Category: BULLETIN

BULLETIN

The sea, for those who live along the coast, is an important and even indispensable source of food

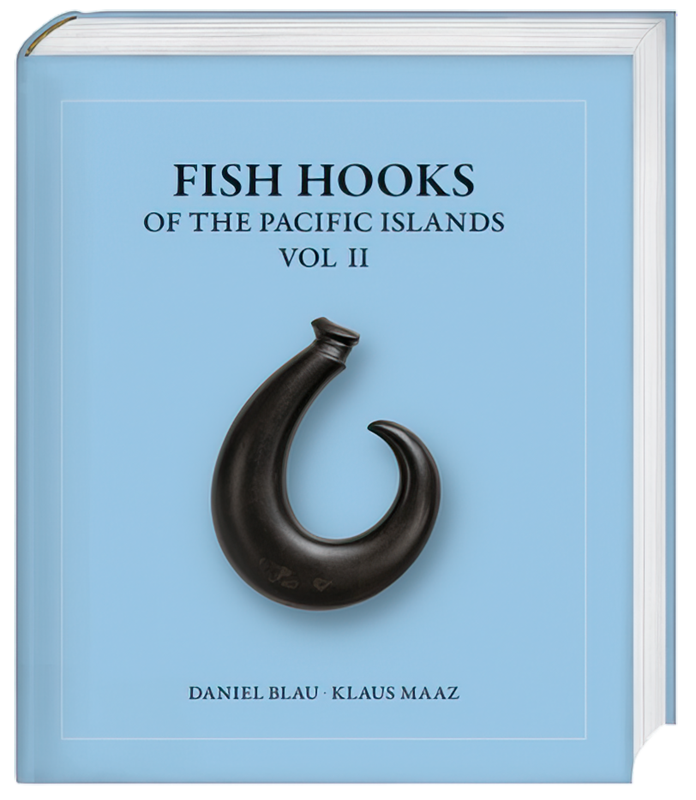

Fish Hooks of the Pacific Islands Vol II

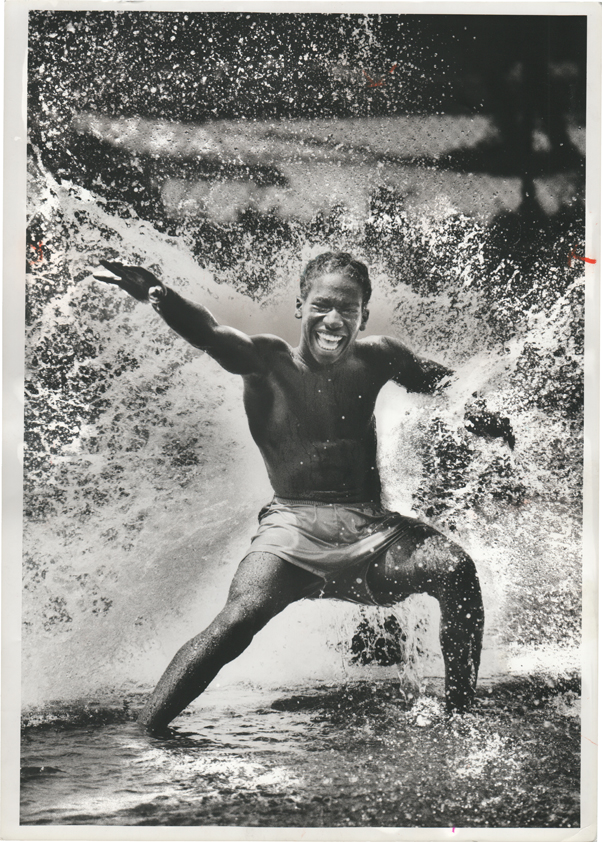

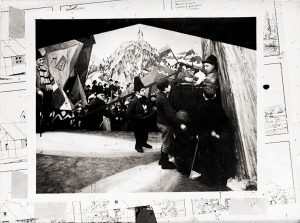

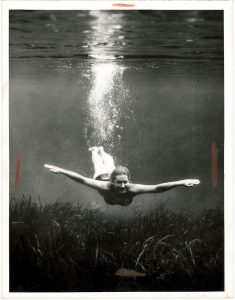

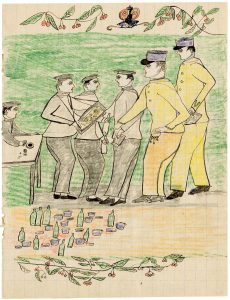

Bonito fishermen [Bernatzik, 1934: fig. 30](1)

For example: The Solomon Islands:

The sea, for those who live along the coast, is an important and even indispensable source of food. In the Pacific Ocean, this is especially true. Fishing became, more than purely a necessity of life, a ubiquitous social activity across all the archipelagos and lone islands of the vast Pacific realm, with distinctive symbols, rituals, tools, and sites defining cultures from the West Coast of America to Southeast Asia.

Solomon Islands, composite bonito hooks, shell, natural fibres, turtle shell, nylon, plastic, glass beads

The fish hook, a simple prehistoric tool embedded in our shared human consciousness and essential for the survival of many island civilizations, spans and unites these various cultures, beliefs, and practices, allowing us a glimpse into the soul of the Pacific. In 2012, Daniel Blau and Klaus Maaz published their first book on the subject, “Fish Hooks of the Pacific Islands,” through Hirmer. Their work served as an introduction and meticulous evaluation of fish hooks from across the entire region. Their comprehensive and passionate approach exemplified to readers the degree to which these items are more than just tools, more than just functional, but are in fact art in themselves, where the magic of each hook’s form combines with the rituals of forefather craftsmen and fishermen past. The hooks represent the visible, material part of a tradition stretching back to the dawn of human culture, serving as a sort of chronocultural marker whose forms continue to evolve in space and time.

In this case, the description of each object is essential. The maritime lives of Oceania’s inhabitants compelled them to create artefacts unique to each shore, even for the smallest and most remote islands. The trade networks made possible by the ocean enabled in turn a rich cultural exchange, and the spread of knowledge and material goods. Despite that exchange, though, the unique nature of each island or island group’s own production – the material and design of each island’s hook, the subtleties of its form or interaction of its component parts – survived.

Solomon Islands, composite bonito hook, shell, turtle shell, natural fibres, glass beads

More difficult to gauge at first glance is the precise, human nature of their use. The uninitiated have no clear path to imagining the interaction between hook and the hand of its crafter, the particular form of a given hook and the perfect technique for casting it. How exactly was each hook used? Which hook was best suited for which fish? The continuation of Blau and Maaz’s illuminating work, “Fish Hooks of the Pacific Islands Vol II,”, helps make the unimaginable real. This second volume draws us back once again to the fascinating world of the Pacific, deepening our knowledge of its diverse and complex fishing cultures, practices, and rituals.

Solomon Islands (Uki/Ulawa)

Solomon Islands, composite bonito hook, shell, turtle shell, natural fibres, glass beads

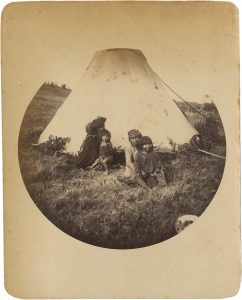

For the people of the Pacific, fishing became more than just necessary – it became sacred. Perhaps the best example is to be found in the so-called bonito cult of the Solomon Islands. “Fish Hooks of the Pacific Islands: Vol. II” paints a vivid picture for us:

Whereas the indigenous island cultures of Polynesia and Micronesia succumbed to the intrusive influence of Western civilization in the second half of the nineteenth century, the traditional culture of the Solomon Islands survived well into the twentieth century, including the all-important and omnipresent bonito cult.

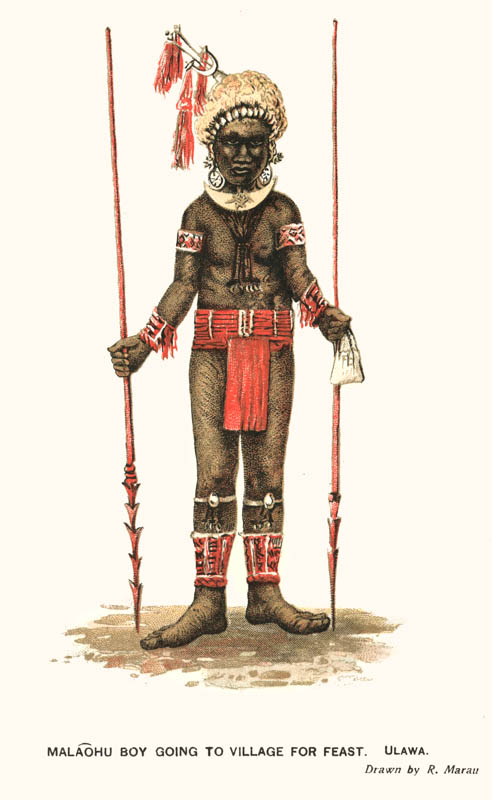

Particularly prominent in the islands of the southeast Solomons, ‘bonito cult’ is the term commonly used to refer to the entire, overarching environment of sacrality surrounding the bonito and everything related to it. This encompasses a vast range of practices, objects, and beliefs – sea spirits, fishing boats, traditions and rituals – but perhaps the most important and certainly the most visible single manifestation of the cult was to be found in the initiation ceremony of the Solomons, the sometimes months-long ritual process through which boys entered manhood – maraufu.

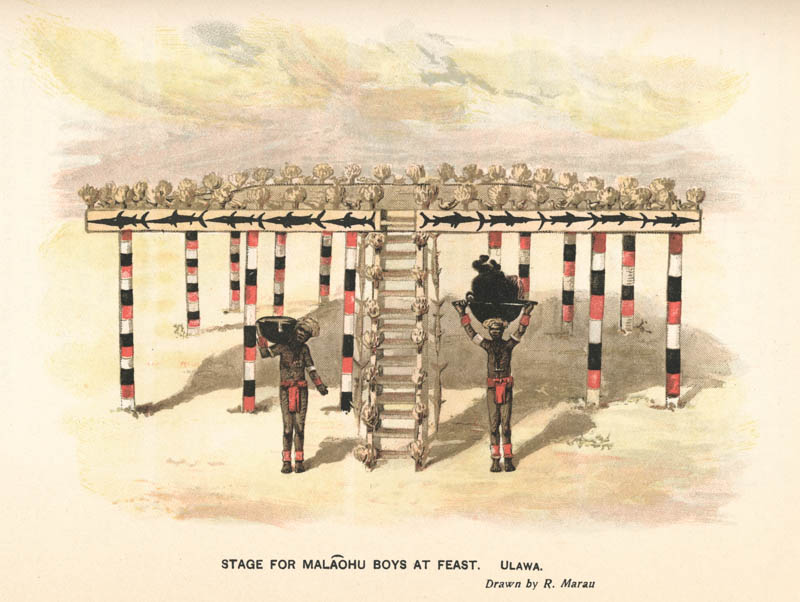

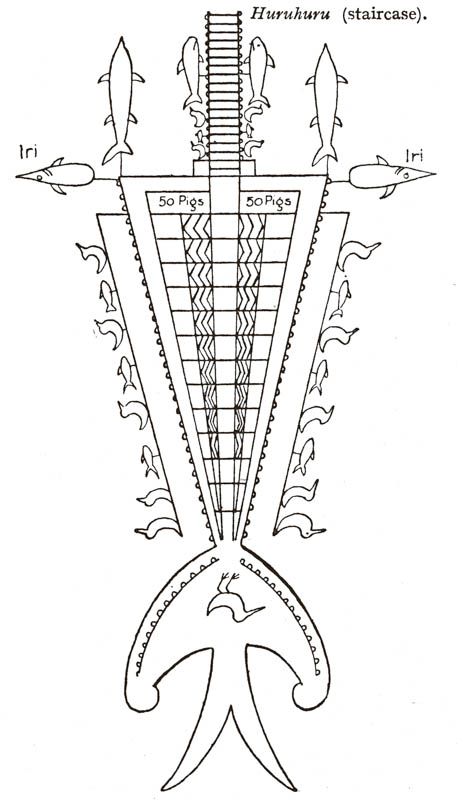

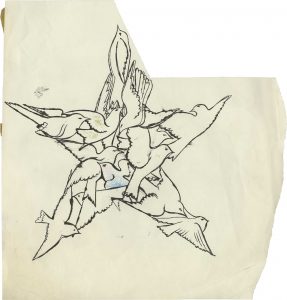

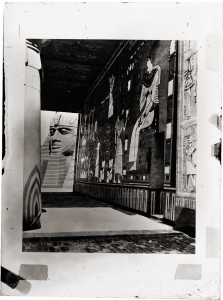

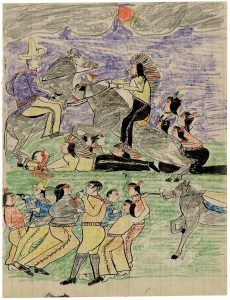

“Stage for Malaohu Boys at Feast”, Ulawa, drawn by R. Marau [Ivens, 1927:p.130-148] (2)

December through March is the windy season in the Solomons, the most important time of year for bonito fishermen. The season brings unfathomable schools of smaller fish past the islands’ coasts, and, following close behind them, large schools of sharks and other predatory fish at hunt, including, of course, the bonito. It is also in this season, therefore, that the initiation ceremony took place. Every boy had to undergo the initiation ritual, at about 13 or 14 years of age, in order to become a man, a process which, for the islanders, was intimately and inexorably bound up with the secrets of bonito fishing. Accordingly, the initiation process in its every stage and aspect is rife with bonito imagery and symbolism. The magnificent initiation platforms of the final ceremony embody this nearly mystical relationship in their very architecture. The basic form of the platform itself symbolizes a bonito, with its staircases acting as analogue to the great fish’s mouth. Entering the stairs, the boys, richly adorned and successfully emerged from their trials, symbolically enter the body of the fish. It is a moment that echoes an earlier stage and intermediate ceremony in the course of the long initiation process: after each boy returns from his first expedition alongside the experienced fishers, after he has caught his first bonito sat between the legs of his elder and grasping the rod with which the fish is hooked, he returns to shore, now an official maraufu or initiate-in-progress, where a priest awaits to cut the first-caught bonito open and anoint the new maraufu with its red, human-like blood, letting it drip across arms and legs, elbows and knees, cheeks, tongue – and flow even into the boy’s very mouth. The blood of the divinely-appointed bonito will, imbibed by those who will soon no longer be boys, make the body strong, keep joints and muscles young and sprightly. So now, at the culmination of their ordeals, do the youngest men of the island pass into the mouth of the fish.

right: [Fox, 1924: p. 348] (4)

Ngora-Ngora village on Ulawa Island [Bernatzik, 1934: pl. 13, fig. 13] (5)

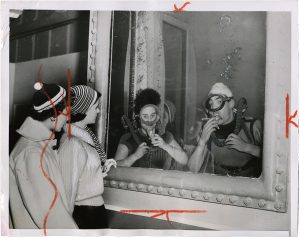

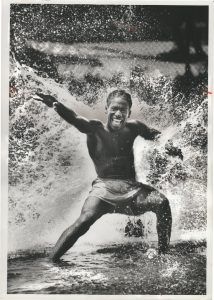

This final ceremony, the end of the entire initiation process, is treated with great fanfare and celebration by the entire community. Hugo Bernatzik was one of the last observers of southeastern Solomon communities when they still could be conclusively called traditional. His photographs of ceremonial platforms show wooden carvings of frigate birds perched atop the platform’s poles, above support beams jutting out and ending in their own elaborate carvings of sharks and predatory fish. Bernatzik’s camera also accompanied him when he went with bonito fishermen out to sea. He succeeded in capturing the dynamic majesty of the catch so fully that even audiences from our own century must admit to being moved by the images that resulted.

Solomon Islands, composite bonito hook, pearl shell, turtle shell with nylon lashings

This elaborate, ceremonial culture of the bonito bore witness to an ancient tradition of fishing, one which finally began to collapse before the onslaught of Western civilization in the second half of the 20th century.“Fish Hooks of the Pacific Island: Vol. II” brings the extensive, profound research and discourse of Volume I to a triumphant conclusion, casting a much-needed light upon the extraordinary, diverse, and fragile human genius of the Pacific.

“Solomon Islands, one-piece fish hooks, shell, pigments and plant fibre

This limited-edition book is the ultimate resource on the fish hooks of the Pacific Islands. More than 450 fish hooks and dozens of related objects are presented here in their true size (1:1) for the very first time, spread across more than 450 pages and more than 80 full-page or fold-out plates, and accompanied by 500 accessory illustrations, 45 photos of people and islands, 50 maps, and comprehensive expert commentary.

Foreword and texts by Daniel Blau and Klaus Maaz.

Essays by Anthony JP Meyer and Sydney Picasso.

30 x 25 cm, hard cover with embossing and dust cover.

Please contact us for more information: fishhooks(at)danielblau.com

appl Druck GmbH in Wemding, Bavaria

Bibliography

(1) Bernatzik, Hugo Adolf. Südsee (Leipzig, 1934)

(2) Ivens, Walter George. Melanesians of the South-East Soloman Islands (London, 1927)

(3) Ivens, Walter George. Melanesians of the South-East Soloman Islands (London, 1927)

(4) Fox, Charles Elliot. The Threshold of the Pacific (London, 1924)

(5) Bernatzik, Hugo Adolf. Südsee (Leipzig, 1934)

ORDER HERE ON DANIELBLAU.COM

Other Diversions

MAGAZIN BLAU INTERNATIONAL British Museum - Online Collections Expedition Magazine, Penn Museum: Male Initiation in Aoriki (Salomon Islands) Friends of Tobi Island Frontiers in Marine Science: Na Vuku Makawa ni Qoli: Indigenous Fishing Knowledge (IFK) in Fiji and the Pacific Frontiers in Marine Science: The Role of Ancestral Seascape Discontinuity and Geographical Distance in Structuring Rockfish Populations in the Pacific Northwest Future Exhibitions and Installations at the Getty Centre, California Tavake Pakomio: Learning from our Ancestors: Exploring Ancestral Island Wisdom and Practices on Rapa Nui The Pacific Collection Access Project - French Polynesia, Google Arts & Culture The Serious, Sustainable (and Sometimes Celebratory) Indigineous Fishing Methods of Polynesia Women and Fishing in Traditional Pacific Island Culture Cook Islands: Traditional Fishing Methods 2012 Pacific Island Ethnic Art Museum, California

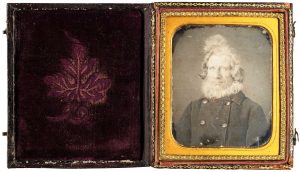

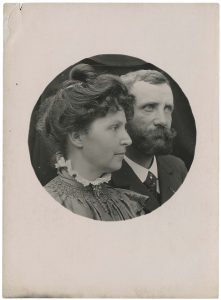

The Daguerreotype initially took over from silhouette paper cutting (Scherenschnitt) and portrait painting and drawing

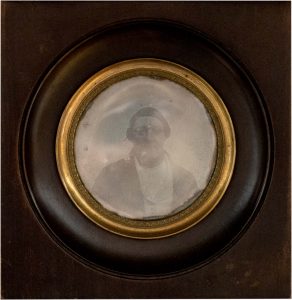

Precious Pictures The Daguerreotype-Memento

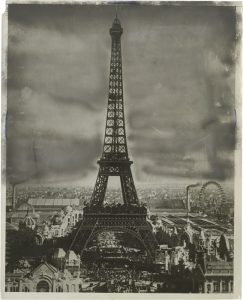

When we speak of Daguerreotypes, we are referring to the earliest photographs, those made possible through the process advanced by and named after the Parisian Louis-Jacques-Mandé-Daguerre (1787-1851). The process saw a silver-coated copper plate exposed to iodine fumes, thereby creating a light-sensitive layer of silver iodide. The next step was to expose the copper plate to light from within a camera obscura. The plate – for the time being still looking exactly the same as it did before exposure – would be removed from the darkened box of the camera obscura and exposed to mercury fumes. At this point the picture was developed and visible to see; bathing the plate in a saline solution, then washing and drying it, would fix that picture permanently to the plate. Each daguerreotype was a completely unique item, not capable of further reproduction. The heritage of the invention extends beyond Daguerre himself – he made use of various physical, optical, and chemical laws and properties that were already known and understood. The camera obscura, for instance, had been in use as an aid for creating perspective drawings since the fifteenth century. The photosensitive properties of silver salts had been discovered by the German medical doctor Heinrich Schulze at the beginning of the eighteenth century. Even the photographic process itself was already known to science, thanks to Joseph Nicéphore Niépce. Niépce developed a method that required an exposure time lasting hours; thanks to Daguerre’s invention, that could be reduced to mere minutes.

Bodo von Dewitz and Fritz Kempe, Daguerreotypien. Ambrotypien und Bilder anderer Verfahren aus der Frühzeit der Photographie. Document of Photography 2, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg, 1983. p. 31

In a lecture at the Academy of Sciences and Fine Arts in Paris on August 19, 1839, the physicist François Dominique Arago at last announced the final details of the technical process that he had been involved in developing. With Daguerre, who gave his name to the first widely available and practical photographic process, a centuries-old scientific dream had come true. Daguerre had presumably begun the relevant experiments in 1825. Niépce and Daguerre had agreed to share the financial windfall of their research, should it prove successful. Arago, Daguerre and Niépce’s son – his father having, in the meantime, passed away – offered the invention to the French government in exchange for the payment of a lifelong pension. The French state bought the patent and released it to the public as a generous gift “à tout le monde.” Daguerre took his pension – 6,000 francs per annum – and retired to a private life in the countryside, where he died in 1851.

Volker Jakob, „Menschen im Silberspiegel: Die Anfänge der Fotografie in Westfalen.“

In Aus westfälischen Bildsammlungen, Vol. 1, ed. Wolfgang Linke, Eggenkamp Verlag, Greven, 1989. p. 11-12

When the process was made public, news reports began flying off the presses around the world, and a genuine ‘daguerreotype fever’ broke out in Paris. Contemporary reports speak of countless enthusiasts crowding the squares and streets with the first Daguerreotype cameras in hand. The demand for the devices seems to have been so great that production wasn’t able to keep pace. Some amateur photographers even attempted to create homemade versions. The Daguerreotype initially took over from silhouette paper cutting (Scherenschnitt) and portrait painting and drawing. Anyone could have life- like portraits of family and friends. This kind of memento gave rise to the fame and the propagation of the Daguerreotype. The metropolis of Berlin was the new art form’s first center in Germany, playing its part in ensuring the Daguerreotype method’s continuing spread and dissemination. Readers wanted new information and news reports constantly, and the press gave its all to keep its readers satisfied. Daguerreotype chemicals and the associated tools were readily available, supporting the experimentation of early photographers.

Jochen Voigt, Der gefrorene Augenblick. Daguerreotypien in Sachsen 1839-1860. Chemnitz, 2004. p. 13

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

How was it made? The Daguerreotype by Victoria & Albert Museum Daguerreobase Dark Valley Das finstere Tal Daguerreotype | Le Secret de la Chambre Noire

Writings on the Daguerreotype | Photoinstitut Bonartes (Albertina)

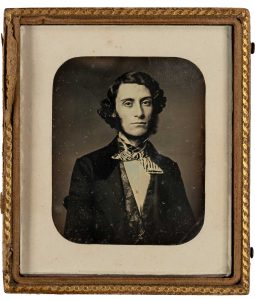

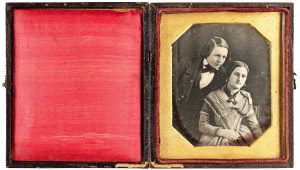

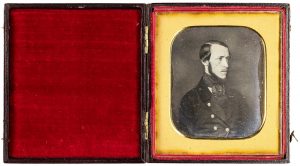

“Anonymous Portrait”, 1850s,

daguerreotype,

6,1 (9,5) x 5,0 (8,2) cm, ©Daniel Blau, Munich

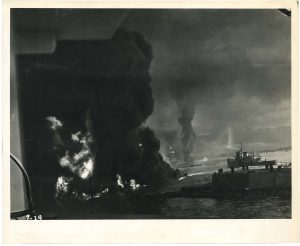

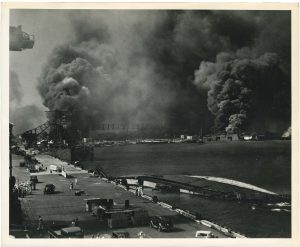

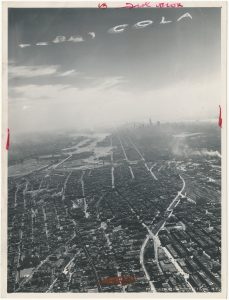

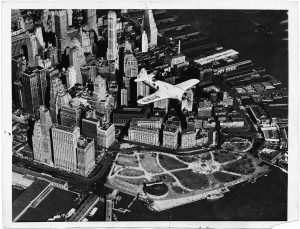

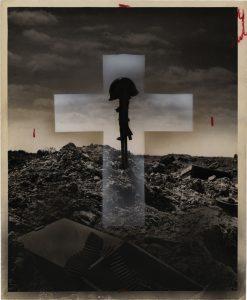

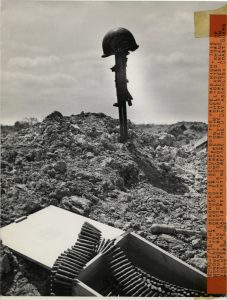

Daniel Blau has assembled an outstanding collection of photographs bearing testimony to the attack

Kronos: Fire and Water

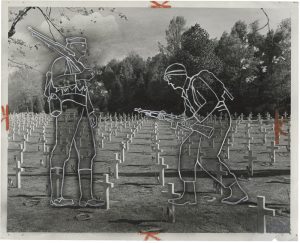

Strife and war are driving forces for mankind. Depictions of the hunt and scenes of war, of sword and spear, appear in our record even before recordkeeping, in the prehistoric cave paintings of Lascaux, the rock art of North Africa and Europe. We have, even from the earliest times, used our art to show our weapons at work exerting dominance over the natural world and our fellow man alike.

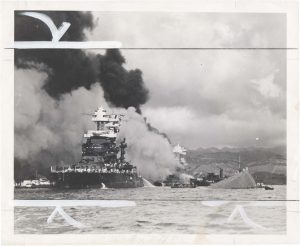

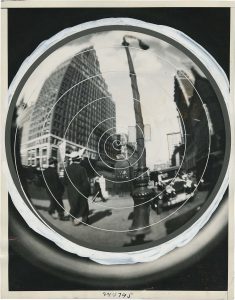

Sunday morning, December 7th, 1941: a grainy image shows Hawai’i from a bird’s-eye view. The island, the harbor, and a row of ships. Concentric waves. A torpedo has dropped into the water to leave those waves behind; in just a few moments it will hit one of those ships, and explode. The photo has captured the precise moment when the USA comes under direct attack by Japan. The attack on Pearl Harbor, more than any other single event, is what transformed a European war into a truly global one, a world war in all its senses and with its consequences.

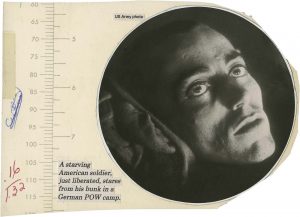

Daniel Blau has assembled an outstanding collection of photographs bearing testimony to the attack. U.S. Navy photographers are found here alongside the much rarer work of their counterparts within the Imperial Japanese Army. This contrast and compliment permits a vivid, haunting insight into this brief instant in history, this era-defining attack, and forms the basis for a deeper engagement with war photography at large and the artistic considerations and aspects involved.

Nearly 81 years ago, Japan’s surprise attack on the US Pacific Fleet in Pearl Harbor brought about World War II’s turning point: the entry of the world’s most powerful military might, the USA, into the war. The unanticipated act of war lasted only about two hours. It came in two waves, claiming the lives of over 2,000 American soldiers and civilians. The photographs from our present collection illustrate almost every single military step taken by the two sides. The first Japanese bombers flew over Pearl Harbor that day at 7:48 am Hawaiian time. Their targets included, among others, seven US Navy battleships anchored in the vicinity of the Ford Islands, along the so-called ‘Battleship Row.’ In the course of those two attack waves, each lasting only a few minutes, 353 Japanese fighter jets and 28 submarines destroyed three US battleships and inflicted considerable damage on the remainder. The Americans were able, all the same, to shoot down 29 enemy planes.

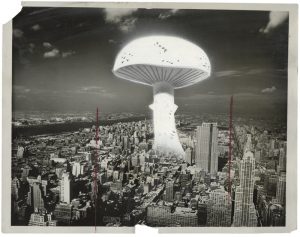

The progression of weapons at human disposal has been matched by the progression of our illustration of them, from the dawn of art down to today. Rocks for bludgeoning and hurling gave way to the sword and the spear; the spear turns to arrow, to bullet and bomb and torpedo, until ultimately, in our own age, the long destructive evolution culminates in Fat Boy and Little Man, the atomic bomb in use, something like a response to the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The moment those first torpedoes dropped from Japanese planes above Hawai’i is also, then, the same decisive moment upon which the lives of hundreds of thousands in Hiroshima and Nagasaki hung. It is also, though, the moment in which the USA decided to demand an end to German hubris and arrogance. In a sort of paradox, then, the most important event of the 20th century was not so much a world peace, but rather the world war which engendered it.

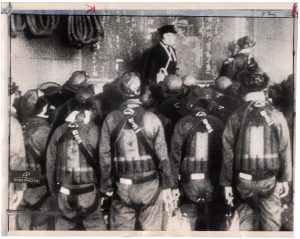

A deeply symbolic photograph, the earliest image from the attack, was shot from a Japanese warplane. The arial photograph clearly shows the torpedoes that hit the US Navy warships stationed along the coast. Our exhibition, however, begins with a photo taken from a Japanese newsreel, published much later in the war. Japanese fighter pilots can be seen being prepared for their mission on board an aircraft carrier. Pilots of the Shimpū Tokkōtai, the Japanese kamikaze unit, are given a symbolic sip of sake; they do not expect to survive their mission.

The most widely published of these photographs originates with photographers of the US Navy. It shows the USS Shaw, a small and fast warship of the class known as ‘destroyer,’ at the instant of its explosion in dry dock. The tragic moment, the exploding ship itself, all is framed by palm fronds and an otherwise idyllic scene. Holiday paradise and bloody conflict come directly face-to-face. Clouds, the fireworks of explosion, the bursting apart of the USS Shaw, all appears together like the elements of some old master’s oil painting.

It is here that the matter of artistic photography comes to the fore. The pictures made by both the Imperial Japanese Army Photographers and the US Navy photographers serve as valuable source material, chronologically documenting not only the attack on Pearl Harbor itself but also our very knowledge of it; through the visual language in use, through the spectacular motifs, through the thick swaths of smoke and formations of ocean cloud, in every shade and nuance of greyscale, these photographs also bring their enormous artistic and emotional worth before us, more than purely documentary evidence of the sinking wrecks, the uniformed young and old men alike on the docks and on doomed ships. These are artworks, showing their artists’ every effort in grasping towards a profound aesthetic in that hectic and instantly fleeting state of being which is war.

The timeline reasserts itself in another photo, taken May 24th, 1943: the slow and arduous salvage of the USS Oklahoma is underway. Throughout the 17 months following Japan’s surprise attack 16 of the 19 sunken ships were recovered by the Navy and put back into service. In the wake of such terrible events, a photograph like this can serve to grant man once again hope, a sense of security and faith in our capacity not only to survive but to rise up ever stronger.

Every single photo gathered here serves as an important document of its time. Most of these photographs also find elaboration through the original text or newspaper reports (slugs) included on the back; the word choice and the language of these texts opens the images up to us on yet another level, allowing each recipient to ‘read’ the image of the war again, as though through new eyes or with deeper understanding. Amongst all this abundance of art-historical objects and photographs, it remains the image itself, the reproductive depiction of an event – and this was as true then as it is today – which is taken as the ultimate proof of occurrence. We use words to name objects and occurrences, to give some meaning and purpose to them. But we also, in just the same way, rely upon the portrayal of history-laden events, whether in the form of something sketched or photographed, to bring us towards belief in the truthfulness of what has happened. Here we might look to the buried photographs of the Buchenwald concentration camp as an example. Images have enormous influence on the very way in which we see; they reflect political and military structures, can even be used, ultimately, as evidence in court proceedings, in investigation for instance of war crimes. The space always left for interpretation within a photograph’s frame, however, can also serve as space for propaganda. Photography always anchors itself, in our collective visual memory, as a genuine reproductive depiction of one moment. These different dimensions lead also to an understanding, though, that the recipient too must be held responsible: he must cast his thoughts to matters of seeing, of not-seeing and of not-wanting-to-see, and must pose to himself the question of what it is that in the last accounting remains as the real expressive significance of the photo. It is up to him to close the invisible hole in history that has opened up between the reproduced depiction and the real event itself.

“Kronos” is available for purchase as a set. Price upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

This offer is noncommital. We cannot guarantee the set is still available on request.

Other Diversions

Examine the facts and timeline of the Attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 The National WWII Museum - Pearl Harbor Attack, December 7, 1941 Naval History and Heritage Command View footage of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor U.S. Navy Pearl Harbor - The Attack and Aftermath Film “Pearl Harbor”, 2001 Pearl Harbor History

“Pearl Harbor Attack, Photographed from Japanese Bomber”, December 7, 1941,

vintage silver gelatin print on glossy paper, printed in 1942 in Germany,

17,1 (18,0) x 23,5 (24,4) cm © Unidentified Japanese Photographer, courtesy Daniel Blau Munich

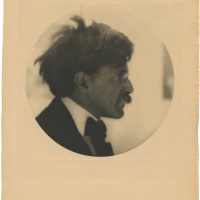

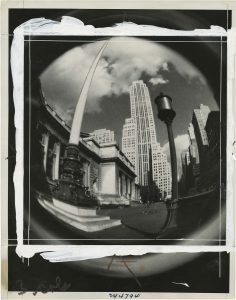

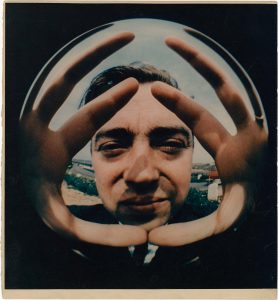

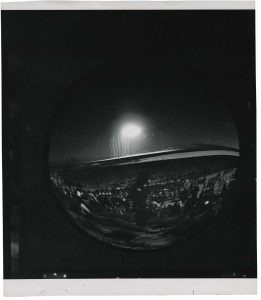

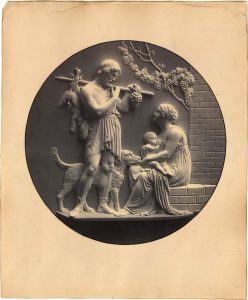

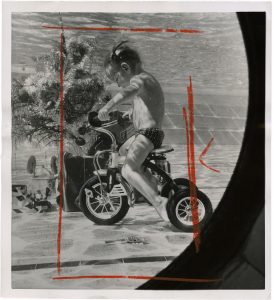

What is the aesthetic beauty of a circle, or of a turning, curving movement?

Tondo

Daniel Blau: Maybe we should start at the beginning. Do you remember when we first came up with the idea of putting round photos at the center of a show?

Serge Plantureux: The exact conversation? We were together, we were discussing several matters… you also had an interest in various subjects we discussed, like broken negatives. I think it was in the same conversation. We were looking for how to make a beautiful exhibition on a subject linked to a material aspect of photos.

DB: Yes, that was over 10 years ago!

SP: Oh yes, yes, more than 10 years!

DB: Yes… it was actually a fun time in Paris, lots of auctions.

SP: But I think it was even before Lehman Brothers.

DB: Yes, before Lehman Brothers. What is it that’s interesting about round photographs? Why did we decide on round pictures rather than damaged negatives? Which I still think is also a very good subject.

SP: Because of resources. It had to do with how many we hoped to find. How difficult it is, how rare the subject is. Damaged negatives… we started that as well, I think. But it didn’t develop into anything…

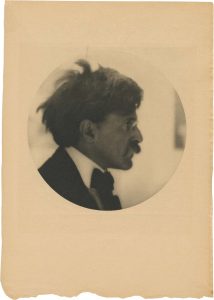

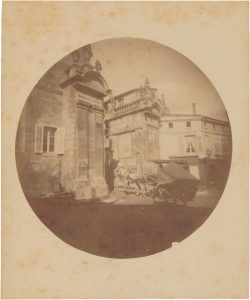

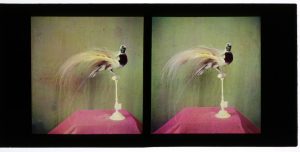

Roundness has a symbolic aspect to it. There are circular images made on purpose. There is something linked to the optical, something linked to the history of photography – for example, the Voigtländer camera in 1840. There is also the circular cutting-out of paper from a square original. So there are a lot of angles, and it is a very dynamic and creative subject.

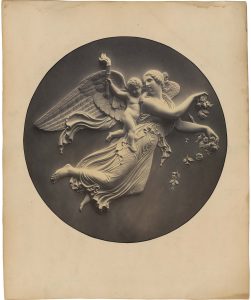

DB: I agree. Roundness in art – as with the tondo – has been around a long time. Maybe the most famous tondi are in the Uffizi, the Medusa’s Head by Caravaggio or the Madonna del Magnificat by Botticelli. You have a lot of round pictures in art history.

But round is also complicated. It is complicated in regard to framing, it is complicated in regard to process. You naturally have a lot of waste when you produce a round canvas or a round photograph, because you cannot divide a piece of paper into circles without loss. Therefore, the tondo is not very common in art, in photography. Even now it is not very common. But we found quite a few round photographs. Why do you think that’s the case?

SP: We found a few because we were kind of active, and efficient. We had access to many different collections and we had no time frame.

DB: Yes, no deadline…

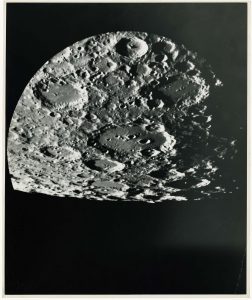

SP: We could cover all periods. It would be more difficult to put a substantial show together if you wanted to find roundness in modernist photography only, or in calotype. But once we accepted every period, we found the tondo in every generation, and found that, in fact, tondi from one generation to another are very different. In earlier times, some roundness was linked with microscopic investigation, because the image done with the microscope is already round by essence.

DB: Yes!

SP: Also, you had a lot of interest yourself, and I only discovered this on that occasion, in sténopé images. Most of the sténopé are round because of the pinhole. So, pinhole camera images are round with black margins… so they can be printed on square paper, but the image is centered in the middle of the print.

DB: What is the aesthetic beauty of a circle, or of a turning, curving movement? Isn’t it something that is quite natural to us? Beginning with the iris being round, and the eye being round like a sphere, and the head being roundish, the sun and the moon being round. We are surrounded by all these spherical and seemingly circular objects.

And don’t you think it’s surprising that, from the beginning of photography, the photo camera’s lens, which is naturally round, never square – and even a rectangular lens would create circular images – produces an image which is also round, a tondo, circular, yet results in rectangular prints? Wouldn’t you think that the carrier of the image, subsequently, should also be round? Sure, there are examples of circularity. Among the very earliest photography in France, you find daguerreotypes that are round. You mentioned the Voigtländer camera. But the history of the photography turned firmly to the square and the rectangular. Why, in photo history, is there not a continuation of circular photographs, based on the shape of the lens?

SP: Because it’s more expensive to produce Daguerrean round plates. Logistically it’s more difficult. It’s more difficult to store them. Except for eggs, most food is cubically stored, stacked.

DB: And they’ve even tried to make eggs cubical! So it’s an economic reason.

SP: I think so!

DB: That is probably correct! But photography is an art form. And wouldn’t an artist try to break out of economic boundaries to produce something that is artistically beautiful, or ugly, whatever his intention may be – but unrestricted by the common norm?

SP: It is a very interesting discussion, and it could make a beautiful exhibition. A real artist trying to break economic boundaries.

DB: Yes! The question is, again, why do photographers, as artists, stick to the boundaries of square or rectangular paper?

SP: Because every paper is produced square or rectangular.

DB: Didn’t artists in the early days make their own paper?

SP: Yes, but you still needed to buy the sheet of paper – they made an emulsion, not the paper itself.

DB: Yes, of course!

SP: Only in Daguerre’s time was there really an opportunity of choice, between the Voigtländer camera and the square Daguerre camera. But in other periods, every negative produced was either square or rectangular.

DB: There is the Kodak I and II, and they produce round images…

SP: … on square paper…

DB: Strangely enough, on square paper… exactly. But at least aesthetically they stay with the tondo, with the circular. I mean, round is just more pleasant to look at than rectangular. The anthroposoph knows that better than anybody else.

SP: Because of anthroposophy I’m thinking… Did we find round autochromes or not? I don’t think so…

DB: I don’t recall round autochromes. I mean, there are autochromes that are circular or oval in square or rectangular glass sheets. But I haven’t seen a round autochrome.

And you have the additional problem with the autochrome that you would have to cut the glass into a circle, which is not so easy.

SP: Oh yes, I’m also thinking of color. We found some round positive photograph images from Japan. The Japanese were interested in the idea of round images for glass positives.

DB: I can see that, with beautiful wooden frames, yes, I can see that! So even with Braun or Bisson, who did carbon prints on glass, you know – these stained-glass photographs of glaciers and alpine scenes that they produced – even with them I never saw stained-glass in the round.

SP: No, I agree…

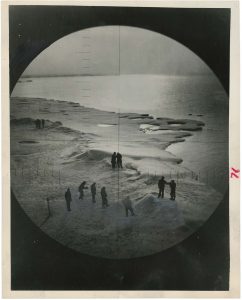

DB: Back to the round photographs that we managed to find. It was easier to find images in the round after the fish-eye lens became popular, at the beginning of the 1930s. The extreme wide angle gives a gravitating effect on the paper. If you cropped it square, you lose that. So, a lot of those first fish-eye lens images are actually circular on rectangular paper. For earlier periods it was not easy to find really good examples. Why do you think that is?

SP: Why? Because of the mimetic desire of photographers. You say some artists like to break the rules but most want to do the same thing… I don’t remember if we found what the first big success was, but I think there was a huge success with the fish-eye lens, and many people became interested in following up on that example. In the ‘60s and ‘70s it also connected with the spirit of the time.

DB: It’s a very simple and very impressive effect.

SP: Maybe the tondo was considered bourgeois by the avant-garde of the early twentieth century. That’s possible also!

DB: And there is also another effect. A lot of photography was made for use in newspapers. Do you remember that, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, photographs which newspapers and magazines inserted into their texts were sometimes, even frequently, cropped round?

SP: Yes!

DB: In newspapers and magazines you’ll have a picture that is cropped circular because that somehow fits the design and the layout of the text, but I don’t recall finding any prints in newspaper archives that were cropped circular. So even if the original was square, the person doing the final layout would decide when to use it as a round image, and when not to…

DB: Again – economic reasons?

SP: If you consider an apartment, and you have a perfect wall, you can mix drawings, photographs, and paintings, but it’s not so easy to insert a round image on that wall… a round image or round frame can easily break the harmony.

DB: It could. Especially if it’s a little darker it looks like a hole. I mean, when you poke through something, the resulting hole is usually roundish. In painting, some modern and contemporary artists did round paintings. Damien Hirst did huge splatter paintings that are tondos – there’s also Baselitz, or Mondrian or Lichtenstein. But I know from experience no part of that is easy to do, beginning with the cutting and stretching of the canvas and up to the framing of the painting itself. And none of the framing studios are really equipped for roundness. It is extremely uncommon, extremely uncommon in art to find tondos these days. Some do it, but not many.

SP: If you consider social media, where you have billions of people playing around for likes on Instagram, it’s not so easy to insert round images into a river of images which are all of another format.

DB: That reminds me of a concert I heard yesterday. It was a piece by [Alfred] Schnittke, a rather modern composer. There was a break, to be followed by a piece by [Anton] Bruckner. And during the break, the people in front of us were talking to another couple. She was complaining that in Schnittke she heard no harmony, nothing musical that would be pleasing to her ears. She said: “Why do we have music if it isn’t harmonious to us?” And I’m thinking, the music that we hear today, just like the pictures that we’re looking at today, they are the result of a common understanding and usage. So, in the same way that we’re used to rectangles for economic reasons. The German word for this is Sehgewohnheiten. The way that we look and perceive is accustomed to the rectangular, and not to the circular. But let’s imagine everything had started out differently, if we weren’t used to ‘our’ kind of music but to what is produced in the Amazonian jungle, or somewhere else. Our Hör- and Sehgewohnheiten – our listening and viewing habits – would be quite different. Therefore, if [our world] wasn’t all industrialized the way it is, leading to square and rectangular everywhere in photography, maybe everything would be rounded, and if we saw a square photograph it would be surprising and irritating to us. I think it has a lot to do with habit and lobbies.

SP: Maybe yes, but can we go back to the personal house, the personal family flat? The round image is somehow very powerful in the way that it looks like a center. It looks like a direction – if you have one image isolated on the wall, for example, all by itself. Or you can have small ones, which are like punctuation. Round images are like the punctuation of a grammatical aesthetic phrase. A cultural aesthetic decoration of the room.

DB: Think of the Guggenheim, when the Guggenheim was built. Roundness is the main concept of the building. It is not easy to use. It is not easy to play with for exhibitions. It is possible. But the perception that you have, as a visitor, of the art in such a building, one that isn’t rectangular or square, is fundamentally different from when you walk into a square building, like the Guggenheim’s own Thannhauser annex. And there are cultures, there are people who are not used to angled-room buildings. I’m thinking of – you remember – the [Paul-Émile] Miot photographs that were done in Africa, in Senegal in 1870. In the background you see these clay houses that are like domes, so are not square. And can you imagine hanging square photographs in such a space. A round photograph would make much more sense.

SP: Yes.

DB: More related to the viewer.

SP: Ok, so I think the title can be “Most Photos are Squares Because Our Houses are Rectangles.”

DB: Yes, that’s exactly what I think. It is a decision that was made for economic reasons, most likely, that is embedded now in our visual understanding. Can you imagine if our telephones, our smart phones, instead of being square were round… ! If Apple decided to come out with a round telephone. Millions of people would buy that round telephone because it’s round and not square. That would change our visual understanding again, and I think the tondo would become more pleasant to us, and more common.

SP: Yes, perhaps, but I doubt it. For example „zooming“, I couldn’t have my telephone standing on the bar table here, if it was a disc or circle. It would roll right off!

“Tondo” is available for purchase as a set. Price upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

This offer is noncommital. We cannot guarantee the set is still available on request.

Other Diversions

The Globe Shakespeare Leonardo Da Vinci - The Vitruvian Man Albrecht Dürer - The Virgin and Child Crowned by Two Angels above a Landscape The Rotating Discs of Marcel Duchamp Vasily Kandinsky: Around the Circle Video: Vasily Kandinsky “Around the Circle” Movie Trailer “Vertigo” by Alfred Hitchcock Jules Verne - Around the World in Eighty Day 19th Century Street Photography With a Spy Camera The Guardian - In the round: centuries of circular design – in pictures The Met Museum - Kodak and the Rise of Amateur Photography Tate - Damien Hirst “Round” Uffizi Museum - Holy Family, known as the “Doni Tondo”

“Alfred Stieglitz”, 1908,

photogravure, printed in 1908,

15,9 (30,0) x 15,9 (21,0) cm, © Daniel Blau, Munich

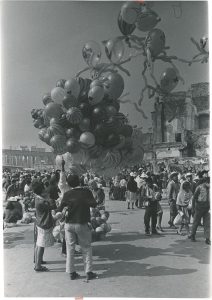

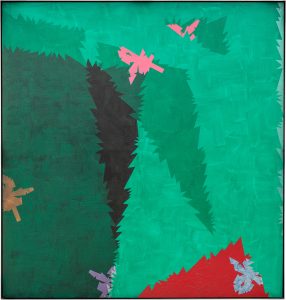

Birds have been revered in many cultures throughout history

Birds or “Der Traum vom Fliegen”

Humans across the ages have dreamed of flight, inspired by the movements of birds and the passage of clouds. The history of aviation goes back more than two thousand years – to early kite flying in China that can be traced to several hundred years BC. The tradition of flying a kite spread around the globe and is considered to be the earliest form of human flight. Kites represent a meeting place of man and elements, similar to the way in which sailboats harness the power of the wind to propel their motion.

In the 15th century, Leonardo da Vinci’s fascination with flight accompanied him from his youth throughout his entire life. He was devoted to finding ways to allow man to fly, making numerous studies and observations of birds, analysing their flight technique and the structure of their wings.

He created countless sketches, drawings and models in the attempt to create a flying machine that could be propelled by a human, but he came to understand that a solitary person wouldn’t be capable of producing enough energy to move the wings, so another form of mechanical flight would be necessary.

The first hot air balloon flights took place in the 18th century, a time of rapid developments and discoveries that contributed to our understanding of aerodynamics. Balloons were also deployed for military purposes from the end of the 18th century. From the earliest days of aviation, flight has been associated with both adventure and war. The dream of flight led to modern aeronautics, with the Wright brothers’ first successful aeroplane flight in 1903.

This swiftly led to record-breaking moments in history and technological innovations that played a huge role in the conflicts and connections that have shaped our contemporary world.

Birds have been revered in many cultures throughout history

Around the world, birds have been revered and considered symbols of life, death and fate. They have appeared in folklore and popular culture, from prehistoric cave paintings to national flags. They’ve been the focus of superstition, myth and worship in many indigenous cultures and were regarded as expressions of God in early African and Egyptian cultures.

As a theme they have inspired many artists, manifesting as motifs and signs.

Birds have represented freedom, pride, the afterlife. They have been portrayed as mystical and mundane. They’ve made countless appearances in stories and films.

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

Die Zauberflöte Film 'The Maltese Falcon' „Surfin Bird“ by The Trashmen Bird Watching in Georgien Walther von der Vogelweide „Aphorismen“ Nationalapark Wattenmeer

“Iwo Jima, Airfield Is Life-Saver for B-29´s”, March 31, 1945, ©W. Eugene Smith, courtesy Daniel Blau, Munich

Today they are disappearing, for they have no place in digital photography

Caligari, Golem & Co. – Glass Negatives

Negative:

The photographic record exposed in the camera, so called because it renders light values as dark and vice versa. Negatives have ranged widely in the materials of their support, from paper to glass to flexible film. Today they are disappearing, for they have no place in digital photography.

Richard Benson, The Printed Picture, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2008, p. 324

The first fully practical process for negatives on glass was introduced by F. Scott Archer in 1851. A sheet of glass was handcoated with a thin film of collodion (guncotton dissolved in ether) containing potassium iodide, and was sensitised on the spot with silver nitrate. The plate had to be exposed while still wet, and developed immediately.

Brian Coe, Mark Haworth-Booth, A Guide to Early Photographic Processes, Victoria & Albert Museum, 1983, p. 18

The use of a film of sensitised albumen on glass was first proposed by Abel Niépce de Saint-Victor; the albumen plate gave very high resolution of detail but was very slow, requiring long exposures. In the 1850s it was employed in combination with collodion or gelatin in the preparation of dry plates. Albumen negatives are not commonly met with, and in any case, are almost impossible to distinguish from collodion negatives, at least not without complex chemical tests.

Brian Coe, Mark Haworth-Booth, A Guide to Early Photographic Processes, Victoria & Albert Museum, 1983, p. 17

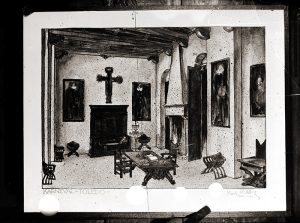

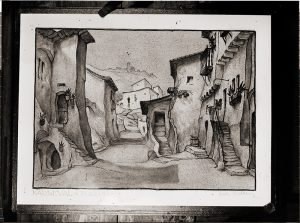

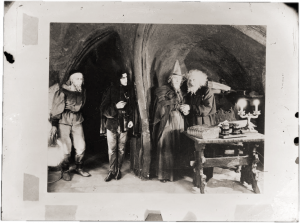

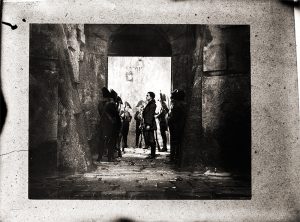

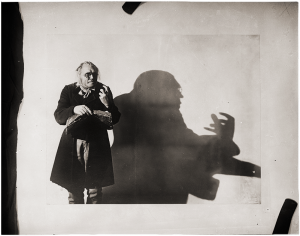

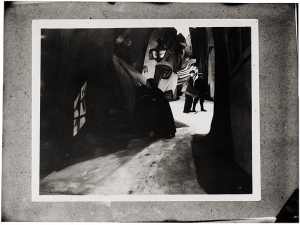

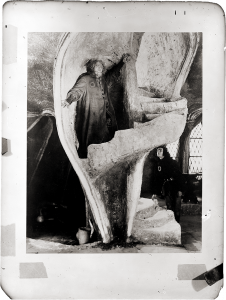

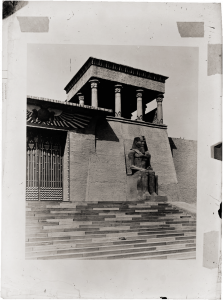

Sumurun

Baghdad, 9th century: Sumurun, the sheikh’s favorite wife, is fed up with life in the harem. When her love for a cloth dealer is exposed, the sheikh finds a replacement in the beautiful dancer of a traveling juggling troupe. But he is not her only admirer. His son and a hunchbacked juggler both have their eyes on the dancer as well, all competing for her attention. Intrigue and murder ensue.

Sumurun is based on one an ‘oriental fairy tale’ by Friedrich Freksa, who produced it as a pantomime filmed by Max Reinhardt in 1910. The director and star of Sumurun, Ernst Lubitsch, had begun his acting career with Reinhardt, and so Lubitsch’s 1920 remake of the pantomime original serves simultaneously as an homage to the artistry and imagination of his old teacher.

Lubitsch

Ernst Lubitsch was born in Berlin in 1892. After attending high school he began an apprenticeship in a fabric store and worked as an accountant for his father, a tailor. In 1910 he began acting lessons at Max Reinhardt’s Deutsches Theater. After a number of smaller roles, he made his true film debut in 1913, in The Ideal Wife. From 1917 he worked with a small staff as a director at the recently-founded Universum Film AG (Ufa). In 1923, after a run of successful period films like Madame Du Barry he moved to the United States, where he worked as a director for various Hollywood studios. A host of sophisticated social comedies resulted, including The Marriage Circle and So This Is Paris, with subjects drawn mainly from European literature. Keeping an eye on the strict censorship regime of the time, Lubitsch developed an ironic technique full of allusions and hidden meanings, indirect commentary and elegant whispers. All this became known, and has gone down in film history, as the “Lubitsch touch,” an approach to filmmaking which deeply influenced the development of American film comedy from that point on. His first sound film, The Love Parade, represented an even further leap forward in genre and technical capability than in its use of sound alone; it is one of the first true film musicals, not merely a filmed version of the earlier stage operetta it was based on but a true adaptation for the cinematic medium, using the possibilities of film (montage, moving camera, and so on) to unprecedented effect, and achieving a true union of image and sound on screen. Ernst Lubitsch died in 1947, in Hollywood.

Source: Deutsches Historisches Museum

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

Silent Film Archive The Silent Film Channel Film: Sumurun (1920) The Rediscovery of the 'Sumurun' Movie Soundtrack (composed by Victor Hollaender) Film: The Cabinet of Cr. Caligari (1920) Film: The Loves of Pharaoh Film: The Golem (Der Golem, wie er in die Welt kam) Murnau Foundation

© Unidentified Photographer, courtesy Daniel Blau, Munich

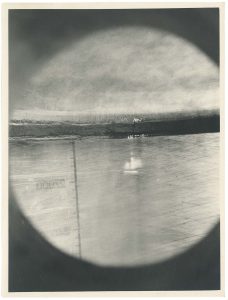

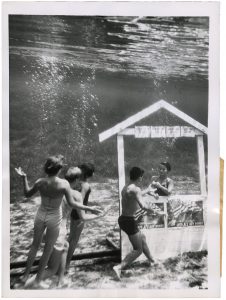

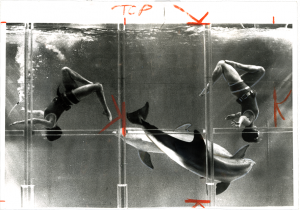

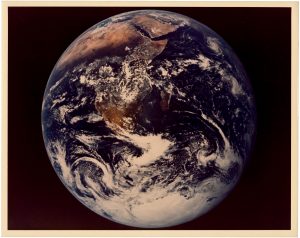

It sparkles and shines; it absorbs light, and it casts light back with a unique, effusive clarity. Water is omnipresent.

Wasserspiele

It sparkles and shines; it absorbs light, and it casts light back with a unique, effusive clarity. Water is omnipresent. On a planetary scale it overwhelms us – it fills our oceans, weighs down the air around, wears the earth beneath our feet down and away into plunging gorges and vast canyons, and coats that earth again in crystal ivory when the air and earth turn frozen. On the microscopic scale it finds its way everywhere, dissolving and diluting, breaking nutrients down and conducting them onwards to feed the cells of plants and animals.

This elemental blend of two parts hydrogen and one part oxygen serves as home for countless species of organisms, ranging from the largest to the smallest forms of life on the planet. Because water can hold and carry things both living and lifeless, its purity varies dramatically, along with its best possible uses from one source to another.

Evaporation of water acts a magic cleanser, leaving solid impurities behind as the pure moisture is drawn into the skies, re-gathered in clouds and re-distributed across earth and ocean with the help of global air currents and crashing storms. Water’s immense power is central to local, national, and international political scuffles and decision-making processes. It has molded and will only continue to mold geography both physical and political, and, with it, the history of human life. Social systems and customs are intimately bound up with the availability of water, and there is no economy on earth that does not leverage its value or suffer from its scarcity. The physical record of water’s changing impact over the centuries and millennia often are found concealed underwater, in soil, jungles, and caves, luring anthropologists, just as journalists and storytellers are drawn to the fascinations of fire, flood, and hurricane, and the opportunity to weave new tales from the devastation and prosperity water can bring. Its influence in language, music, art, theater, and ritual ceremony and custom is nearly endless – think of Sumidagawa in classical Noh theater, of the rain dances of indigenous cultures worldwide, of Moby Dick or Rusalka (or The Little Mermaid!).

Water is the fundamental shapeshifter. It reflects color, catches light, flows, and freezes. Even as it turns predator to the unwary, it becomes artistic prey for photographers, filmmakers, and painters, seeking to capture the fleeting, spellbinding truths it contains, casts back, and carries away.

Text adapted from: https://magazine.libarts.colostate.edu/article/water-as-science-and-art/

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

Franz Schubert - Gesang der Geister über den Wassern Article 'Aqua Depicta' Fallingwater M.A. Thesis 'The Ocean in Moby Dick' Water Encyclopedia NASA Blue Marble Collection Ocean Waves Sounds Handel - Watermusic Trick Fountains Hellabrunn Turner's Sketchbooks, Drawings, Watercolors

Digital technology has made the process of altering photographs faster and easier, more difficult to detect, and more accessible to more people – many more people – than at any point in history.

The Art of Airbrush

“I do not understand why this is supposed to interfere with the truth. … Photography is still a very new medium and everything is allowed and everything should be tried.”

(Bill Brandt, “A Statement,” (1970), in: Bill Brandt: Selected Texts and Bibliography,

ed. Nigel Warburton (Oxford: Clio Press, 1993), p. 31.)

Digital technology has made the process of altering photographs faster and easier, more difficult to detect, and more accessible to more people – many more people – than at any point in history. Its beginnings, though, stretch back far further than the late twentieth century and the advent of digital photography. Though the technology may be new, the desire to modify camera-captured images is as old as photography itself, and the determination of artists and inventors through the generations has brought new techniques and innovations at every step. Nearly every kind of photographic manipulation we now associate with Photoshop was once part of photography’s analog repertoire, from slimming waistlines and smoothing away wrinkles to replacing backgrounds and adding people to group shots (or, in other cases – removing them!). From the earliest days of photography onward, photographers have devised a staggering array of techniques, including multiple exposure, photomontage, combination printing, airbrush retouching, and more.

(Adapted from: Mia Fineman, Faking it. Manipulated Photography before Photoshop (New York: Metropolitan Museum, 2012), p. 5-6.)

Winston Smith, protagonist of George Orwell’s novel Nineteen Eighty-Four and civil servant in Oceania, the totalitarian superstate ruled by ‘the Party’ works in the Records Department of the Ministry of Truth, where he spends his days ‘rectifying’ historical documents to accord with the Party’s latest version of reality – falsifying the past to square it with the ideological needs of the present. One day, while rewriting a newspaper report concerning a speech by Big Brother, he invents a fictious war hero, Comrade Ogilvy, whose death the rectified speech will commemorate. “It was true that there was no such person as Comrade Ogilvy,” Winston reflects, “but a few lines of print and a couple of faked photographs would soon bring him into existence. […] Comrade Ogilvy, who had never existed in the present, now existed in the past, and when once the act of forgery was forgotten, he would exist just as authentically, and upon the same evidence, as Charlemagne and Julius Caesar.“

(George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), quoted in Mia Fineman, Faking it. Manipulated Photography before Photoshop (New York: Metropolitan Museum, 2012), p. 89.)

When Orwell was writing, in the late 1940s, the Stalinist project of historical revisionism was in full swing in the Soviet Union, and the faking of photographs was a key tactic in the regime’s systematic falsification of the past. A manipulated photograph could endow political fiction with an air of factual authenticity. The falsification of photographs was widespread in the Soviet Union, but it was hardly unique to that country or that political system. The temptation to ‘rectify’ photographic documents has proved irresistible to modern demagogues of all stripes, from Adolf Hitler to Mao Zedong to Joseph McCarthy.

In a relatively benign example discovered among the files of Hitler’s official photographer, Heinrich Hoffmann, Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels is excised from a publicity photograph taken at the Berlin home of filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl in 1937, possibly in order to combat rumors that Goebbels and Riefenstahl were having an affair.

(Adapted from: Mia Fineman, Faking it. Manipulated Photography before Photoshop (New York: Metropolitan Museum, 2012), p. 89-90.)

Airbrush:

Tool that combines a liquid medium with air and forces it through a tiny orifice to produce a fine mist for smooth application of the medium to a substrate. First patented by the American Francis E. Stanley in 1876 and used for coloring and coating photographs as well as for retouching, the airbrush was a precursor to aerosol spray paint.

(Adapted from: Mia Fineman, Faking it. Manipulated Photography before Photoshop (New York: Metropolitan Museum, 2012), p. 270.)

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

PhD Thesis on Airbrushing Airbrushinfo.net Blau Bulletin #1 (Retouching in Photography) Airbrushed From History (Article The Independent) How Politicians Are Retouching Their Photos Artists Working With Airbrush Barrie Cook (The Guardian) Digital Retouching of Skin with Airbrush

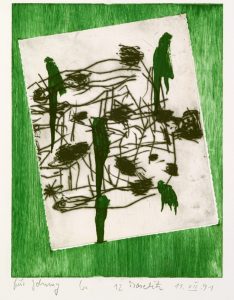

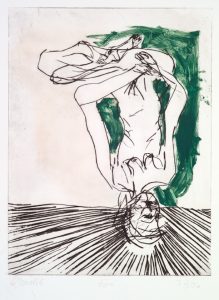

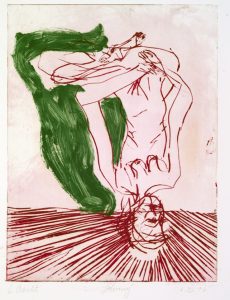

We associate green with Spring, with new birth and rebirth and plants as they sprout and grow.

Green

We associate green with Spring, with new birth and rebirth and plants as they sprout and grow. As the color of yearly renewal and of the triumph of spring over cold winter, green symbolizes hope and immortality. The very root of the word in German – ‘grün’ – lies in the old Germanic ‘ghro,’ whose meaning is fundamentally to grow and to thrive.

Nor, for that matter, is the relationship between the English words ‘grow’ and ‘green’ a coincidence. With the help of sunlight and carbon dioxide, which man and animal alike expel in breathing, the plants of the world are able to produce starch and the oxygen so necessary for our own life.

The magic ingredient in photosynthesis is the green pigment chlorophyll, which possesses the ability to transform inorganic substances into organic ones.

In ancient Egypt, the color green carried, along with blue, primarily positive connotations. The ancient Egyptian goddess of the sky (and of cows), Hathor, was portrayed on occasion in the form of a green tree. She was taken to be mistress of both love and life. Green malachite was of particular importance. The stone would be ground down and mixed with egg white, acacia resin, or fig sap to create emerald paints, used for instance by Egyptian women as eyeshadow. Along with its use as a pigment, it was, and remains today, a highly prized gemstone. The Egyptians mined the mineral on Mount Sinai, extracting copper from the ore. In the Arab world, pulverized malachite was taken as an antidote to poisons and to counter ulcers. The same was true of the gemstone emerald.

Green, in the Middle Ages, was the color of love, but not of love alone: evil serpents and demons were increasingly portrayed clad in or surrounded by green as well. In ancient China, dragons still possessed very positive meanings. They symbolized the divine power of transformation, the rhythm of nature, as well as supernatural wisdom and strength. In each instance, the positive symbolism of the dragon and the color green went hand-in-hand.

Christianity took the positive symbol of the dragon and turned it on its head, creating a monster from it, one that combined everything evil and destructive in it. The skin of Christian demons was colored green, like their eyes, and far from being bridges to divine wisdom they led their victims directly to hell.

Fertility’s association with the color green became a mark of shame as the guardians of Christian morality sought to avoid every hint of excessive sexuality. The Devil – in his style as hunter of souls – appeared in green clothing. Although many artists of the Middle Ages had painted Christ upon a green cross, and many saints in their paintings wore green themselves, as a symbol of hope, the idea that green and gold together indicate poison existed then and has endured to the present day. This association was so strong that it led to the term ‘venom-‘ or ‘poison-green.’

A truly poisonous ‘venom-green’ green actually does exist, though only since 1805, when chemists in the German city of Schweinfurt sought to create a paint more deep-green than what existed at the time. Its recipe calls for verdigris and arsenic acid. After application to, for instance, the walls of a room, moisture can still interact with the paint, resulting in a chemical reaction that produces toxic fumes of arsenic compounds. In German it is still called ‘Schweinfurt green’; ‘Paris green’ is the more common name in English, due to its later application as rat poison in Parisian sewers. Napoleon had a particular affection for the color green. The walls of his exilic room on St. Helena were painted in Paris green. When Italian chemists of our own century, a team from the University of Milano-Biocca, conducted a chemical analysis of Napoleon’s hair, they found elevated concentrations of arsenic in it. Theories erupted following the results’ publication, claiming that Napoleon died from arsenic poisoning. Following a more recent and more precise examination by the Milanese professor Ettore Fiorini, arsenic was determined not to have been the cause of Napoleon’s death. Evidently, the emperor had died of a stomach tumor.

Sources/Further Reading:

Adapted from: Thomas Seilnacht, “Naturwissenschaften unterrichten. Didaktik der Naturwissenschaft”, online: Sailnacht, “Phänomen Farbe. Grün”: Lexikon Grün

Robertson, D. W. “Why the Devil Wears Green.” Modern Language Notes, vol. 69, no. 7, 1954, pp. 470–472. JSTOR, JSTOR

Hutchings, John. “Folklore and Symbolism of Green.” Folklore, vol. 108, 1997, pp. 55–63. JSTOR,

Dorothee Fauth, “Kunstlexikon. Porträt,” June 2, 2005, for Hatje Cantz online:

JSTOR

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

Study 'Colors, Emotions, and the Auction Value of Paintings' R.E.M. Green Album (1988) Playlist Sing along 'Grün, grün, grün sind alle meine Kleider' Sing along '10 Green Bottles' Noteworthy Greens Guiseppe Verdi at the Met Verdi's 'Rigoletto' (full movie) 1982 starring Luciano Pavarotti Asteroid 'Green' Attenborough's Paradise Birds - BBC

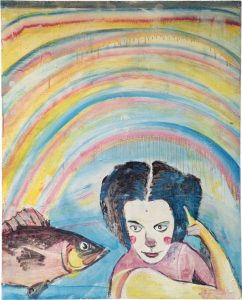

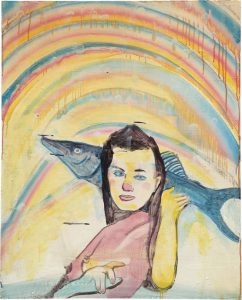

31 x 23 cm, © John Lurie, courtesy Daniel Blau, Munich

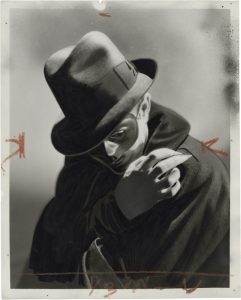

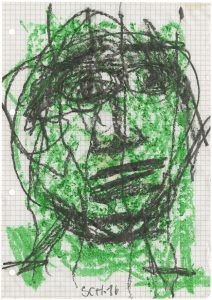

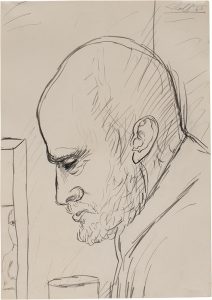

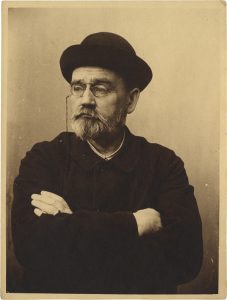

The portrayal of the human figure is one of the oldest themes and subjects in the entire history of artistic expression.

Me, Myself and I

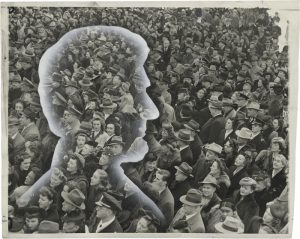

The portrayal of the human figure is one of the oldest themes and subjects in the entire history of artistic expression. As it became a more distinct genre, the portrait as such took over many of the roles and functions of those early human images, such as a certain immortalization of the subject after death, representative duties and deputized purposes in lieu of the subject himself. Portraiture experienced its heyday from the late Middle Ages through to the 17th century. This was in stark contrast to the era of early Christianity, which, on account of the young religion’s adamant rejection of potentially idolatrous representative art, knew very little in the way of individual likenesses and portraits.

The history of the portrait begins at the moment when the ambition of artist turns towards making resemblance the main subject of their artwork. Resemblance had been understood since the late 15th century to be not only a matter of external appearance, but also one of inner essence and being. While portraits of the late Middle Ages were overwhelmingly formulaic, a new development in painting began to take hold after 1300, according to which the identifiable features and physical characteristics of one particular human subject were mixed with images and allusions from the overall canon of sacred, mythological, and historical subjects and themes. The lords and patrons were the first faces recognizable in the painting, but their presence still had to be legitimized by the portrayal of an accompanying saint.

It was only much later, with the beginning of the Renaissance and the era’s new understanding of Man as an autonomous individual, that the portrait came to conquer the private sphere and an emerging middle class. Toward the end of the Quattrocento the psychological ‘moment’ came into view, which naturally cannot be understood in the modern sense. The essence of a person, his mental state and emotional psychology, wasn’t achieved through any sort of analytical carving away, but was betrayed instead through subtle means. The fact that a portrait always, by definition, transcends the status of an exact one-to-one snapshot, but is rather always an aesthetic construct, is due to the desire of those portrayed to tell the world something about themselves. Merits, virtues, values, education, status and position in society are thereby hidden, in and by means of symbols and symbolisms – in attributes, interiors, landscapes, clothing, and posture.

It was at this same historical moment that self-portraiture began its ascendance to the prominent position it occupies today in the portrait-painting tradition. It served, on the one hand, a personal purpose for the artist himself, a place for private experimenting, and on the other hand can be understood in a broader social sense as one expression of burgeoning self-confidence in the individual. After all, as the role of painter as artist came to be held in greater and greater esteem over the course of the Renaissance, so rose as well the worth of his own image – an image at first half-hidden in larger compositions, gradually growing to be a stand-alone portrait in its own right.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, portraiture reached its zenith. The portrait has now finally arrived in the both the civic and private realm. Much was to change from the 19th century onwards: with the advent of photography, a quick and convenient technology came onto the market, one which created an image where reality and recreation were nearly identical.

The painters of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, in turn, shook the mainstream artistic world by finally and forcefully separating color and shape from one another. Painting triumphed over visually perceived reality. With advances in photography, new demands were placed on portrait painting, ones which inevitably drew further and further away from the artistic and practical demands being met by technology-based forms of visual reproduction.

Mummy Portraits

The earliest movable portraits have their origins at about the time of Christ’s birth, from the Faiyum, a lowland oasis region lying some three hundred kilometers south of Alexandria. Egypt had only recently been annexed by the Romans, a change in jurisdictional fortune that relegated it to the outskirts of an empire based across the Mediterranean Sea. Roman mercenaries, given leave to become farmers, were settled in the distant province, becoming in the process the foundation of a new, hybrid culture in the Faiyum.

The ancient belief that the deities humans worshiped were bound to one particular place belonged just as much to the Egyptians as it did to the Romans. The mercenaries settled in the Faiyum, therefore, had Egyptian gods to worship. The gods of the Egyptian countryside were, for them, simply different manifestations of the true gods; the Egyptian Amon and the Hellenic Zeus were one and the same person, just as Osiris, Bacchus and Dionysus were. Through the cult of Osiris, however, the Egyptian belief in an afterlife, and its associated burial practices, found its way into the Roman colonies. One such practice was the ancient Egyptian custom of giving human form to the coffins of mummies, or attaching a mask, in the form of an idealized human face, to the coffin’s head, a custom which the Romans of Egypt adopted and modified.

A longstanding practice common among the upper classes of the Roman Empire’s more central provinces was the creation of individualized sculptural portrait busts, for exhibition in a household’s atrium or central courtyard. Just how much of a role that tradition played in the evolution of Faiyum portraiture can be debated; certain similarities, though, seem too striking to ignore. The mummy portraits of Roman Faiyum were painted in encaustic or tempera, on canvas or wood, unlike the earlier Egyptian practice of painting directly onto the sarcophagus, or even the bandages of the mummy itself; moreover, these were individualized portrayals of the deceased, not the standardized representation of a canonical set of human forms as indigenous mummy painting had been. This made them eligible as objects of display, an echo of the portrait busts of ‘home.’ A mummy portrait would be made during its subject’s lifetime, ‘living’ with him in his house until, after the subject’s death, it was wrapped in the mummy’s outermost bandages, at the head, something like a face, peering out from between the strips of linen.

There have been numerous mummy portraits found of children, appearing in their likeness very much alive; considering how unlikely it is that these would have been made during the lifetimes of their young subjects, we can assume that it was acceptable to create these portraits even when the sitter could no longer hold his own pose, at the very least in the case of an early or unexpected death. While that may seem a tad macabre, the practice is nearer to us than we might imagine; the modern age has passed down daguerreotypes and even photographs to us of children and babies who have already died, propped up before the lens to appear as among the living one last time.

source: G. Möller. “Das Mumienporträt,” Wasmuths Kunsthefte, Band I, Berlin o.J.

Mugshots

The word ‘mugshot’ is an informal term used describe an official photo taken of suspects in the course of police investigations. The photos serve as a tool to aid in identifying the perpetrator and can be used in the course of ongoing manhunts or criminal trials. In the USA, mugshots enter the public domain immediately, available to everyone through the Freedom of Information Act. The police usually take two mugshots at the time of arrest: one frontal, and one in profile. It is no longer common for the subject to hold a blackboard with his personal information on it, due to advances in digital photography and data recording.

Selfies

When someone takes a selfie, they are turning themselves into art. This is not quite the same thing as simply making a picture of oneself – that is, of making a self-portrait. To take a selfie means to take a picture of yourself in which and for which you are already transformed into art. A selfie is, then, in actual fact an image of an image.

The most pointed criticism of selfies distinguishes these from other categories of image, and from self-portraiture in particular. Indeed, although we might identify certain painters throughout history whose choice of themselves as primary subject aroused suspicion, the creation of self-portraits as such was never wholescale condemned as a vice, nor did any meaningful (and critical) discourse around the topic exist. An explanation might be found in the small number of artists who painted self-portraits in the first place; for reasons of sheer quantity (or lack thereof), self-portraiture as a genre or practice could not be fraught with many societal consequences. Perhaps, though, the particular circumstance of the selfie, the essence of its creation, plays a role as well – namely, that whereas a self-portrait is only an image one creates with himself as subject, the selfie must go further, is an image taken of a person already in the act of making himself into an image, into art, to be reproduced in the final image we call ‘selfie.’

Sources:

Wolfgang Ullrich, “Selfies. Die Rückkehr des öffentlichen Lebens”, Verlag Klaus Wagenbach, Berlin, 2019.

G. Möller. “Das Mumienporträt,” Wasmuths Kunsthefte, Band I, Berlin o.J.

Dorothee Fauth, “Kunstlexikon. Porträt,” June 2, 2005, for Hatje Cantz online:

Kunstlexikon Portrait

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

Mummy Portraits Podcast Mummy Portraits 24 Very Early Selfies How Artists Explore Identity by MoMA Selfportraits by Arnold Schoenberg Selfportraits by Schirn Kunsthalle Virtual Tour Egyptian Museum Munich Hieroglyph course (in German) The Art of the Selfie Self Portrait van Gogh

(from a photograph of a Daguerrotype by an unidentified artist), 7,1 x 8,8 cm, © Daniel Blau, Munich

+49 89 29 73 42

+49 89 29 73 42