BULLETIN

“It is not the camera but the skill of the operator that produces a realistic-looking photograph”

Retouching in Photography

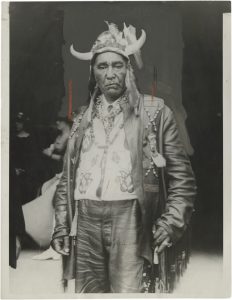

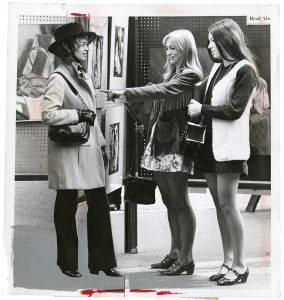

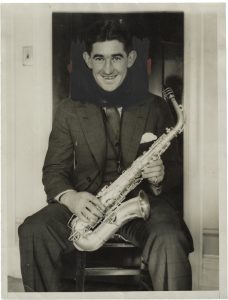

Photographs have been retouched ever since the early days of photography in the 19th century. Over the years, analogue photographers have deployed many darkroom and desk-based techniques as a means of enhancing and manipulating their images. Manual retouching practices include dodging and burning, scratching, airbrushing and marking negatives and prints.

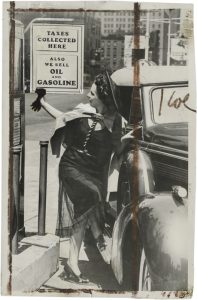

These tangible processes are often visible on vintage press prints, where the skilful hands of photographers and specialist retouchers made notes, painted crop marks and highlighted areas to be reproduced, edited or omitted from the final published images.These highly detailed traces of the creative process are an integral part of analogue photographic history, and are the precursors of many of the digital retouching techniques in common use today.This article presents a short and inevitably incomplete overview of techniques commonly used to modify a photograph during the postproduction process.

Photography has always presented challenges, requiring knowledge of chemical processes, ideal lighting and staging conditions, and the presentation of the final photo in a suitable environment.Essays from the early days of photography in the mid 19th century focus on the question of whether a photograph can ever claim to be a true likeness of reality. The material limitations of lenses and plates often lead to areas of greater darkness or brightness in the image.{1}

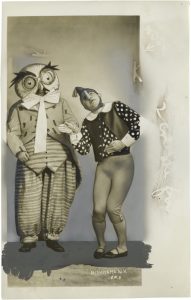

Additionally, the framing of the photograph is contingent on the photographer’s intention and decision-making. The image is by its very nature selective.If a photo needed modifications in the mid 19th century it called for manual interventions such as applying powdered pigment, oil paint, watercolour, crayon or pastel. These retouched prints could even easily be mistaken for paintings.{2} This is understandable given the photographers’ backgrounds – French and British photographers around 1850 “were initially trained as painters, draftsmen, or lithographers”.{3}

Photographers such as Louis Daguerre had a scientific background and applied this to discovering new methods of printing and of modifying the plate or the negative directly to get a pleasant result.{4} Early modifications were generally done either to please the portrayed sitter or to compensate for the lack of colour in early black and white photography.{5}

The introduction in the early 1870s of gelatin dry-plate negatives, which could be extensively reworked with soft lead pencils, led to a dramatic increase in the the demand for skilled studio retouchers. {6}Retouching skills continued to be highly valued by both amateurs and professionals in the 20th century.

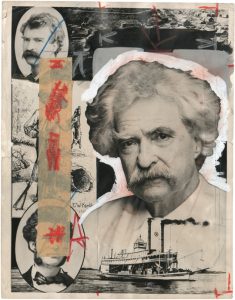

Photomontage techniques involve making a composite photograph by cutting, gluing and collaging two or more photographs into a new image. Sometimes this new image is photographed to produce a final image.

Photomontage has sometimes been applied as a means of creating false images. Such manipulated photographs can be used politically : “The temptation to ‘rectify’ photographic documents has proved irresistible to modern demagogues of all stripes, from Adolf Hitler to Mao Zedong to Joseph McCarthy.”{7}

In the 1950s and 1960s NY crime photographer Weegee refined some of his pictures to caricatures, apart from some advantageous retouches every now and then on his pictures sent to ACME.{8}

The next big step in the history of photography has been achieved by the advent of digital technologies. Now the previously manual processes of retouching are often done on a screen, using a tool named Photoshop.

[1] In an article titled “Photography and Authority”, published in 1864 in the inaugural volume of the Philadelphia Photographer, the Reverend H.J. Morton attributed to the medium a kind of clear-sighted, divine omniscience. The camera, he maintained, “sees everything, and it represents just what it sees. It has an eye that cannot be deceived, and a fidelity that cannot be corrupted“ (in Fineman, footnote 20, H.J. Morton “Photography as an Authority” in: The Philadelphia Photographer 1, no 12, Dec1864, p. 180 [2] Mia Fineman, Faking it. Manipulated Photography before Photoshop, 2012 Metropolitain Museum NY, p. 9 [3] Fineman, p. 45 [4] The optimal solution was to print a landscape from two negatives, one exposed for the land, the other for the sky.(..) At a time when the camera exposures often lasted for several seconds, viewers were amazed by Le Gray’s ability to freeze the motion of breaking waves, and the perfectly backlit clouds drifting above reinforced the feeling of instantaneity. That the clouds and the waves were printed from two separate negatives remained the artist’s secret during lifetime. Fineman, p. 47f. [5] The desire for greater optical realism has by no means been the only motivation for manipulating photographic images. Fineman, p. 15 [6] Fineman, p. 63 [7] Fineman, p. 91 [8] Eg “Draft Johnson for President”, c. 1968

All artwork is available for purchase.

We cannot guarantee the items will still be available upon request.

For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

Other Diversions

Robert Flaherty - Nanook of the North (1922) Staatsoper TV: Oper und Ballett im kostenlosen Live-Stream Royal Opera House The Metropolitan Opera - Nightly Opera Streams Kosmos Heartfield Musee Unterlinden Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz British Museum - African Rock Art Courthard Institute of Art Robert Flaherty - Moana 1926 F.W. Murnau - Tabu: A story of the South Sea, 1931

+49 89 29 73 42

+49 89 29 73 42