Category: BULLETIN

BULLETIN

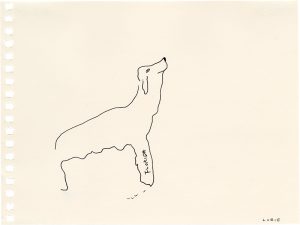

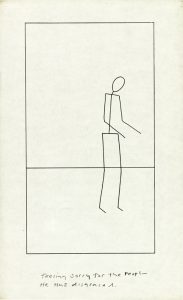

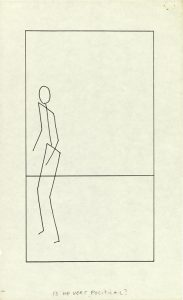

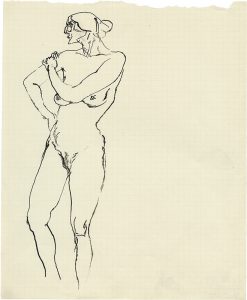

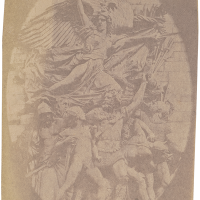

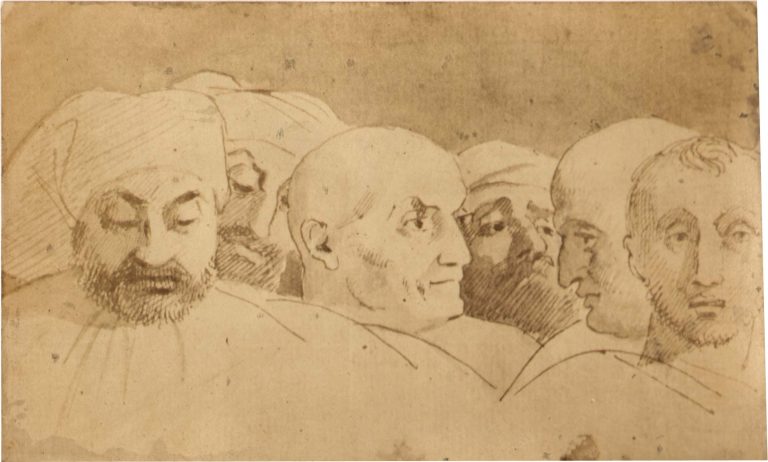

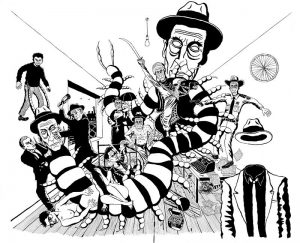

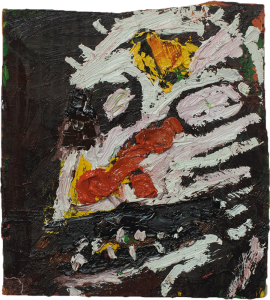

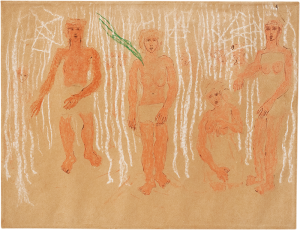

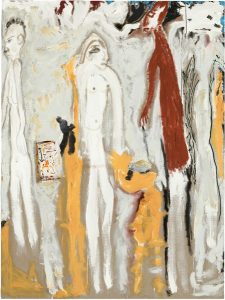

In the history of art, the simple line drawn has always held a position of fundamental importance.

The Fine Line

The Fine Line

In the history of art, the simple line drawn has always held a position of fundamental importance. The earliest ‘artworks’ still available to us today are prehistoric engravings in caves, which, using only the simplest means – in only a few lines – clearly show man and animal, weapon and tool, distinguishable even today by their distinctive and characteristic contours. A high-water mark in the importance of line-based drawing – il disegno – can be found in the theoretical debates that raged through the world of Italian art in the years after the Florentine Academy was founded, debates whose central theme was the matter of whether il disegno played a more essential role in artistic creation than the shading and tonality embodied by the concept of Venetian colorito. The Paragone, the debate of the academies between contour and color, carried on through the centuries until it reached another zenith with the Poussinists and Rubenists. (1)

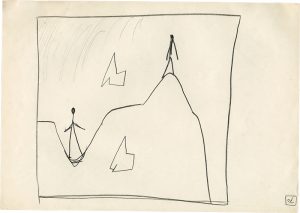

According to art historians and critics of the 20th century, ‘the stroke’ – or ‘the line’ – incorporates the entirety of an artist’s personal drawing style, both its conscious and unconscious characteristics. (2) The line sketches the contours of a shape only in certain regards – “the essentials are marked out, and everything else falls away.” (3) This conception of the line harks back to Leonardo da Vinci, himself of the convinced opinion that no true ‘Line’ in artistic terms exists in nature (4), and that what we conceive of as such is instead the abstraction of those shapes that are at hand and visible around us. “Lines confine and connect, characterize and accentuate.” (5) The line is a symbol, an attempt to make reality visible and comprehensible, but not an immediate, unadulterated imitation itself.

Delacroix, for example, in a letter dated the 15th of July, 1849, presents his own perspective on the matter. He positions himself in opposition to the idea that line and beauty have some sort of fundamental linkage, an idea that had enjoyed widespread currency among artists since the 18th century. “That often-discussed Beauty, which one fellow might see in a serpentine line, and another in a straight one – they’re both insisting on seeing nothing but lines. I stand at my window and behold a miraculous landscape, but the thought of a line never once crosses my mind. A lark sings, the river sparkles as though it’s made of a thousand diamonds, the leaves whisper; where are the lines, that can reflect such delightful impressions?” (6)

The art historian and author Julius Meier-Graefe (1867-1935) accused his art-creating contemporaries of “babbling on about the line the same way Xenephon’s Greeks once did about the sea,” (7) although he himself had played a large part in popularizing the line-focused aesthetic. (8) Around 1900, enthusiasm for the line increased again, and in all expressions of aesthetic production, in literature and architecture just as much as in the visual arts. It was now understood primarily as a moving element, and artists experimented with it accordingly. Kandinsky’s 1926 Bauhaus textbook “Point and Line to Plane” created a theoretical approach to the expression of different types of line, from a phenomenological perspective. He differentiates between degree of curvature, line variation, and their alignment on the plane. (9)

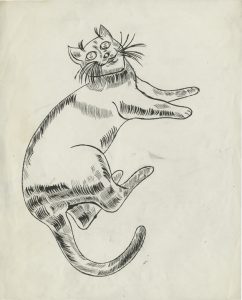

Moreover, it is impossible for a line to exist as nothing more than the outline of a shape alone. The variations between thick and thin, subtle and bold, intersecting and parallel, segmented and sweeping, confidently and haltingly drawn, all serve to impart to audience a feeling, a sensation, that goes far beyond the realm of the purely visible. The artist has other tools and techniques at his or her disposal, such as hatching, that can serve to make those sensations, and the visual cues invoking those sensations, even stronger; the result may very well be more along the lines of a sketched abstraction, or a symbol only indicating or standing in for a natural form, rather than something recognizable as a direct and intentional representation of objective reality. By overcrowding and overlapping lines over line, hatching, for instance, is able to convey a sense of plasticity and drama to the viewer, even though, strictly speaking, it remains only a distant reproduction of the shading that occurs in reality. (10)

sources:

(1) Matteo Burioni, Sabine Feser (ed.), “Giorgio Vasari. Kunsttheorie und Kunstgeschichte. Eine Einführung in die Lebensbeschreibungen berühmter Künstler anhand der Proemien”, Berlin 2004, p. 193-196, 229-231

(2) Uwe Westfehling, “Meisterzeichnungen von Leonardo bis zu Rodin”, Cologne 1986, p. 16

(3) Westfehling, p. 16

(4) Walter Koschatzky, “Die Kunst der Zeichnung, Technik, Geschichte, Meisterwerke, Munich 1981, p. 29

(5) Westfehling, p. 17

(6) Kurt Badt, “Eugène Delacroix. Zeichnungen. Eine Einführung auf Grund der Tagebücher des Künstlers”, in: “Eugène Delacroix. Werke und Ideale. Drei Abhandlungen”, Cologne 1965, p. 32

(7) Julius Meier-Graefe, “Entwicklungsgeschichte der Modernen Kunst. Vergleichende Betrachtungen der bildenden Künste, als Beitrag zu einer neuen Ästhetik”, Stuttgart 1904 (new edition by Hans Belting), Munich 1987, Bd. 2, p. 681

(8) Sabine Mainberger, “Experiment Linie. Künste und ihre Wissenschaften um 1900”, Berlin 2010, p. 7-8

(9) Raphael Rosenberg, “Die Linie in der ästhetischen Theorie des 18. und 19. Jahrhunderts”, in: Erich Franz (ed.), “Freiheit der Linie. Von Obrist und dem Jugendstil zu Marc, Klee und Kirchner”, Münster 2007, p. 12, after Beate Kemfert (ed.), “Linie und Skulptur im Dialog. Rodin, Giacometti, Modgliani. Werke aus der Sammlung Kasser/Mochary Family Foundation USA”, Munich 2011

(10) Westfehling, p. 17

All artworks are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

Johnny Cash, ' I walk the line', 1958 Petroglyphs within the Archaeological Landscape of Tamgaly Neanderthal artists made oldest-known cave paintings 45,000-Year-Old Pig Painting in Indonesia May Be Oldest Known Animal Art The Paper Side of Art Flatland - A romance of many dimensions Punkt, Punkt, Komma, Strich-- (Zeichenstunden für Kinder)

I SET TO WORK LIKE MANY OTHERS, AND SINCE THAT TIME I HAVE NOT STOPPED THINKING

ABOUT OR PRACTICING THIS NEW ART FORM.

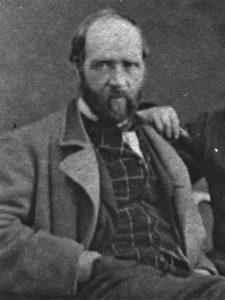

Louis Alphonse Poitevin

“JE ME MIS Á L’ŒUVRE COMME TANT D’AUTRES, ET, DEPUIS CETTE ÉPOQUE, JE N’AI PAS CESSÉ, SOIT D’IMAGINATION, SOIT MANUELLEMENT, DE M’OCCUPER DU NOUVEL ART.”

“I SET TO WORK LIKE MANY OTHERS, AND SINCE THAT TIME I HAVE NOT STOPPED THINKING ABOUT OR PRACTICING THIS NEW ART FORM.”

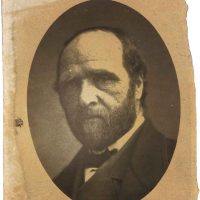

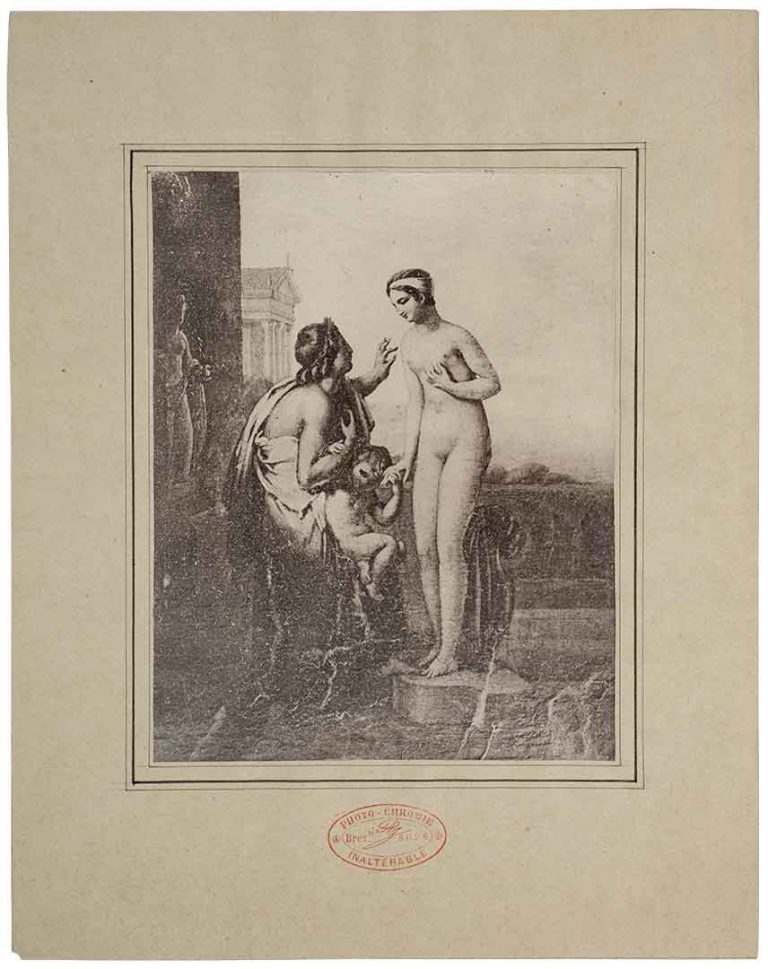

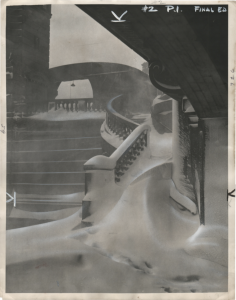

Alphonse Poitevin (1819-1882) was a chemical engineer who spent 35 years experimenting with photographic chemistry and photomechanical printing. A pioneer of photography’s earliest days, his first images were created with the techniques of his immediate predecessors: daguerreotypes, paper negatives and salted paper prints. However, as a chemist, he was also an inquisitive inventor eager to discover new photographic and photomechanical methods.

Today, Poitevin is remembered most for establishing the fundamental principles of four non-silver process families: photolithography, collotype, dichromate relief system, and the carbon pigment process. His inventions refined existing techniques and made the mechanical reproducation of images and thus, the illustration of printed books, possible.

Photolithograph, 1856 – 1857

Poitevin was the first to coat a lithographic stone with an albumen layer that had been rendered light-sensitive with dichromate salts. Following exposure to a negative, the entire surface was coated in printer’s ink, then washed in water, with the effect that the unexposed, and therefore unhardened areas would absorb water and cause the greasy ink to detach, whereas the ink remained attached to the surface in the exposed, hardened areas. After drying, the stone could be used for producing multiple lithographic prints in the usual manner.

Salted paper process, used by Poitevin ca. 1840 – 1850

Invented by William Henry Fox Talbot in 1840, this positive print process quickly gained popularity in England and France. A sheet of good-quality writing paper was dipped into a table salt solution, dried, then brushed over with silver nitrate dissolved in water. As a result, light-sensitive silver chloride was formed in the paper fibres, and images could be printed out on the sheet. The print was typically fixed with a solution of sodium thiosulfate and often toned with a gold chloride solution to change the image hue from reddish brown to deep purple. Although toning also increased the stability of the print, salted paper prints have always been prone to discolouration and fading.

Albumen process, used by Poitevin ca. 1847 – 1855

The albumen print was the prevalent photographic paper from the 1850s until the 1890s. A thin sheet of paper was floated on a bath of egg white (albumen) that contained salts. It was then made light-sensitive with a solution of silver nitrate. The albumen formed a discrete layer on the paper surface, which gave the print a distinct gloss and a crisper and more saturated image than a salted paper print. Albumen prints were almost always gold-toned to enrich contrast and colour and to increase image stability.

Pigment process with ferric chloride and tartaric acid, single or double transfer, 1861 – 1868

Rendering midtones in a pigment print can only be achieved with a transfer step, so Poitevin’s second procédé au charbon was more complex. Poitevin also chose a different light-sensitive substance: ferric chloride and tartaric acid. This mixture was applied to a sheet of glass, then dried and exposed to a negative in sunlight, which rendered only the exposed areas slightly sticky. Pigment powder could then be padded onto the surface, where it adhered, thereby forming a visible image. For a single-transfer print, collodion was poured onto the plate, then transferred – image and all – to a sheet of paper, resulting in a mirrored final image. To remedy this situation, a subsequent second transfer could be performed, bringing the collodion film holding the image to yet another sheet of paper. Differentiating between the single and the doble transfer prints today can be challenging, since the orientation of the original negative is not known.

Sources:

Martin Jürgens, “The Photographic and Photomechanical Explorations of Alphonse Poitevin”, in: Daniel Blau (ed.), “Louis Alphonse Poitevin 1819-1882”, Hirmer Publishers, Munich 2021, p. 7-9

Martin Jürgens, “Biography”, in: Daniel Blau (ed.), “Louis Alphonse Poitevin 1819-1882”, Hirmer Publishers, Munich 2021, p. 79

Martin Jürgens, “Index to Plates”, in: Daniel Blau (ed.), “Louis Alphonse Poitevin 1819-1882”, Hirmer Publishers, Munich 2021, p. 52, 57, 64, 72

Publication “Louis Alphonse Poitevin”Order your copy of our latest publication here

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

Guided Tour: Rijksmuseum 'The Best of the Gallery of Honour' Paulo Coelho: The Alchemist Paulo Coelho: The Alchemist Audiobook Photolithography - Step by Step Salt Prints at Harvard University

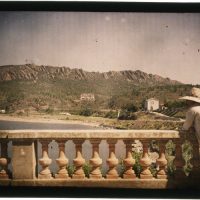

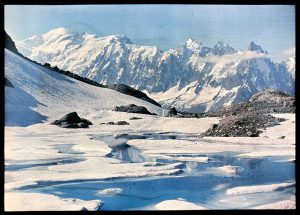

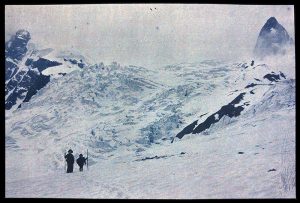

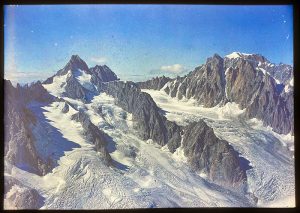

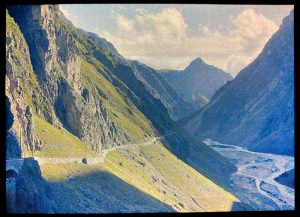

Glaciers are among the most beautiful natural wonders on Earth.

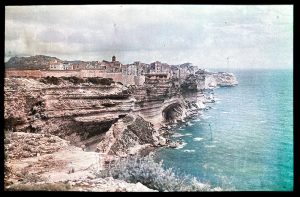

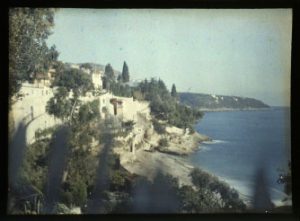

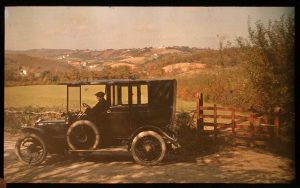

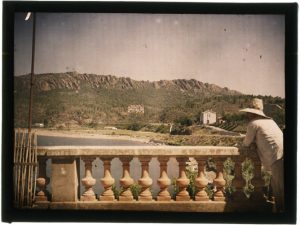

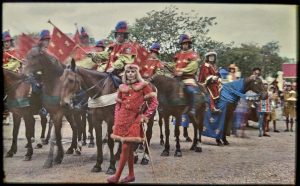

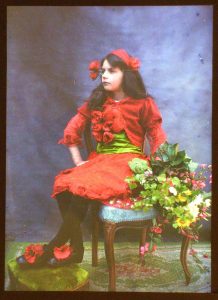

Traveling by Autochrome

Glaciers are among the most beautiful natural wonders on Earth. For most of us, though, they also remain deeply unknown and misunderstood. Glacial ice has shaped the landscape over millions of years by scouring away rocks, transporting and depositing debris far from its source. Glacial meltwater drives turbines and irrigates deserts, yielding mineral-rich soils and leaving us a wealth of valuable sand and gravel. Our future is bound up closely, if indirectly, with the future of glaciers, and with the impact of their fate on our global climate and sea levels.

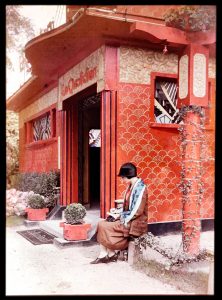

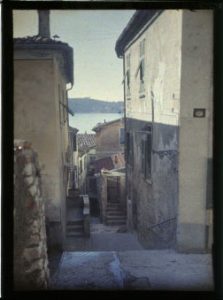

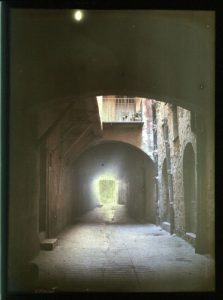

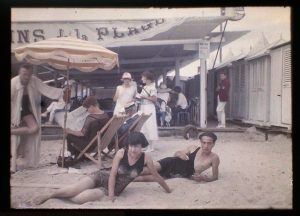

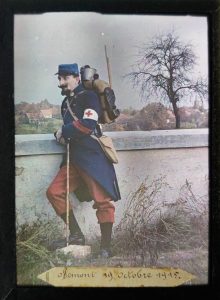

In 1914, a world’s fair was held in south of France – the Exposition international urbaine de Lyon.

The site of the fair sprawled across 184 acres of Lyon’s 7th arrondissement, including the grand Garnier exhibition hall, an imitation alpine village, a horticultural garden, a dedicated pavilion for the city’s famous silk industry, and international pavilions for both foreign nations and France’s overseas colonies. The last day was scheduled for November 1st, but history intervened. The outbreak of World War I forced the closure of the Austrian and German pavilions on August 2nd, and many of the fair’s other delegations left soon afterwards. The Exposition managed to remain open until November, as planned; by the time it officially ended, though, much of the once-proud fairgrounds had been empty for weeks.

Sources:

Sources:

Michael Hambrey, Jürg Alean, “Glaciers”, Cambridge University Press 2004.

Exposition international urbaine de Lyon

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

Before/after comparison photo of Rhone glacier (Valais, Swiss Alps) The Sound of a Glacier Guided Tour: Autochromes Franklin Knott All Episodes of 'Our Planet' with David Attenborough (Netflix) Lewis Dartnell: Origins Ben Day Dots defined

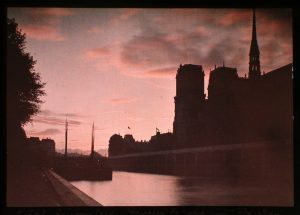

The Lumière Autochrome, invented and marketed by brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière,

was the world’s first practical color photography process.

The Art of the Autochrome

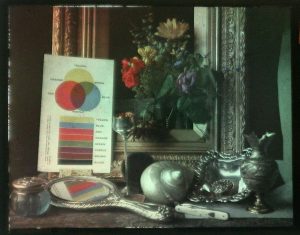

Even from the moment of photography’s invention, the absence of color was recognized as one of its greatest shortcomings. The development of color photography became one of photomechanical research’s primary goals over the course of the 19th century. The photosensitive material in use at the time did in fact register the wavelengths of different colors in our visible spectrum when recording an image – there simply wasn’t a way to directly reproduce that color. Once it was understood that a simple re-creation of color wouldn’t be possible, the technical pioneers and inventors of the time searched for another method, for a way to deconstruct the colors of reality and reassemble them again by scientific means.

The Lumière Autochrome, invented and marketed by brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière, was the world’s first practical color photography process. The trichrome (publicised a few years earlier) was the first commercially available color process. It was complicated to use, as three separate pictures had to be taken of the same object through different color filters. Thus the autochrome became the first practical color process. After ten years of intensive research and development, the Lumière company introduced the first autochrome plates in 1907. The color pictures that resulted were on glass plates, and viewed as transparencies. They consisted of a color screen superimposed upon a black-and-white positive, which modulated the light passing through the color screen. While more modern color techniques – even those which also resulted in transparencies as the final product – exclusively used subtractive color processes, the Autochrome stands apart for employing additive color.

We can narrow the use of Autochrome photography down to a relatively precise period of fifty years: from the commercialization of the process by the Lumière Brothers (1907) until the final end of the technology’s production (1956/57). Its importance, however, had already experienced a significant decline by the end of the 1920s. A turning point came in 1931, when Lumière replaced glass plates with celluloid sheet film (Filmcolor) as its commercially available capture medium. After 1936, Autochrome had to contend with competition in the form of subtractive color process, from Kodak (Kodachrome) and Agfa (Agfacolor), which began gradually replacing Autochrome plates on the market.

A glass plate would first be coated with tiny, transparent grains of potato starch that had been dyed in the additive primary colors – red, green, and blue. These dyed grains were mixed and spread in even proportions over the plate, which as a result appeared gray when white light was shined through. The spaces between the grains were filled by a carbon black dye. A final coat, of a black-and-white photographic emulsion, came on top of that. When the photographer placed the plate in the camera, this final coat of emulsion was furthest away from the lens; when the lens was opened, light had to pass through the glass plate and through the colored grains before reaching the emulsion, although it was this emulsion that we actually talk about as being ‘exposed.’

Instead of being processed as a normal black-and-white negative, the plate would be subjected to a procedure known as reversal processing: the negative is developed, the developed silver is bleached out before an image is permanently fixed, and finally any remaining silver salts are developed in turn, producing a positive image. Once the plate had been processed and dried, it could be viewed as a transparency, appearing as a photograph in full color.

The Autochrome worked because the positive image – even though monochromatic – acted to modulate the amount of light that went through each grain of dyed starch. In a red area of the picture, for example, a lot of light would have passed through the red grains onto the coating of black-and-white emulsion when the picture was taken. The positive was lightly shaded in that area, so a lot of light would also pass through the red grains when the final transparency was viewed. The green grains in that same area would have blocked the red light when the exposure was made; less light, therefore, would have reached the plate at that place, making that part of the positive darker as well, so that the green grains, when viewed later, were “turned off” by the heavy deposit of silver behind them. In controlling the intensity of the three additive primaries, the Autochrome worked exactly the same way as the modern television or computer screen.

The brightness range of the Autochrome was limited for two reasons: the black matrix in which the grains were dispersed reduced the overall transmission of light, and saturated colors could only be achieved by diminishing the brightness of other colors. To make a strong blue, the red and green grains would have to be darkened, so saturated areas appeared as less bright, giving the Autochrome a tonal scale unlike that of any other process.

Part of what makes these early color photographs so fascinating for today’s audience is the unique perspective they offer, a glimpse into a period of humanity’s history we’re accustomed to seeing only in black and white – and that, in turn, we’ve grown used to imagining only in black and white as well. Just as the men and women of the early 20th century would have been amazed to see the world around them in such vivid mechanical reproduction for the first time, we in the 21st century find cause for astonishment too, not now in the colors of the present but the colors of the past.

Sources:

Richard Benson, “The Printed Picture”, published by The Museum of Modern Art, New York 2009.

John Wood, “The Art of the Autochrome. The Birth of Color Photography”, Iowa 1993.

Bertrand Lavédrine, Jean-Paul Gandolfo, “The Lumière Autochrome. History, Technology, and Preservation”, Los Angeles 2013.

André Barret, “Autochromes. 1906/1928”, Paris 1978.

Hanno Platzgummer, “Farben aus der Dunkelkammer. Die Autochrome des Franz Bertolini. 1908-1925”. Innsbruck 1996.

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

Pleasantville (movie trailer) 10 movies by The Lumière Brothers Kodachrome (movie trailer) Documentary: National Geographic - The Last Roll of Kodachrome

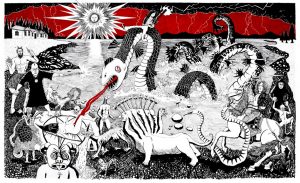

‘Demon’ comes from the Greek δαίμων or δαιμόνιον.

Of Demons, Spirits and Other Creatures

Schon raschelt eine hier und wird sogleich mich hören.

Der Herr der Ratten und der Mäuse,

Der Fliegen, Frösche, Wanzen, Läuse

Befiehlt dir, dich hervor zu wagen

Und diese Schwelle zu benagen,

So wie er sie mit Öl betupft-

Da kommst du schon hervorgehupft!”

To conjure up a lengthier spell,

One’s rustling here that will do well.

The Lord of Rats and Mice,

Of Flies, Frogs, Bugs and Lice,

Summons you to venture here,

And gnaw the threshold where

He stains it with a little oil –

You’ve hopped, already, to your toil!

“[…] Proposuimus et magica theoremata, in quibus duplicem esse magiam significavimus, quarum altera demonum tota opere et auctoritate constat, res medius fidius execranda et portentosa. Altera nihil est aliud, cum bene exploratur, quam naturalis philosophiae absoluta consumatio. Utriusque cum meminerint Greci, illam magiae nullo modo nomine dignantes [goeteian] nuncupant, hanc propria peculiarique appellatione [mageian], quasi perfectam summamque sapientiam vocant. Idem enim, ut ait Porphyrius, Persarum lingua magus sonat quod apud nos divinorum interpres et cultor. […] illa irrita et vana, haec firma fidelis et solida. […] Meminit et Plotinus, ubi naturae ministrum esse et non artificiem magum demonstrat […] Illa denique nec artis nec scientiae sibi potest nomen vendicare; haec altissimis plena misteriis, profundissimam rerum secretissimarum contemplationem, et demum totius naturae cognitionem complectitur. Haec, inter sparsas Dei beneficio et inter seminatas mundo virtutes, quasi de latebris evocans in lucem, non tam facit miranda quam facienti naturae sedula famulatur. Haec universi consensum, quem significantius Graeci [sumpatheian] dicunt, introrsum perscrutatius rimata et mutuam naturarum cognitionem habens perspectatam, nativas adibens unicuique rei et suas illecebras, quae magorum [iunges] nominantur, in mundi recessibus, in naturae gremio, in promptuariis arcanisque Dei latitantia miracula, quasi ipsa sit artifex, promit in publicum, et sicut agricola ulmos vitibus, ita magus terram caelo, idest inferiora superiorum dotibus virtutibusque maritat. […]”

excerpt from: Giovanni Pico della Mirandola,

“Oration on the Dignity of Men”, 1486

Sources:

Bible Server

RDK Labor “Dämonen”

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe “Faust 1”

Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463-94) “Oration on the Dignity of Man (1486)

The Latin Library

All artworks are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, 'Oration on the Dignity of Men', 1486 (full text English) Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, 'Oration on the Dignity of Men', 1486 (full text Latin) Oration on the Dignity of Men - Audiobook Monsters in Art Hieronymus Bosch - The Garden of Earthly Delights Of Monsters and Men - Dirty Paws Kawanable Kyōsai’s Night Parade of One Hundred Demons (1890) The Spider Monster Creating Monsters in the Mansion of Minamoto no Yorimitsu Milena Sidorova - The Spider Dance

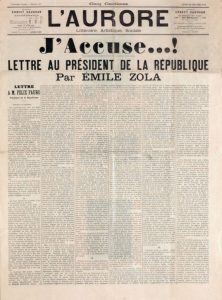

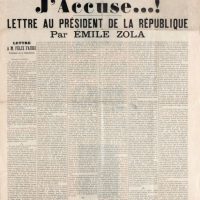

“It remains an indisputable historical law that history will not allow contemporaries to recognize the first stirrings of the great movements which define their era.”

“As for the people I am accusing, I do not know them, I have never seen them, and I bear them neither resentment nor hatred. To me they are mere entities, spirits of social evil. And the act I am accomplishing here is no more than a revolutionary way to hasten the explosion of truth and justice.”

Émile Zola, “Letter to Mr. Félix Faure. President of the Republic” in: L’Aurore, January 13, 1898

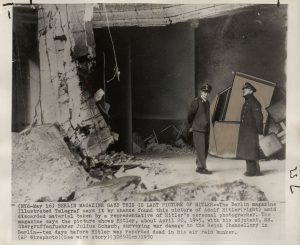

Hitler Starts Drive to Capture Reichstag Majority.

Before a frantically cheering crowd which packed the huge sportspalast in Berlin, Feb. 10, chancellor Adolf Hitler, firing the opening gun in his drive to capture a Reichstag majority in the election March 5, blamed socialist governments for all of Germany’s ills. He is shown here delivering his fiery speech in the Sportspalast.

“The high unemployment, the spiritual Depression following from the economic, the addict’s urge to numb oneself, the activity of unscrupulous parties, all of these were the signs of the coming storm. And neither was the eerie silence before the storm missing – the languor of a heart, crippled as if by epidemic. It drove some to set themselves against the storm and its stillness. They were pushed aside. People would rather listen to the hollering carnival barkers and drummers hawk their panaceas and snake oil. They ran after them, out into the abyss, in which we now, more dead than alive, have arrived.”

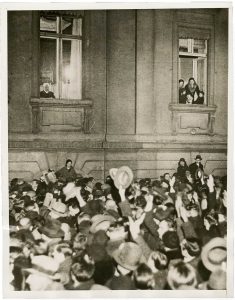

When Hitler Became Chancellor

Standing in the window at upper left, President Paul von Hindenburg silently acknowledges the cheers of thousands who journeyed to the palace to acclaim him after his appointment of Adolf Hitler as chancellor of Germany, in Berlin.

“So they carefully practiced their method: always only one dose at a time, and after that dose a short break. Always only one single pill at a time, and then a moment to wait and see if that hadn’t been too strong, if the world’s conscience could still tolerate the dosage. And as the European conscience – to the detriment and disgrace of our civilization – stressed zealously its indifference, since after all these acts of violence were happening ‘that side of the border,’ the doses grew ever stronger, until finally all of Europe perished from them.”

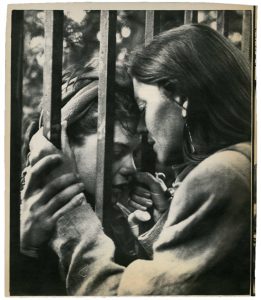

An East German mother cries while saying goodbye to her daughter outside the West German Embassy in Prague, Czechoslovakia. The mother returned to East Germany Saturday, and the daughter stayed with more than 3,000 refugees who left for the West Sunday

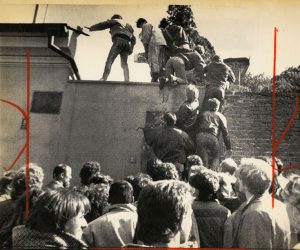

East German citizens, using ladders built from boards, scale the walls of the West German Embassy in Prague, Czechosslovakia, in a desperate attempt to reach the first step in their bid for freedom.

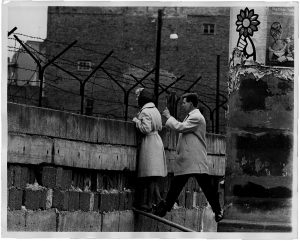

Accompanied by her boy friend, this blonde West Berlin girl stands on a precarious perch near the top of the wall to talk with her mother on the East Berlin side. While it’s just an exciting tourist attraction for many, it’s a heart-breaking “visiting room” for the enormous prison that East Berlin has become for some.

Break in the Barrier East Berlin: An East German border guard stands on duty at the hole in the Berlin dividing wall, which was caused by a truck attempting to break through to freedom in West Berlin. Two men in the truck which rammed the wall had to flee under a hail of bullets after the vehicle was stopped by the wall. Reports said the two men escaped on foot as the East German guards fired on them.

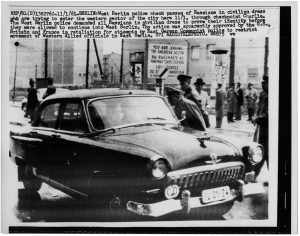

Berlin: West Berlin police check passes of Russians in civilian dress who are trying to enter the western sector of the city here 11/1, through checkpoint Charlie. The West Berlin police demanded all Russians in civilian dress to prove their identity before they were allowed to continue into West Berlin. The action was apparently approved by the U.S., Britain and France in retaliation for attempts by East German Communist police to restrict movement of Western Allied officials in East Berlin.

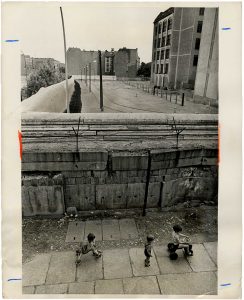

Berlin: Young children play near the Berlin Wall, on the western side. It is a wall that has brought sorrow to many, and freedom to few. Improved security procedures employed by the Communists have cut down the number of attempted and successful escapes. In the background are apartment buildings that are under construction.

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

The US Constitution Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany Constitution française du 4 octobre 1958 Costituzione della Repubblica Italiana (Principi fondamentali) Paper on Conflict and Fragility Fact Sheet EU Conflict Early Warning System

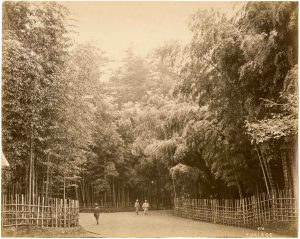

Photography was first introduced to Japan at a time of great upheaval in the country.

Early Photography in Japan

Fundamental political, social, and economic convulsions were followed by rapid reform and modernization. In the midst of it all, early photographers, both western and Japanese, were able to capture the people, places, and events of a changing world on camera.

The story of photography’s spread throughout Japan begins on the southern island of Kyūshū. During the Edo period (1615-1868), Kyūshū’s dominant clans obtained information regarding the outside world from Nagasaki, via the small Dutch trading outpost on the artificial island of Dejima. It was through Dejima that photography was first introduced to Japan. Since literature regarding early photography – and teachers, necessarily foreign, of the new craft – were scarce, early enthusiasts had to rely on personal encounters with foreign professionals to acquire photographic skills and knowledge of their own.

It was around 1846 when the daguerreotype camera, using silver plates, was first brought to Japan. One such apparatus was brought from Dejima to the Takeo clan by a merchant named Ueno Shunnojō, whose son, Hikoma, would go on to become an accomplished photographer in his own right. The Takeo clan returned the daguerreotype to the Dutch, however, unable to understand how to use it. It was only after that that some of Dejima’s own residents, notably doctors like Van den Broek and his successor Pompe, along with their Japanese medical students, attempted to learn the art themselves, aided by little more than Dutch books and manuals. At the same time, the Satsuma and Fukuoka clans also began tackling the secrets of the photographic process. Each clan had achieved partial success with silver plates by the latter half of the 1850s; for this reason, those few years can be seen as the true dawn of photography in Japan.

Today, 75 years later, the photographs taken in Nagasaki on August 10, 1945, are considered the most extensive eyewitness account of the bombing, and the “ground zero” of Atomic Photography.

The encounters between the French photographer P. Rossier and early Japanese pioneers of photography, such as Furukawa Shunpei, Maeda Genzō, and Ueno Hikoma, brought about further developments, in leaps and bounds, in Japanese photography. Rossier came to Nagasaki as a correspondent, and subsequently became the first photographer to sell landscape photographs of Japan in Europe.

When Felice Beato (1834 – c. 1900) established a photographic studio in Yokohama in 1863, he was at the height of his creativity. At this point Beato had already built up an impressive track record as a commercial photographer, having chronicled the Crimean War, the Indian Mutiny and the Second Opium War in China. Beato was therefore unique among his western contemporaries in Japan for his photographic experience. During the remainder of the 1860s, and well into the following decade, Beato enjoyed a reputation as the country’s premier photographer, until he sold his studio to Baron von Stillfried in 1877. Beato’s work remains the first significant body of photographs taken by a western photographer living and working in Japan, one with which both Japanese and westerners were familiar. The history of photography – not only in Japan, but also as a worldwide whole – is richer as a result of his life, his work, and the artistic encounter it engendered.

Hand-Colored Photographs

Throughout the nineteenth century, photography was entirely black and white. While differences in shading might be discernable from one print to another, depending on the exact process used to produce them, the data captured by cameras themselves was monochromatic. This was because silver halides – the family of salts that are light-sensitive enough for use in cameras – only respond to light at the blue end of the visual spectrum, which made recording colors in other parts of the spectrum difficult. There already existed a long history of hand-coloring etchings and engravings, though, and this practice was easily transferred to the new medium of the photograph.

The daguerreotype in its earliest form had a dull, gray appearance, which was often relieved by applying pale red highlights to the subject’s cheeks or spots of gold to the buttons on a jacket.

In Japan, albumen prints (produced for the tourist trade) were often treated with wild applications of color – cherry blossoms became pink, hanging wisteria blue. These modifications were made with diluted oil paints prepared for the purpose. Even long after the invention of color photography these oil colors were still sold in kits, so that the favorite family portrait could be customized and made more lifelike.

Sources:

Terry Bennett, “Photography in Japan. 1853-1912”, Singapore 2006.

Nicole Coolidge Rousmaniere, Mikiko Hirayama, “Reflecting Truth. Japanese Photography in the Nineteenth Century”, Amsterdam 2004.

Richard Benson, “The Printed Picture”, published by the Museum of Modern Art, New York 2008, p. 186.

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

How Colorized Photos Helped Introduce Japan to the World Tourism and Science in Early Japanese Photographs Sites of 'Disconnectedness': The Port City of Yokohama, Souvenir Photography, and its Audience Digital Photo Colorization The Paper Time Machine Cees Nooteboom Explores the Ancient Japanese Temple Kozan-ji Sam Francis in Japan by Richard Speer

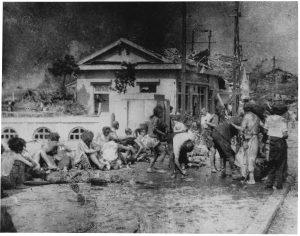

Eyewitnesses of the final bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Yoshito Matsushige

Yoshito Matsushige (1913-2005) was born in Kure, Hiroshima. As a photojournalist, he took five photographs on August 6, 1945, the day of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. At the time of the explosion, Matsushige was at home, 2.7 km south of the hypocentre. He is the only person to have captured an immediate, first-hand photographic account of the bombing. Matsushige dedicated most of the rest of his life to organizing and preserving the photographic history of the atomic bombing of his hometown.

“I had finished breakfast and was getting ready to go to the newspaper when it happened. There was a flash from the indoor wires as if lightening had struck. I didn’t hear any sound, how shall I say, the world around me turned bright white. And I was momentarily blinded as if a magnesium light had lit up in front of my eyes. Immediately after that, the blast came. I was bare from the waist up, and the blast was so intense, it felt like hundreds of needles were stabling me all at once. The blast grew large holes in the walls of the first and second floor. I could barely see the room because of all the dirt. I pulled my camera and the clothes issued by the military headquarters out from under the mound of the debris, and I got dressed. I thought I would go to either the newspaper or to the headquarters. That was about 40 minutes after the blast. Near the Miyuki Bridge, there was a police box. Most of the victims who had gathered there were junior high school girls from the Hiroshima Girls Business School and the Hiroshima Junior High School No.1. They had been mobilized to evacuate buildings and were outside when the bomb fell. Having been directly exposed to the heat rays, they were covered with blisters, the size of balls, on their backs, their faces, their shoulders and their arms. The blisters were starting to burst open and their skin hung down like rugs. Some of the children even have burns on the soles of their feet. They’d lost their shoes and run barefoot through the burning fire. When I saw this, I thought I would take a picture and I picked up my camera. But I couldn’t push the shutter because the sight was so pathetic. Even though I too was a victim of the same bomb, I only had minor injuries from glass fragments, whereas these people were dying. It was such a cruel sight that I couldn’t bring myself to press the shutter. Perhaps I hesitated there for about 20 minutes, but I finally summoned up the courage to take one picture. Then, I moved 4 or 5 meters forward to take the second picture. Even today, I clearly remember how the view finder was clouded over with my tears. I felt that everyone was looking at me and thinking angrily, “He’s taking our picture and will bring us no help at all.” Still, I had to press the shutter, so I harden my heart and finally I took the second shot. Those people must have thought me duly cold-hearted. Then, I saw a burnt streetcar which had just turned the corner at Kamiya-cho. There were passengers still in the car. I put my foot onto the steps of the car and I looked inside. There were perhaps 15 or 16 people in front of the car. They laid dead one on top of another. Kamiya-cho was very close to the hypocenter, about 200 meters away. The passengers had stripped them of all their clothes. They say that when you are terrified, you tremble and your hair stands on end. And I felt just this tremble when I saw this scene. I stepped down to take a picture and I put my hand on my camera. But I felt so sorry for these dead and naked people whose photo would be left to posterity that I couldn’t take the shot. Also, in those days we weren’t allowed to publish the photographs of corpses in the newspapers. After that, I walked around, I walked through the section of town which had been hit hardest. I walked for close to three hours. But I couldn’t take even one picture of that central area. There were other cameramen in the army shipping group and also at the newspaper as well. But the fact that not a single one of them was able to take pictures seems to indicate just how brutal the bombing actually was. I don’t pride myself on it, but it’s a small consolation that I was able to take at least five pictures. During the war, air-raids took place practically every night. And after the war began, there were many foods shortages. Those of us who experienced all these hardships, we hope that such suffering will never be experienced again by our children and our grandchildren. Not only our children and grandchildren, but all future generations should not have to go through this tragedy. That is why I want young people to listen to our testimonies and to choose the right path, the path which leads to peace.”

Yosuke Yamahata

At the time of the final bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, in August 1945, Yōsuke Yamahata (1917-1966) was a propaganda photographer for the Japanese News and Navy Divisions of the Information Bureau. Yamahata spent most of the 1940s in Southeast Asia, where he photographed the deployment of the Japanese military. When the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima he was 28, and just transferred back to Tokyo. He had driven through Hiroshima the previous day, on his way to the military base In Hakata. Three days later Nagasaki was bombed. An investigative team left Hakata for Nagasaki, or what remained of it, that same evening. It consisted of Yamahata, the writer Jun Higashi, the painter Eiji Yamada, and two military escorts. It was night the next day when they returned, and when Yamahata, gone immediately to develop his film alone in his darkroom, made the decision to keep it, not to turn it over to the News and Information Bureau. It wasn’t until the end of the month – after Japan had surrendered, and with encouragement from his father – that Yamahata published the first of his pictures, in daily newspapers distributed nationwide. Soon afterwards the new press censorship orders from General MacArthur, now Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, took effect, and banned any publication in connection with nuclear warfare for the next seven years. It was 1952 before censorship was lifted again and Yamahata’s photographs were made available to the public, in a monograph entitled Atomized Nagasaki. For the photographer, the following years were characterized by the push and pull of his pictures’ use, or misuse, as military propaganda, and their place in the struggle for nuclear disarmament and world peace.

Today, 75 years later, the photographs taken in Nagasaki on August 10, 1945, are considered the most extensive eyewitness account of the bombing, and the “ground zero” of Atomic Photography.

Publication “X-Ray Japan -1945” Get Your Copy Here

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

Yoshito Matsushige's video testimony by Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum Documentary 'Tale of Two Cities' Document by U.S. Army Signal Corpse Pictorial Division 'The Atom Strikes!'

“How full of the creative genius is the air in which these are generated!

I should hardly admire more if real stars fell and lodged on my coat.”

Henry David Thoreau

Snow Studies

Snowflakes are fascinating objects, only revealing their full beauty underneath a microscope. Wilson Alwyn Bentley (1865-1931), from Vermont, first became fascinated by these tiny crystals as a child, spending cold winter days marveling at the secrets they revealed beneath his parents’ microscope. But snow melts all too quickly, and those crystals soon were nothing more than drops of water. Bentley’s urge to capture that fleeting instant of frozen beauty transformed him into one of pioneers of snow photography. He succeeded in attaching a microscope to his camera in 1885, and soon thereafter was able to create the earliest confirmed photograph of a snowflake. Some researchers, though, ascribe that honor instead to the German natural scientist Johann Heinrich Flögel (1834-1918), who, it is claimed, took the first snow crystal photograph in 1879.

How To ?

Bentley knew that he needed a dark background for his work, in order to see the snowflakes as clearly as possible, and that he had to get his subjects beneath the lens as quickly as possible. What presented itself to him as the optimal solution was to cover a tray in black velvet and ferry the snowflakes directly to the camera on that. Sitting outside with the tray, he would watch the black surface through a magnifying glass until a perfectly symmetrical crystal appeared upon the velvet. He used a sliver of wood to move the snowflake onto a slide and brought that into the shed where he’d set up the microscope camera. He brought the microscopic image into focus using a string contraption he’d designed for use by gloved hands. A final challenge was posed by air itself; every careless breath could melt the crystal. Everything had to be accomplished with the greatest speed. Once preparations were all in place, he could expose the glass slide and the crystal upon it; the exposure time could last anywhere from between eight to a hundred seconds.

Earliest Depictions of Winter Landscapes in Art

An illustrated copy of the Tacuinum Sanitatis – an originally Arab text revolving around matters of health and well-being – happened to be owned by the same Bishop of Trento who, early in the fifteenth century, commissioned Master Wenceslas of Bohemia to execute a series of frescoes for the episcopal palace’s so-called Eagle Tower. The subject was the cycle of months, and although that theme could already be found in books and illustrated manuscripts, the Eagle Tower frescoes have been described as the first monumental depiction of the year in its calendar divisions. The fresco for the month of January, depicting a snowball fight, is also possibly the first large-scale painting showing a true winter scene.

Around the same time as the Trento frescoes, the Limbourg Brothers began to work on the Très Riches Heures, a book of hours commissioned by the Duc de Berry. The month of February in the lavishly illustrated calendar features a small farm in a frozen, snowy landscape, under a grey sky. Whereas the snow of Trento’s fresco vaguely resembles dirty cotton or wool strewn about the ground, the snow in the Limbourg’s February looks like it has fallen from the sky. Moreover, the snow is integrated into the actual composition of the work.

Sources:

Philip McCouat, “The Emergence of the Winter Landscape. Bruegel and his predecessors”, in: Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com, 2013/2014.

Kenneth G. Libbrecht, “The Formation of Snow Crystals. Subtle Molecualr Processes Govern the Growth of a Remarkable Variety of Elaborate Ice Structures”, in: American Scientist, Vol. 95, 2007, www.americanscientist.org

Kurt Tutschek, “Der Mann, der als Erster eine Schneeflocke fotografierte”, in: Der Standard, 2018, www.derstandard.de

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

How To: proper snow photography Nanook of the North (1922) The Formation of Snow Crystals Smilla's Sense of Snow Frances Chickering's Snow Flake Album (1864) How To Recognize a Fake Part I How To Recognize a Fake Part II

A “found object” is understood to be an object, part of the everyday or natural surroundings,

which is made into a work of art.

Message in a Bottle

The inhabitants of the Westman Islands, off the south coast of Iceland, would use the ‘Flaschenpost’ when they wanted to send letters to friends on the south coast of Iceland itself. Along with the correctly addressed letter, they would put a little tobacco in the bottle, as a kind of tip for whoever found the bottle and forwarded its written contents to their final destination. The bottles would be thrown into the sea when the south wind was blowing, when they would be carried with certainty over to Iceland.

According to legend, Christopher Columbus sent a ‘message in a bottle’ way back in 1493, during his journey to the west; in the midst of a raging storm, he committed a cedar barrel full of messages for Ferdinand II and his wife Isabella I to the waves. Presumably, that bit of mail never reached its intended recipients.

The Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers (1924-1976), who held Edgar Allan Poe in the highest esteem, created this illustrating object-installation in 1974. “Le Manuscrit trouvé dans une Bouteille” is composed of a Bordeaux wine bottle, upon which the words “The Manuscript 1833” have been printed. Broodthaers is referring here to Poe’s 1833 short story “MS. Found in a Bottle,” which won Poe first prize in a writing competition for the Baltimore Saturday Visiter. In it, Poe describes an ocean journey that set off from Batavia, on the island of Java, towards the Sunda Archipelago. The freight-laden ship gets caught in a storm that destroys its masts and rigging, and drifts now, a wreck with only two survivors, into the southern polar night. There, they collide with an enormous ship, which strikes them with such force that the narrator is tossed over and onto it. He hides himself from the crew, in the belly of the ship, but eventually realizes the sailors don’t see him, and that he can move among them unnoticed. He finds some writing materials for himself, in order to compose the manuscript that he plans to send forth as a message in a bottle. His writing comes to a close as the ship hurtles towards an abyss and shoots down into it: “The circles rapidly grow small – we are plunging madly within the grasp of the whirlpool – and amid a-roaring, and bellowing, and thundering of ocean and of tempest, the ship – is quivering, oh God! and – going down.”

Objet trouvé

A “found object” is understood to be an object, part of the everyday or natural surroundings, which is made into a work of art. Often the item in question will be disassembled or painted, and ‘alienated’ from itself or made unfamiliar to the viewer. The found object has its origins in the artistic circles of Dadaism, as a three-dimensional extension of the collage, to create new interrelations of meaning. Displaced from its original function and context – but still recognizable – it creates a connection between artwork in a museum setting and non-artistic reality.

Andy Warhol (1928-1987) dedicated himself to Coca-Cola bottles for many years in a row during the 1960s. The inspiration spawned a series of graphite drawings and large-format paintings, including one of his trademark serial creations featuring over 100 cola bottles. This is a bottle recognizable worldwide, thanks to its patented form (and content!). Robert Rauschenberg had incorporated three Coca-Cola bottles into his Combine-objects as early as 1958. In this same tradition, Andy Warhol created an object installation, which takes up an everyday found object and places it into the centre of the work of art, furnishing it with colour and creating thereby a singular whole which is simultaneously painting and installation: a still life, both the subject of the installation and the object itself.

Still Lifes

Pliny reports that in the competition between the artists Zeuxis and Parrhasios, Zeuxis painted an ensemble of grapes so deceptively real that the birds flew down to peck at it. Assured of his victory, he went to draw back the curtain hiding Parrhasios‘ painting. To Zeuxis‘ embarassement, though, the painting was the curtain itself!

Sources:

Edgar Allan Poe, “Der Mord in der Rue Morgue und andere Erzählungen”, Buch und Zeit Verlagsgesellschaft, Köln o.J., S. 80.

“Handwörterbuch des Postwesens”, 1. Auflage, S. 236.

David Bourdon, “Andy Warhol”, New York 1989.

John Wilmerding, “The Pop Object. The Still Life Tradition in Pop Art”, New York 2013.

Willy Rotzler, “Objektkunst von Duchamp bis zur Gegenwart”, Köln 1972.

Find all exhibited images here

Other Diversions

Message in a Bottle Exhibit The Police - Message in a Bottle

+49 89 29 73 42

+49 89 29 73 42