Month: November 2020

GEORG KOPPMANN

Vintage Photographs of Historic Hamburg

Architecture & Photography

Nineteenth-century German photography is represented only by a small number of photographers, who appeared to have worked mainly in Italy. They were fascinated by the great wealth of the Italian architecture and by the antiquities found nearly everywhere in the country. This makes Georg Koppmann’s photographs that much more noteworthy, documenting as they do not only a Hamburg which no longer exists, but a moment in the history of photography, artifacts and historical studies in and of themselves. These photographs are a valuable source of knowledge for a great city’s architecture, both as documentation and representation.

From the very beginning, photographers have explored architecture as a primary subject. One of the first surviving photographs takes an architectural theme, a view captured by Joseph-Nicéphore Niépce in 1827, across the rooftops of his property. When the printing process was further improved following the collaboration between Niépce and Daguerre, albums could be published, bearing photographs of the world’s great monuments in Egypt, Nubia, Palestine and Syria, in Greece, Spain, Italy and France. William Henry Fox Talbot’s earliest surviving photograph has an architectural subject, too.

Drawings offer a useful source of information about architecture, allowing us to peer over an architect’s shoulder, and, thus, making it possible to trace the design and development of a building. Photographs, however, provide an immediacy and accuracy of representation. Talbot – considered the inventor of the negative process – wrote in 1845 that “even accomplished artists now avail themselves of an invention which delineates in a few moments the almost endless details… which a whole day would hardly suffice to draw correctly in the ordinary manner.”

Photographers also were commissioned by municipal and private agencies to document old buildings on the cusp of demolition, in urbanization and modernization’s path. The systematic documentation of Paris by Charles Marville shows whole streets and neighbourhoods being destroyed as entirely new areas of the city are developed in their place. Georg Koppmann’s photographs show historic streets, buildings, canals and bridges of Hamburg just before they were torn down for the imminent construction of the city’s famed warehouse district – the Speicherstadt.

Speicherstadt

Speicherstadt (“Warehouse District”) is the world’s largest complex of warehouses, with an area of 260,000 square metres. It was built into the Elbe River between 1883 and the late 1920s, on thousands of pilons, as a free economic zone in Hamburg’s port. In 2015, Speicherstadt, Kontorhausviertel and Chilehaus became Germany’s 40th UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg became part of the German Empire in 1871, but for a time it was able to maintain its own tax and customs regulations. This privilege remained in place until 1881, when a new customs union was installed. From this point on, only the free port area along the Elbe River remained exempt from import sales taxes and customs. Final annexation of Hamburg by the German Empire was scheduled for 1888, allowing the city seven years to create new storage facilities inside the free port area. In order for construction of the warehouses to begin, which it did in 1883, around 24,000 people had to be evicted, and around 1,100 houses torn down.

In 1888, Emperor Wilhelm II inaugurated Speicherstadt, although only the first building phase had been completed. Interrupted by World War I, construction lasted all the way until 1927. During World War II, Operation Gomorrha destroyed the western part of the district. Reconstructions lasted until 1967. Finally, on January 1, 2013, an era came to a close, and the free economic zone of Speicherstadt, covering almost a fifth of the area of Hamburg’s entire port, was dissolved.

sources:

Richard Pare, Photography and Architecture: 1839-1939, Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal 1982. www.hamburg.com

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Find all exhibited images here

Other Diversion

'3 Hamburger Frauen' Artist Collective Georg Koppmann Prize Hamburg

Georg Koppmann (1842-1909)

In addition owning a photography business in Hamburg, Georg Koppmann made a name for himself through his work as a photographer in his own right, and especially for the photographs he made of architecture and cityscapes throughout Germany. On behalf of the Hamburgische Baudeputation (Hamburg Building Deputation), he photographically documented the streets and buildings that would have to be cleared for the construction of Speicherstadt from 1883. This work was published in the portfolios “Hamburg 1883 ‘Ansichten aus dem niederzulegenden Stadttheil'”, with 35 albumen prints, and “Hamburg 1884 ‘Ansichten aus dem niederzulegenden Stadttheil'”, consisting of 36 albumen prints.

Rudolph Brandt (1910-1982)

Rudolph Brandt was born on December 4, 1910 in a small Jewish village called Vereski, in the countryside outside of Prague. He was the oldest of five children. He was born Yosef Goldberger, into a prominent rabbinic family. His paternal grandfather, was a renown rabbi, a tzadik. People would come from all across Europe to consult with him, resolve legal disputes, and seek his blessing. His father, also a rabbi, served as a chaplain in the Austro-Hungarian army. His maternal grandfather was a prosperous merchant. He owned a general store which also served as the Royal Hungarian, and later, the Czech custom house. Yosef grew up speaking Hungarian, Czech, and Yiddish. He was fluent in all three languages. He also studied Hebrew as it was assumed that he would follow in the tradition of his family and become a rabbi. As a child, he studied the Hebrew Bible, the Talmud and the teachings of the rabbinic commentators.

Yosef also studied in the gymnasium, where he learned French and German. By 1929,he had left his family home and traveled across Europe, working as a tour guide and translator. Unable to receive a Czech passport without first serving in the Army and following an intention to shed his Jewish identity, in a small cafe near Metro Saint Paul in Paris, Yosef bought a German passport and an identity card. On that day, with the exchange of 300 francs, Rudolph Brandt was born. In 1931, Rudolph traveled from London to Tampico, Mexico. The boat, which carried him to Mexico was designed to carry freight and 30 passengers. It was packed with over 250 Jews from across Europe. The passage took 30 days.

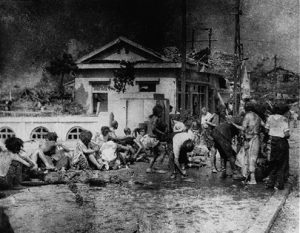

In Mexico, Rudolph taught himself Spanish and became a salesman, traveling throughout the Mexican interior selling shoes, dresses, toothpaste and brushes. After a year, he settled in Mexico City and became a liquor merchant. Throughout his childhood, the United States had a great lure for Rudolph. He heard stories of the great opportunities in America. In late 1932, he illegally crossed into the United States from Laredo, Mexico. He traveled around the United States, living briefly in New York, Los Angeles, and Oklahoma City. Over the next years, an adventurous and restless Brandt, left the United States and traveled through Mexico, South America, and Europe. In 1937, Brandt found himself in Shanghai, where he witnessed the first Sino-Japanese incident. It was in Shanghai that Brandt established himself as a photo-journalist and was hired by United Press International (UPI) to produce a pictorial report of the Sino-Japanese War. There he befriended the Far East Manager of the UPI, John R. Morris, and worked for him for two years, covering the bombings in Shanghai and traveling north toward Peking to photograph the army of General Mao Tse-tung. Next Brandt traveled to Nanking to photograph what became known as “the rape of Nanking” and then returned to Shanghai via Canton. From Shanghai, he traveled to Singapore, where he photographed for “The Straight Times Annual”, and then to Manila, where he pursued advertising and commercial photography. In the early 1940’s, Brandt returned to the United States. He settled in Berkeley, California and landed a job as a photographer with the San Francisco Examiner, working for the manager of the city desk, Josh Eppinger.

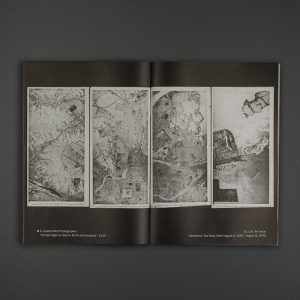

With the outbreak of World War 2 on December 7, 1941, Brandt was arrested as a suspected spy and interred for a time at Terminal Island and McNeil Island, where he was detained with Japanese Americans. In 1943, cleared of all charges, Brandt volunteered to serve in the United States Armed Forces. He was assigned to the Army Air Corp and was dispatched to the Pacific theater of operations, where he photographed Japanese naval activities. Brandt completed his military service in 1946 and landed a position in the training section of the United States Veteran’s Administration. Through this work, he became interested in psychology and enrolled in the University of Southern California where he received a Master’s in Psychology. Brandt received a Doctor in Psychology from the University of Ottawa and subsequently studied under Oscar Phister in Switzerland and became a Psychoanalyst. He returned to Los Angeles where he established a successful private practice. Throughout the 1960s and 70s, Brandt was active in psychoanalytic circles. A fellow in numerous professional societies, he directed the Melrose School for Emotionally Disturbed Children, stared in a weekly television show, Dr. Brandt’s Cable Couch, served as a member of the State of California Board of Medical Examiners and as visiting Professor at the University of California. Brandt volunteered for numerous civic organizations.

Though his professional career as a photographer ended with the close of World War 2, he continued to take photographs throughout his life, and maintained a color darkroom in his home in Los Angeles.

Rudolph Brandt was married to Suzanne Brandt, and had two children. He died on January 27, 1982 at the age of 72 . Rudolph is survived by his two children and four grandchildren, including his namesake, granddaughter Rudy Brandt.

See our publication “1937 Japan Attacks China!”

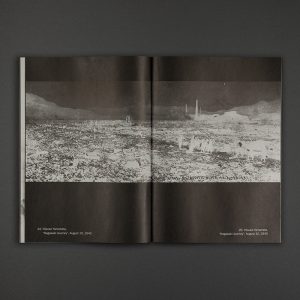

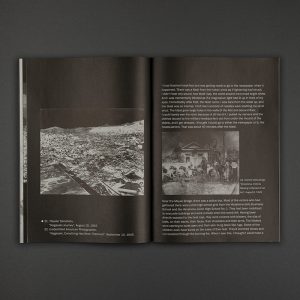

Yoshito Matsushige

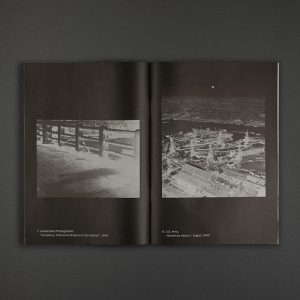

Yoshito Matsushige (1913-2005) was born in Kure, Hiroshima. As a photojournalist, he took five photographs on August 6, 1945, the day of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. At the time of the explosion, Matsushige was at home, 2.7 km south of the hypocentre. He is the only person to have captured an immediate, first-hand photographic account of the bombing. Matsushige dedicated most of the rest of his life to organizing and preserving the photographic history of the atomic bombing of his hometown.

Hiromichi Matsuda

Hiromichi Matsuda (1900-1969) was working as a photographic technician at Kawanami Shipyard when the “Fat Man” atomic bomb hit Nagasaki on August 9, 1945. He took photographs of the mushroom cloud from the rooftop of the shipyard office and from ground level outside about ten minutes after the bombing.

Torahiko Ogawa

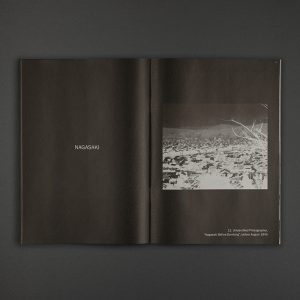

Torahiko Ogawa (1890-1960) was born in Tsukihi, Tokyo. After graduating from the Tokyo Photography Academy, he opened a studio in Nagasaki. At the request of the Nagasaki Prefecture, he photographed the devastated city between August 20 and September 30, 1945, and again in June 1946.

Yosuke Yamahata

Yosuke Yamahata (1917-1966) worked for the Japanese News and Information Bureau. The day after Nagasaki was destroyed by the atomic bomb, he was assigned to the Bureau’s Army division and sent to the city to document the fallout. Only a few photographs were published before a press ban was imposed. After the ban was lifted in 1952, Yamahata published his photographs in Atomized Nagasaki: The Bombing of Nagasaki – A Photographic Record.

See our publication “X-Ray Japan 1945”

X-Ray Japan 1945

DANIEL BLAU has established himself as a necessary name in historical photography. With Misled: German Youth 1933-1945 and 1937 – Japan Attacks China!, Blau has assembled two collections of documentary photographs from some of the darkest moments in modern history, making many of them accessible and available for the first time, after over 70 years of existence. {…}

{…}Accordingly, the presentation in this pamphlet might also be taken as neutralizing, whetting our gaze as viewers to the artistic and aesthetic aspects of the recordings without dulling thereby our knowledge of the historical and human background. In this way, the photographs insist as well upon their significance for history. We only recognize that which we have seen with our own eyes as the undisputed truth, a truth cradled forward by the time capsule of historical photography.

With all this in mind, we might treat this pamphlet as a chance to explore the complex perspectives one can take without losing sight of what took place or of photography as a document of wartime reportage. Considering how little time elapsed between Yamahata taking his pictures and creating the prints exhibited here, these prints bear an aura of historical event about their very selves, and create a special sense of closeness that modern prints couldn’t approach. The stamps and slugs, often printed and applied to the back of the photos, facilitate an intuitive chronological classification and bring us closer to the historic moments and destinies lying behind them; they act in this sense both as objects of their time and as links between 1945 and 2020, between photographer and viewer.

What’s more, the extensive compilation of Japanese and American photographs offers a chance for us to construct a more fully realized image and understanding of August 1945. Perhaps we should speak of the curator here as taking on the role of intermediary, offering these images in terms and frames necessary for audiences to grasp them fully, grapple with their implications and wide range of interpretations, and to see them as they were first seen through the photographer’s lens and in the spirit he hoped they would carry with them. “Today,” he wrote years later, “with the remarkable recovery made by both Nagasaki and Hiroshima, it may be difficult to recall the past, but these photographs will continue to provide us with an unwavering testimony to the realities of that time.”

Text: Katharina Rohmeder

Printed and bound by Pelo-Druck Lohner oHG

Paper content: Offset 50g/m2

Paper cover: Olin, Rough, cream, 200g/m2

Published: 2020

64 pages, 33 images

15×21 cm, softcover

ISBN: 978-3-9821983-2-3

Editor: Daniel Blau

Text: Katharina Rohmeder

Editor: Robert Isaf

Layout: Christiane Wunsch

Order your copy here

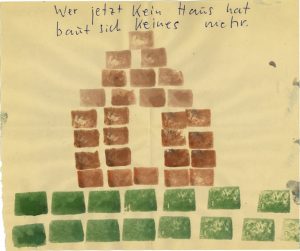

Housing Projects by Lüpertz, Kiefer and Immendorff

Architecture & Art

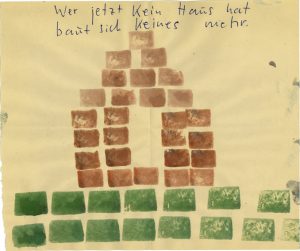

The painting career of Markus Lüpertz (b. 1941) begins with the discovery of the “Dithyramb” – a term from the poetics of the antique world, originally denoting a form of song in praise of Dionysus, God of Wine, and which has come in common parlance to describe an attitude of exuberance towards life, of a passionate ‘inspiration’ and ‘drunkenness.’ The post-war period was marked by a hesitant and even over-cautious restraint, which over time began giving way to a taste for strength and dynamic drive in art. Lüpertz’s decisive artistic disassociation from the environment around his applied arts school in Krefeld, and the beginning of the Dithyramb, belongs precisely to this moment in history. The interpretation of the Dithyramb as an architectural idea, as a house of diverse materials and parts, stems from a series of linear Dithyramb constructions in chalk dating to 1964, a series including the sheet shown here. Building blocks, shadowed all around in blue and white, form themselves into a grid, which itself is fractured and inserted into flat tiles. A new possibility begins to hint at itself, the possibility of releasing shape and form into the third dimension.

After an absence of several years, Anselm Kiefer (b. 1945) first returned to the public eye in 1973 with a series of pieces containing references from the bible, Germanic mythology, and the literary canon. These works are – as is characteristic of his entire oeuvre – inscribed with descriptions, names, and quotes.

“I view my pictures as ruins, or like building blocks, things which can be put together. They are the material with which you can build something, but they are not complete. They are closer to that which does not exist than they are to that which is completed.” – Anselm Kiefer.

The neo-Dadaist project “LIDL,” created by Jörg Immendorff (1945-2007) and Chris Reinecke, set out with the goal of bringing art and politics together in a tangible way, attempting to make alternative, artistic concepts accessible to a public outside of and with limited engagement with the prevailing currents of the world of art. In 1968 Immendorff designed a minimalistic concept for his “LIDL”-city: little houses of wood and packaging paper, within which the “LIDL”-commune would live. The “LIDL”-Academy is among the most famous actions taken as a part of the artist’s early “LIDL” period. Immendorff and some kindred spirits declared it open within the Dusseldorf Art Academy on December 2, 1968, in the wake of a row that had broken out regarding an open letter published by ten professors which accused Joseph Beuys of seeking to use the German Student Party (which he helped to found) as a tool to exert influence over the Academy’s curriculum.

sources:

Siegfried Gohr, Markus Lüpertz. Zeichnungen aus den Jahren 1964-1982. Ausgewählt von Siegfried Gohr und Johannes Gachnang, Bern/Berlin 1986.

Josef-Haubrich-Kunsthalle Köln, Markus Lüpertz. Gemälde und Handzeichnungen 1964-1979, Ausstellung 01.12.1979-13.01.1980.

Theo Kneubühler. Anselm Kiefer, in: Kunsthalle Bern, Anselm Kiefer. Bilder und Bücher. Ausstellung 07.10.-19.11.1978.

Toni Stooss, Des Malers Atelier, in: Götz Adriani, Anselm Kiefer. Bücher 1969-1990, Tübingen/München/Zürich 1990-91, S. 24-33.

Kunsthaus Zürich, Jörg Immendorf, Immendorf, Ausstellung 19.11.1983-22.01.1984, Zürich 1983.

art Magazin 07/2001: art-magazin.de

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

+49 89 29 73 42

+49 89 29 73 42