Month: June 2021

The portrayal of the human figure is one of the oldest themes and subjects in the entire history of artistic expression.

Me, Myself and I

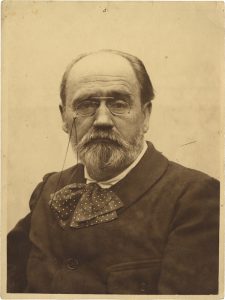

The portrayal of the human figure is one of the oldest themes and subjects in the entire history of artistic expression. As it became a more distinct genre, the portrait as such took over many of the roles and functions of those early human images, such as a certain immortalization of the subject after death, representative duties and deputized purposes in lieu of the subject himself. Portraiture experienced its heyday from the late Middle Ages through to the 17th century. This was in stark contrast to the era of early Christianity, which, on account of the young religion’s adamant rejection of potentially idolatrous representative art, knew very little in the way of individual likenesses and portraits.

The history of the portrait begins at the moment when the ambition of artist turns towards making resemblance the main subject of their artwork. Resemblance had been understood since the late 15th century to be not only a matter of external appearance, but also one of inner essence and being. While portraits of the late Middle Ages were overwhelmingly formulaic, a new development in painting began to take hold after 1300, according to which the identifiable features and physical characteristics of one particular human subject were mixed with images and allusions from the overall canon of sacred, mythological, and historical subjects and themes. The lords and patrons were the first faces recognizable in the painting, but their presence still had to be legitimized by the portrayal of an accompanying saint.

It was only much later, with the beginning of the Renaissance and the era’s new understanding of Man as an autonomous individual, that the portrait came to conquer the private sphere and an emerging middle class. Toward the end of the Quattrocento the psychological ‘moment’ came into view, which naturally cannot be understood in the modern sense. The essence of a person, his mental state and emotional psychology, wasn’t achieved through any sort of analytical carving away, but was betrayed instead through subtle means. The fact that a portrait always, by definition, transcends the status of an exact one-to-one snapshot, but is rather always an aesthetic construct, is due to the desire of those portrayed to tell the world something about themselves. Merits, virtues, values, education, status and position in society are thereby hidden, in and by means of symbols and symbolisms – in attributes, interiors, landscapes, clothing, and posture.

It was at this same historical moment that self-portraiture began its ascendance to the prominent position it occupies today in the portrait-painting tradition. It served, on the one hand, a personal purpose for the artist himself, a place for private experimenting, and on the other hand can be understood in a broader social sense as one expression of burgeoning self-confidence in the individual. After all, as the role of painter as artist came to be held in greater and greater esteem over the course of the Renaissance, so rose as well the worth of his own image – an image at first half-hidden in larger compositions, gradually growing to be a stand-alone portrait in its own right.

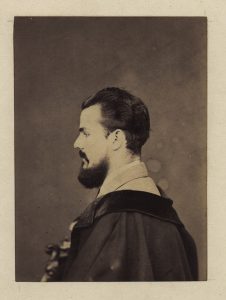

In the 16th and 17th centuries, portraiture reached its zenith. The portrait has now finally arrived in the both the civic and private realm. Much was to change from the 19th century onwards: with the advent of photography, a quick and convenient technology came onto the market, one which created an image where reality and recreation were nearly identical.

The painters of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, in turn, shook the mainstream artistic world by finally and forcefully separating color and shape from one another. Painting triumphed over visually perceived reality. With advances in photography, new demands were placed on portrait painting, ones which inevitably drew further and further away from the artistic and practical demands being met by technology-based forms of visual reproduction.

Mummy Portraits

The earliest movable portraits have their origins at about the time of Christ’s birth, from the Faiyum, a lowland oasis region lying some three hundred kilometers south of Alexandria. Egypt had only recently been annexed by the Romans, a change in jurisdictional fortune that relegated it to the outskirts of an empire based across the Mediterranean Sea. Roman mercenaries, given leave to become farmers, were settled in the distant province, becoming in the process the foundation of a new, hybrid culture in the Faiyum.

The ancient belief that the deities humans worshiped were bound to one particular place belonged just as much to the Egyptians as it did to the Romans. The mercenaries settled in the Faiyum, therefore, had Egyptian gods to worship. The gods of the Egyptian countryside were, for them, simply different manifestations of the true gods; the Egyptian Amon and the Hellenic Zeus were one and the same person, just as Osiris, Bacchus and Dionysus were. Through the cult of Osiris, however, the Egyptian belief in an afterlife, and its associated burial practices, found its way into the Roman colonies. One such practice was the ancient Egyptian custom of giving human form to the coffins of mummies, or attaching a mask, in the form of an idealized human face, to the coffin’s head, a custom which the Romans of Egypt adopted and modified.

A longstanding practice common among the upper classes of the Roman Empire’s more central provinces was the creation of individualized sculptural portrait busts, for exhibition in a household’s atrium or central courtyard. Just how much of a role that tradition played in the evolution of Faiyum portraiture can be debated; certain similarities, though, seem too striking to ignore. The mummy portraits of Roman Faiyum were painted in encaustic or tempera, on canvas or wood, unlike the earlier Egyptian practice of painting directly onto the sarcophagus, or even the bandages of the mummy itself; moreover, these were individualized portrayals of the deceased, not the standardized representation of a canonical set of human forms as indigenous mummy painting had been. This made them eligible as objects of display, an echo of the portrait busts of ‘home.’ A mummy portrait would be made during its subject’s lifetime, ‘living’ with him in his house until, after the subject’s death, it was wrapped in the mummy’s outermost bandages, at the head, something like a face, peering out from between the strips of linen.

There have been numerous mummy portraits found of children, appearing in their likeness very much alive; considering how unlikely it is that these would have been made during the lifetimes of their young subjects, we can assume that it was acceptable to create these portraits even when the sitter could no longer hold his own pose, at the very least in the case of an early or unexpected death. While that may seem a tad macabre, the practice is nearer to us than we might imagine; the modern age has passed down daguerreotypes and even photographs to us of children and babies who have already died, propped up before the lens to appear as among the living one last time.

source: G. Möller. “Das Mumienporträt,” Wasmuths Kunsthefte, Band I, Berlin o.J.

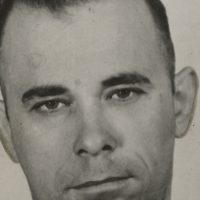

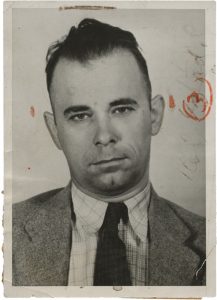

Mugshots

The word ‘mugshot’ is an informal term used describe an official photo taken of suspects in the course of police investigations. The photos serve as a tool to aid in identifying the perpetrator and can be used in the course of ongoing manhunts or criminal trials. In the USA, mugshots enter the public domain immediately, available to everyone through the Freedom of Information Act. The police usually take two mugshots at the time of arrest: one frontal, and one in profile. It is no longer common for the subject to hold a blackboard with his personal information on it, due to advances in digital photography and data recording.

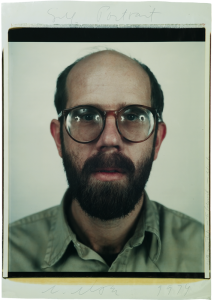

Selfies

When someone takes a selfie, they are turning themselves into art. This is not quite the same thing as simply making a picture of oneself – that is, of making a self-portrait. To take a selfie means to take a picture of yourself in which and for which you are already transformed into art. A selfie is, then, in actual fact an image of an image.

The most pointed criticism of selfies distinguishes these from other categories of image, and from self-portraiture in particular. Indeed, although we might identify certain painters throughout history whose choice of themselves as primary subject aroused suspicion, the creation of self-portraits as such was never wholescale condemned as a vice, nor did any meaningful (and critical) discourse around the topic exist. An explanation might be found in the small number of artists who painted self-portraits in the first place; for reasons of sheer quantity (or lack thereof), self-portraiture as a genre or practice could not be fraught with many societal consequences. Perhaps, though, the particular circumstance of the selfie, the essence of its creation, plays a role as well – namely, that whereas a self-portrait is only an image one creates with himself as subject, the selfie must go further, is an image taken of a person already in the act of making himself into an image, into art, to be reproduced in the final image we call ‘selfie.’

Sources:

Wolfgang Ullrich, “Selfies. Die Rückkehr des öffentlichen Lebens”, Verlag Klaus Wagenbach, Berlin, 2019.

G. Möller. “Das Mumienporträt,” Wasmuths Kunsthefte, Band I, Berlin o.J.

Dorothee Fauth, “Kunstlexikon. Porträt,” June 2, 2005, for Hatje Cantz online:

Kunstlexikon Portrait

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

Mummy Portraits Podcast Mummy Portraits 24 Very Early Selfies How Artists Explore Identity by MoMA Selfportraits by Arnold Schoenberg Selfportraits by Schirn Kunsthalle Virtual Tour Egyptian Museum Munich Hieroglyph course (in German) The Art of the Selfie Self Portrait van Gogh

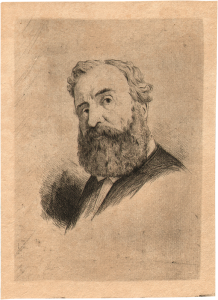

(from a photograph of a Daguerrotype by an unidentified artist), 7,1 x 8,8 cm, © Daniel Blau, Munich

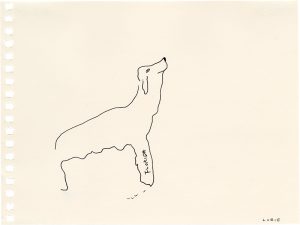

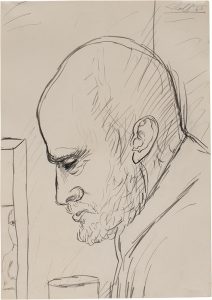

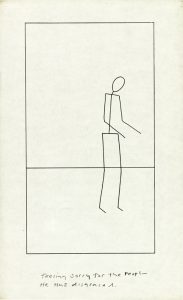

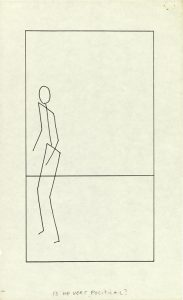

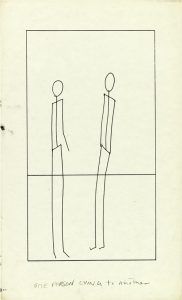

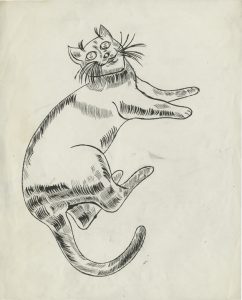

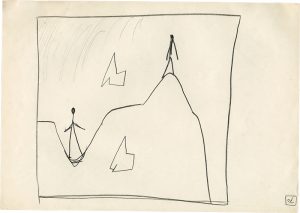

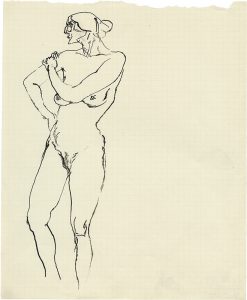

In the history of art, the simple line drawn has always held a position of fundamental importance.

The Fine Line

The Fine Line

In the history of art, the simple line drawn has always held a position of fundamental importance. The earliest ‘artworks’ still available to us today are prehistoric engravings in caves, which, using only the simplest means – in only a few lines – clearly show man and animal, weapon and tool, distinguishable even today by their distinctive and characteristic contours. A high-water mark in the importance of line-based drawing – il disegno – can be found in the theoretical debates that raged through the world of Italian art in the years after the Florentine Academy was founded, debates whose central theme was the matter of whether il disegno played a more essential role in artistic creation than the shading and tonality embodied by the concept of Venetian colorito. The Paragone, the debate of the academies between contour and color, carried on through the centuries until it reached another zenith with the Poussinists and Rubenists. (1)

According to art historians and critics of the 20th century, ‘the stroke’ – or ‘the line’ – incorporates the entirety of an artist’s personal drawing style, both its conscious and unconscious characteristics. (2) The line sketches the contours of a shape only in certain regards – “the essentials are marked out, and everything else falls away.” (3) This conception of the line harks back to Leonardo da Vinci, himself of the convinced opinion that no true ‘Line’ in artistic terms exists in nature (4), and that what we conceive of as such is instead the abstraction of those shapes that are at hand and visible around us. “Lines confine and connect, characterize and accentuate.” (5) The line is a symbol, an attempt to make reality visible and comprehensible, but not an immediate, unadulterated imitation itself.

Delacroix, for example, in a letter dated the 15th of July, 1849, presents his own perspective on the matter. He positions himself in opposition to the idea that line and beauty have some sort of fundamental linkage, an idea that had enjoyed widespread currency among artists since the 18th century. “That often-discussed Beauty, which one fellow might see in a serpentine line, and another in a straight one – they’re both insisting on seeing nothing but lines. I stand at my window and behold a miraculous landscape, but the thought of a line never once crosses my mind. A lark sings, the river sparkles as though it’s made of a thousand diamonds, the leaves whisper; where are the lines, that can reflect such delightful impressions?” (6)

The art historian and author Julius Meier-Graefe (1867-1935) accused his art-creating contemporaries of “babbling on about the line the same way Xenephon’s Greeks once did about the sea,” (7) although he himself had played a large part in popularizing the line-focused aesthetic. (8) Around 1900, enthusiasm for the line increased again, and in all expressions of aesthetic production, in literature and architecture just as much as in the visual arts. It was now understood primarily as a moving element, and artists experimented with it accordingly. Kandinsky’s 1926 Bauhaus textbook “Point and Line to Plane” created a theoretical approach to the expression of different types of line, from a phenomenological perspective. He differentiates between degree of curvature, line variation, and their alignment on the plane. (9)

Moreover, it is impossible for a line to exist as nothing more than the outline of a shape alone. The variations between thick and thin, subtle and bold, intersecting and parallel, segmented and sweeping, confidently and haltingly drawn, all serve to impart to audience a feeling, a sensation, that goes far beyond the realm of the purely visible. The artist has other tools and techniques at his or her disposal, such as hatching, that can serve to make those sensations, and the visual cues invoking those sensations, even stronger; the result may very well be more along the lines of a sketched abstraction, or a symbol only indicating or standing in for a natural form, rather than something recognizable as a direct and intentional representation of objective reality. By overcrowding and overlapping lines over line, hatching, for instance, is able to convey a sense of plasticity and drama to the viewer, even though, strictly speaking, it remains only a distant reproduction of the shading that occurs in reality. (10)

sources:

(1) Matteo Burioni, Sabine Feser (ed.), “Giorgio Vasari. Kunsttheorie und Kunstgeschichte. Eine Einführung in die Lebensbeschreibungen berühmter Künstler anhand der Proemien”, Berlin 2004, p. 193-196, 229-231

(2) Uwe Westfehling, “Meisterzeichnungen von Leonardo bis zu Rodin”, Cologne 1986, p. 16

(3) Westfehling, p. 16

(4) Walter Koschatzky, “Die Kunst der Zeichnung, Technik, Geschichte, Meisterwerke, Munich 1981, p. 29

(5) Westfehling, p. 17

(6) Kurt Badt, “Eugène Delacroix. Zeichnungen. Eine Einführung auf Grund der Tagebücher des Künstlers”, in: “Eugène Delacroix. Werke und Ideale. Drei Abhandlungen”, Cologne 1965, p. 32

(7) Julius Meier-Graefe, “Entwicklungsgeschichte der Modernen Kunst. Vergleichende Betrachtungen der bildenden Künste, als Beitrag zu einer neuen Ästhetik”, Stuttgart 1904 (new edition by Hans Belting), Munich 1987, Bd. 2, p. 681

(8) Sabine Mainberger, “Experiment Linie. Künste und ihre Wissenschaften um 1900”, Berlin 2010, p. 7-8

(9) Raphael Rosenberg, “Die Linie in der ästhetischen Theorie des 18. und 19. Jahrhunderts”, in: Erich Franz (ed.), “Freiheit der Linie. Von Obrist und dem Jugendstil zu Marc, Klee und Kirchner”, Münster 2007, p. 12, after Beate Kemfert (ed.), “Linie und Skulptur im Dialog. Rodin, Giacometti, Modgliani. Werke aus der Sammlung Kasser/Mochary Family Foundation USA”, Munich 2011

(10) Westfehling, p. 17

All artworks are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

Johnny Cash, ' I walk the line', 1958 Petroglyphs within the Archaeological Landscape of Tamgaly Neanderthal artists made oldest-known cave paintings 45,000-Year-Old Pig Painting in Indonesia May Be Oldest Known Animal Art The Paper Side of Art Flatland - A romance of many dimensions Punkt, Punkt, Komma, Strich-- (Zeichenstunden für Kinder)

+49 89 29 73 42

+49 89 29 73 42