BULLETIN

Photography was first introduced to Japan at a time of great upheaval in the country.

Early Photography in Japan

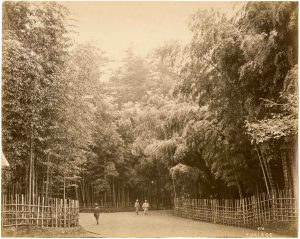

Fundamental political, social, and economic convulsions were followed by rapid reform and modernization. In the midst of it all, early photographers, both western and Japanese, were able to capture the people, places, and events of a changing world on camera.

The story of photography’s spread throughout Japan begins on the southern island of Kyūshū. During the Edo period (1615-1868), Kyūshū’s dominant clans obtained information regarding the outside world from Nagasaki, via the small Dutch trading outpost on the artificial island of Dejima. It was through Dejima that photography was first introduced to Japan. Since literature regarding early photography – and teachers, necessarily foreign, of the new craft – were scarce, early enthusiasts had to rely on personal encounters with foreign professionals to acquire photographic skills and knowledge of their own.

It was around 1846 when the daguerreotype camera, using silver plates, was first brought to Japan. One such apparatus was brought from Dejima to the Takeo clan by a merchant named Ueno Shunnojō, whose son, Hikoma, would go on to become an accomplished photographer in his own right. The Takeo clan returned the daguerreotype to the Dutch, however, unable to understand how to use it. It was only after that that some of Dejima’s own residents, notably doctors like Van den Broek and his successor Pompe, along with their Japanese medical students, attempted to learn the art themselves, aided by little more than Dutch books and manuals. At the same time, the Satsuma and Fukuoka clans also began tackling the secrets of the photographic process. Each clan had achieved partial success with silver plates by the latter half of the 1850s; for this reason, those few years can be seen as the true dawn of photography in Japan.

Today, 75 years later, the photographs taken in Nagasaki on August 10, 1945, are considered the most extensive eyewitness account of the bombing, and the “ground zero” of Atomic Photography.

The encounters between the French photographer P. Rossier and early Japanese pioneers of photography, such as Furukawa Shunpei, Maeda Genzō, and Ueno Hikoma, brought about further developments, in leaps and bounds, in Japanese photography. Rossier came to Nagasaki as a correspondent, and subsequently became the first photographer to sell landscape photographs of Japan in Europe.

When Felice Beato (1834 – c. 1900) established a photographic studio in Yokohama in 1863, he was at the height of his creativity. At this point Beato had already built up an impressive track record as a commercial photographer, having chronicled the Crimean War, the Indian Mutiny and the Second Opium War in China. Beato was therefore unique among his western contemporaries in Japan for his photographic experience. During the remainder of the 1860s, and well into the following decade, Beato enjoyed a reputation as the country’s premier photographer, until he sold his studio to Baron von Stillfried in 1877. Beato’s work remains the first significant body of photographs taken by a western photographer living and working in Japan, one with which both Japanese and westerners were familiar. The history of photography – not only in Japan, but also as a worldwide whole – is richer as a result of his life, his work, and the artistic encounter it engendered.

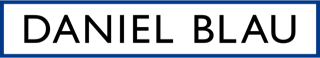

Hand-Colored Photographs

Throughout the nineteenth century, photography was entirely black and white. While differences in shading might be discernable from one print to another, depending on the exact process used to produce them, the data captured by cameras themselves was monochromatic. This was because silver halides – the family of salts that are light-sensitive enough for use in cameras – only respond to light at the blue end of the visual spectrum, which made recording colors in other parts of the spectrum difficult. There already existed a long history of hand-coloring etchings and engravings, though, and this practice was easily transferred to the new medium of the photograph.

The daguerreotype in its earliest form had a dull, gray appearance, which was often relieved by applying pale red highlights to the subject’s cheeks or spots of gold to the buttons on a jacket.

In Japan, albumen prints (produced for the tourist trade) were often treated with wild applications of color – cherry blossoms became pink, hanging wisteria blue. These modifications were made with diluted oil paints prepared for the purpose. Even long after the invention of color photography these oil colors were still sold in kits, so that the favorite family portrait could be customized and made more lifelike.

Sources:

Terry Bennett, “Photography in Japan. 1853-1912”, Singapore 2006.

Nicole Coolidge Rousmaniere, Mikiko Hirayama, “Reflecting Truth. Japanese Photography in the Nineteenth Century”, Amsterdam 2004.

Richard Benson, “The Printed Picture”, published by the Museum of Modern Art, New York 2008, p. 186.

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

How Colorized Photos Helped Introduce Japan to the World Tourism and Science in Early Japanese Photographs Sites of 'Disconnectedness': The Port City of Yokohama, Souvenir Photography, and its Audience Digital Photo Colorization The Paper Time Machine Cees Nooteboom Explores the Ancient Japanese Temple Kozan-ji Sam Francis in Japan by Richard Speer

+49 89 29 73 42

+49 89 29 73 42