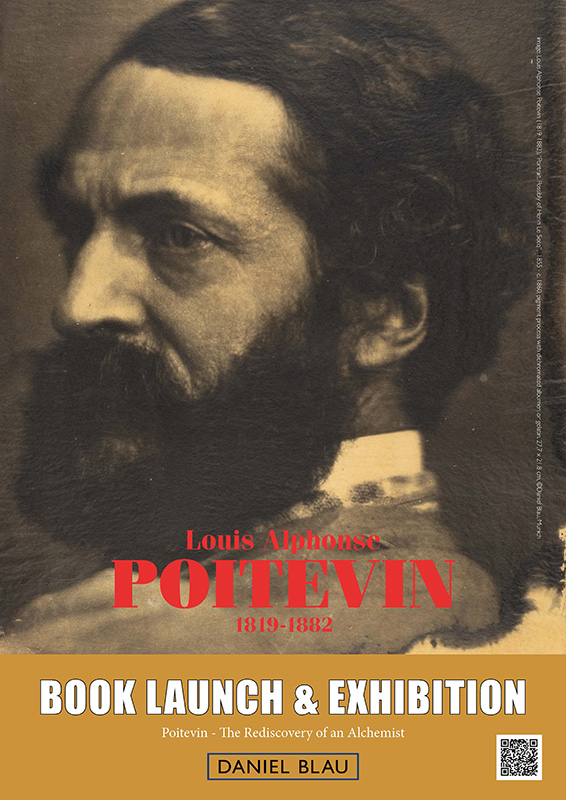

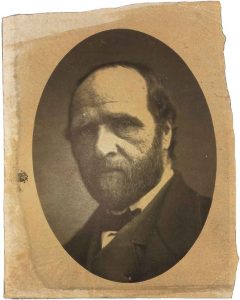

Louis Alphonse Poitevin

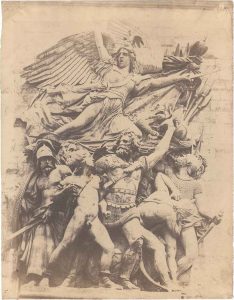

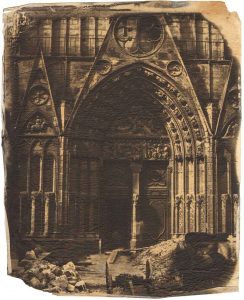

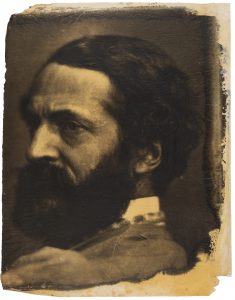

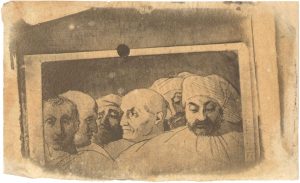

DANIEL BLAU is pleased to present Louis Alphonse Poitevin, an exhibition honoring an outstanding inventor, chemist, engineer, researcher, artist and photographer, and one of the most important characters in the development of photography as we know it today.

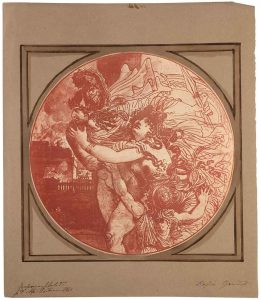

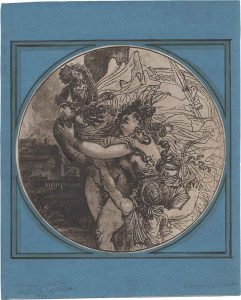

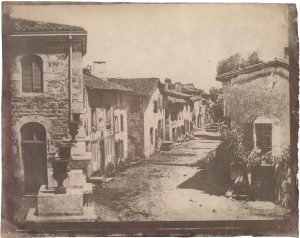

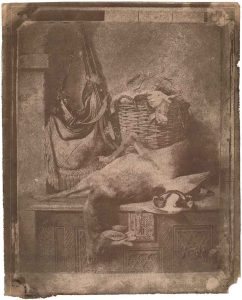

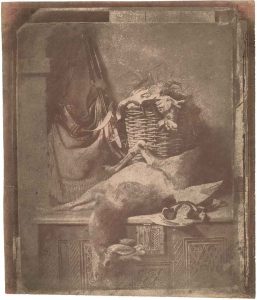

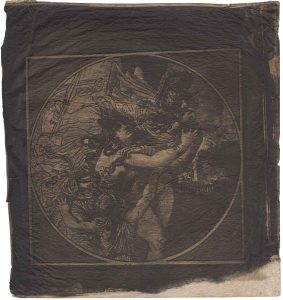

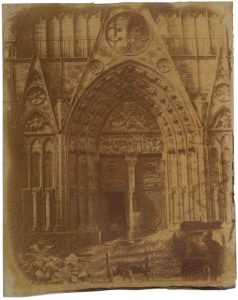

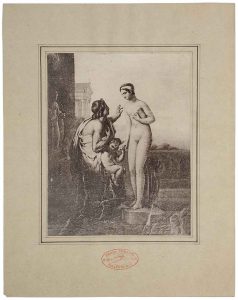

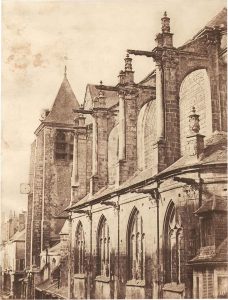

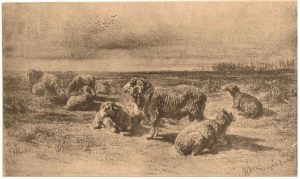

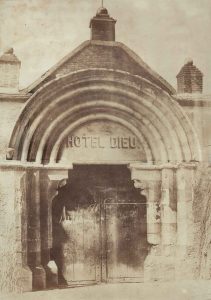

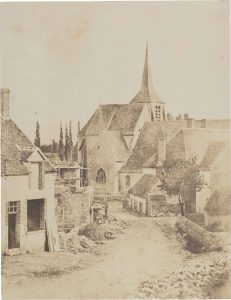

For more than 35 years, Louis Alphonse Poitevin (1819-1882) experimented with chemical and mechanical processes in search of a printable and longer-lasting photograph. He recognized early on that photography had the potential to revolutionize how mass-produced books were illustrated. His work brought that revolution about, creating the first practical process for printing photographs, as illustrations within books, on an industrial scale.

This exhibition of Alphonse Poitevin’s work, featuring 47 rare photographs, offers the opportunity for an in-depth view into some of his most prescient inventions. Poitevin is remembered today most for establishing the fundamental principles of four non-silver process families: photolithography, collotype, dichromate relief systems, and the carbon pigment process.

Exhibition: until July 20th, 2021 | paused until July 16th for a special exhibition

11am – 6pm | mon – fri

Maximilianstraße 26, 80539 München

All artworks are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

Louis Alphonse Poitevin (1819-1882)

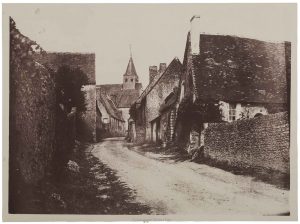

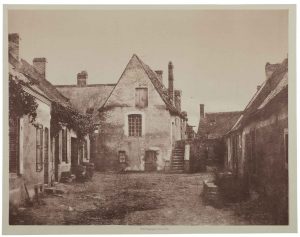

Louis Alphonse Poitevin was born in the small town of Conflans-sur-Anille, halfway between Paris and Nantes, on August 30, 1819. After graduating from school in 1838, he moved to Paris to study chemistry at the École Centrale des Arts et Manufacture. In 1839, the discovery of the daguerreotype was announced at the Académie des sciences, and Poitevin became immediately hooked on photography. He purchased a camera and the necessary utensils for this new art and began making daguerreotypes in his free time.

Poitevin left the École Centrale just as France was entering the era of industrialisation, and from 1844 on he was quickly able to find employment as a chemical engineer. Over the next 30 years, he worked in salt and copper mines and glassware factories all over France and even in Algeria. At these locations, and in bouts between assignments, he dedicated his spare time to the study and invention of new photographic processes, in a constant quest for improving working practices and achieving successful results, an approach he also applied to his professional engineering tasks. He was extremely versatile in his projects, inventing both photomechanical and photochemical processes. The former include early methods of converting daguerreotype images into printing matrixes, the first successful photolithographic process, and explorations into the fundamentals of the later invented collotype. The latter combined both positives and negatives, on paper, glass, and even ceramics.

With his photolithographic technique of 1855, Poitevin won the much sought after Grand prix du Duc de Luynes in 1867, a contest run by the Societé française de photographie designed to stimulate research into developing a photomechanical process for the photographic illustration of publications. He also won a number of prizes for his non-silver photographic techniques, including a gold medal at the International Exposition in Paris in 1878. He held five patents, and his book “Traité des impressions photographiques” was published twice: the first edition in 1862 and a posthumous second edition in 1883. He published over 80 technical articles in professional journals of photography and printing. Poitevin died on March 4, 1882, in the village of his birth, leaving behind his wife Sophie (née Pequegnot), whom he had married in 1865.

Text by: Martin Jürgens, 2021

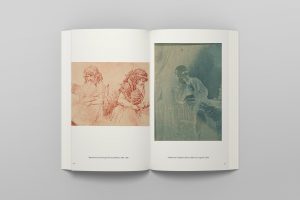

See recent publication “Louis Alphonse Poitevin”

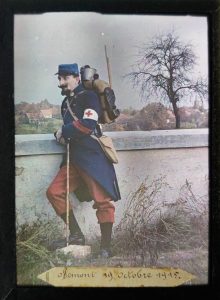

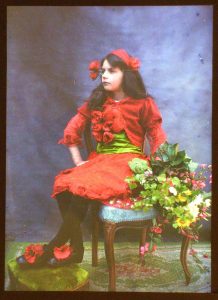

Auguste (1862-1954) and Louis (1864-1948) Lumière

The Lumière Autochrome, invented by Auguste (1862-1954) and Louis (1864-1948) Lumière, was the first practical and commercially viable process of color photography. After ten years of research and experimentation, the Lumière firm introduced the first Autochrome plate to the world in 1907. The Brothers Lumière were also the inventors of the Cinémathographe, patented on February 13, 1895. France’s first public film screening, in front of a paying audience, took place on December 28 of the same year.

Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946)

Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946) was more than just a photographer: an enormously influential gallerist, he introduced the European avant-garde and their works to the world of contemporary American art. In 1903 he founded the annual magazine Camera Work, which contained critiques and reproductions of avant-garde artists alongside photographs. Matisse, Cézanne, Rodin, and Braque, among others, all exhibited at Galerie 291, founded by Stieglitz and Edward Steichen in 1905.

Ellis Kelsey (1866-1939)

Ellis Kelsey (1866-1939), who had been moonlighting as a photographer since 1889, turned to the Lumière Autochrome as soon as it was released, in 1907. By 1908 he was already able to show eight pieces, his first color photographic work, in exhibition at the Royal Photographic Society in London.

Samuel Gottscho (1875-1971)

The photographs of Samuel Gottscho (1875-1971) expose a particular fondness for architecture, landscape, nature, and countryside living. Despite dabbling in the art since 1896, it was only at the age of fifty that his hobby became a career. His photographs appeared in the pages – and even graced the covers – of American Architect and Architecture, Architectural Record, The New York Times, not to mention numerous home decoration magazines.

Louis Alphonse Poitevin

Poitevin – The Rediscovery of an Alchemist

Daniel Blau is pleased to present Louis Alphonse Poitevin: outstanding inventor, chemist,

engineer, researcher, artist and photographer.

For more than 35 years Poitevin (1819-1882) experimented with chemical and mechanical processes to make photographic images printable and durable. Poitevin recognized early on

how important photography would be to illustrate printed books. He developed the first applicable methods, the implementation of which made the printing of photographically

illustrated books possible in the first place. Presenting 47 rare photographs, this exhibition of Alphonse Poitevin’s work offers the opportunity for an in-depth view into some of his most prescient inventions in photography.

Poitevin is remembered today most for establishing the fundamental principles of four nonsilver process families: photolithography, collotype, dichromate relief systems, and the carbon pigment process. His inventions refined existing techniques and made the mechanical reproduction of images and thus, the illustration of printed books, possible.

The publication offers the unique opportunity to take a comprehensive look at the life and work of the famous pioneer of photography using a large number of different photographs

and the latest cutting-edge-technology research results. The volume brings together photographs and the results of experiments that provide a comprehensive insight into Poitevin’s work and place his achievements in both a technical and an art-historical context.

Alphonse Poitevin here at last receives some of the attention he deserves.

Available to order!

Editor:

Daniel Blau

Maximilianstr. 26

80539 Munich

Published by:

Hirmer Publishers

Bayerstr. 57-59

80335 Munich

Printed and bound by Pelo-Druck Lohner oHG

Paper content: Tauro 120 g/m2

Paper cover: Flexcover, Gardamatt 350g/m2

84 pages, 97 illustrations

25,0×18,5cm, softcover

ISBN: 978-3-7774-3747-7

€ 29,90

Published: 2021

Copyright: all illustrations © Daniel Blau, Munich

Text: Martin Jürgens, Katharina Rohmeder

Layout: Christiane Wunsch

Editor: Robert Isaf

Order your copy exclusivly here: contact@danielblau.com

or via Hirmer Publishers

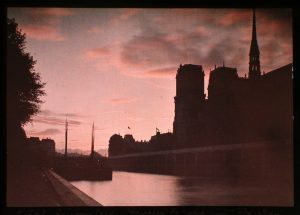

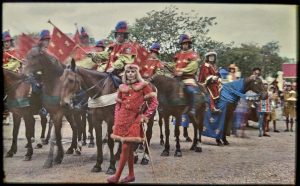

The Lumière Autochrome, invented and marketed by brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière,

was the world’s first practical color photography process.

The Art of the Autochrome

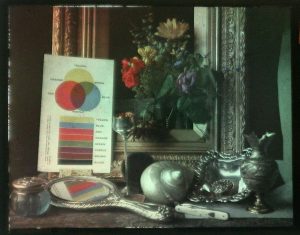

Even from the moment of photography’s invention, the absence of color was recognized as one of its greatest shortcomings. The development of color photography became one of photomechanical research’s primary goals over the course of the 19th century. The photosensitive material in use at the time did in fact register the wavelengths of different colors in our visible spectrum when recording an image – there simply wasn’t a way to directly reproduce that color. Once it was understood that a simple re-creation of color wouldn’t be possible, the technical pioneers and inventors of the time searched for another method, for a way to deconstruct the colors of reality and reassemble them again by scientific means.

The Lumière Autochrome, invented and marketed by brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière, was the world’s first practical color photography process. The trichrome (publicised a few years earlier) was the first commercially available color process. It was complicated to use, as three separate pictures had to be taken of the same object through different color filters. Thus the autochrome became the first practical color process. After ten years of intensive research and development, the Lumière company introduced the first autochrome plates in 1907. The color pictures that resulted were on glass plates, and viewed as transparencies. They consisted of a color screen superimposed upon a black-and-white positive, which modulated the light passing through the color screen. While more modern color techniques – even those which also resulted in transparencies as the final product – exclusively used subtractive color processes, the Autochrome stands apart for employing additive color.

We can narrow the use of Autochrome photography down to a relatively precise period of fifty years: from the commercialization of the process by the Lumière Brothers (1907) until the final end of the technology’s production (1956/57). Its importance, however, had already experienced a significant decline by the end of the 1920s. A turning point came in 1931, when Lumière replaced glass plates with celluloid sheet film (Filmcolor) as its commercially available capture medium. After 1936, Autochrome had to contend with competition in the form of subtractive color process, from Kodak (Kodachrome) and Agfa (Agfacolor), which began gradually replacing Autochrome plates on the market.

A glass plate would first be coated with tiny, transparent grains of potato starch that had been dyed in the additive primary colors – red, green, and blue. These dyed grains were mixed and spread in even proportions over the plate, which as a result appeared gray when white light was shined through. The spaces between the grains were filled by a carbon black dye. A final coat, of a black-and-white photographic emulsion, came on top of that. When the photographer placed the plate in the camera, this final coat of emulsion was furthest away from the lens; when the lens was opened, light had to pass through the glass plate and through the colored grains before reaching the emulsion, although it was this emulsion that we actually talk about as being ‘exposed.’

Instead of being processed as a normal black-and-white negative, the plate would be subjected to a procedure known as reversal processing: the negative is developed, the developed silver is bleached out before an image is permanently fixed, and finally any remaining silver salts are developed in turn, producing a positive image. Once the plate had been processed and dried, it could be viewed as a transparency, appearing as a photograph in full color.

The Autochrome worked because the positive image – even though monochromatic – acted to modulate the amount of light that went through each grain of dyed starch. In a red area of the picture, for example, a lot of light would have passed through the red grains onto the coating of black-and-white emulsion when the picture was taken. The positive was lightly shaded in that area, so a lot of light would also pass through the red grains when the final transparency was viewed. The green grains in that same area would have blocked the red light when the exposure was made; less light, therefore, would have reached the plate at that place, making that part of the positive darker as well, so that the green grains, when viewed later, were “turned off” by the heavy deposit of silver behind them. In controlling the intensity of the three additive primaries, the Autochrome worked exactly the same way as the modern television or computer screen.

The brightness range of the Autochrome was limited for two reasons: the black matrix in which the grains were dispersed reduced the overall transmission of light, and saturated colors could only be achieved by diminishing the brightness of other colors. To make a strong blue, the red and green grains would have to be darkened, so saturated areas appeared as less bright, giving the Autochrome a tonal scale unlike that of any other process.

Part of what makes these early color photographs so fascinating for today’s audience is the unique perspective they offer, a glimpse into a period of humanity’s history we’re accustomed to seeing only in black and white – and that, in turn, we’ve grown used to imagining only in black and white as well. Just as the men and women of the early 20th century would have been amazed to see the world around them in such vivid mechanical reproduction for the first time, we in the 21st century find cause for astonishment too, not now in the colors of the present but the colors of the past.

Sources:

Richard Benson, “The Printed Picture”, published by The Museum of Modern Art, New York 2009.

John Wood, “The Art of the Autochrome. The Birth of Color Photography”, Iowa 1993.

Bertrand Lavédrine, Jean-Paul Gandolfo, “The Lumière Autochrome. History, Technology, and Preservation”, Los Angeles 2013.

André Barret, “Autochromes. 1906/1928”, Paris 1978.

Hanno Platzgummer, “Farben aus der Dunkelkammer. Die Autochrome des Franz Bertolini. 1908-1925”. Innsbruck 1996.

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

Pleasantville (movie trailer) 10 movies by The Lumière Brothers Kodachrome (movie trailer) Documentary: National Geographic - The Last Roll of Kodachrome

+49 89 29 73 42

+49 89 29 73 42