BULLETIN

“How full of the creative genius is the air in which these are generated!

I should hardly admire more if real stars fell and lodged on my coat.”

Henry David Thoreau

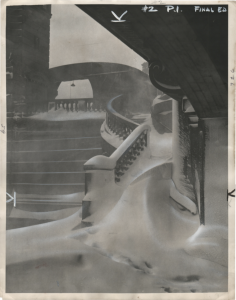

Snow Studies

Snowflakes are fascinating objects, only revealing their full beauty underneath a microscope. Wilson Alwyn Bentley (1865-1931), from Vermont, first became fascinated by these tiny crystals as a child, spending cold winter days marveling at the secrets they revealed beneath his parents’ microscope. But snow melts all too quickly, and those crystals soon were nothing more than drops of water. Bentley’s urge to capture that fleeting instant of frozen beauty transformed him into one of pioneers of snow photography. He succeeded in attaching a microscope to his camera in 1885, and soon thereafter was able to create the earliest confirmed photograph of a snowflake. Some researchers, though, ascribe that honor instead to the German natural scientist Johann Heinrich Flögel (1834-1918), who, it is claimed, took the first snow crystal photograph in 1879.

How To ?

Bentley knew that he needed a dark background for his work, in order to see the snowflakes as clearly as possible, and that he had to get his subjects beneath the lens as quickly as possible. What presented itself to him as the optimal solution was to cover a tray in black velvet and ferry the snowflakes directly to the camera on that. Sitting outside with the tray, he would watch the black surface through a magnifying glass until a perfectly symmetrical crystal appeared upon the velvet. He used a sliver of wood to move the snowflake onto a slide and brought that into the shed where he’d set up the microscope camera. He brought the microscopic image into focus using a string contraption he’d designed for use by gloved hands. A final challenge was posed by air itself; every careless breath could melt the crystal. Everything had to be accomplished with the greatest speed. Once preparations were all in place, he could expose the glass slide and the crystal upon it; the exposure time could last anywhere from between eight to a hundred seconds.

Earliest Depictions of Winter Landscapes in Art

An illustrated copy of the Tacuinum Sanitatis – an originally Arab text revolving around matters of health and well-being – happened to be owned by the same Bishop of Trento who, early in the fifteenth century, commissioned Master Wenceslas of Bohemia to execute a series of frescoes for the episcopal palace’s so-called Eagle Tower. The subject was the cycle of months, and although that theme could already be found in books and illustrated manuscripts, the Eagle Tower frescoes have been described as the first monumental depiction of the year in its calendar divisions. The fresco for the month of January, depicting a snowball fight, is also possibly the first large-scale painting showing a true winter scene.

Around the same time as the Trento frescoes, the Limbourg Brothers began to work on the Très Riches Heures, a book of hours commissioned by the Duc de Berry. The month of February in the lavishly illustrated calendar features a small farm in a frozen, snowy landscape, under a grey sky. Whereas the snow of Trento’s fresco vaguely resembles dirty cotton or wool strewn about the ground, the snow in the Limbourg’s February looks like it has fallen from the sky. Moreover, the snow is integrated into the actual composition of the work.

Sources:

Philip McCouat, “The Emergence of the Winter Landscape. Bruegel and his predecessors”, in: Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com, 2013/2014.

Kenneth G. Libbrecht, “The Formation of Snow Crystals. Subtle Molecualr Processes Govern the Growth of a Remarkable Variety of Elaborate Ice Structures”, in: American Scientist, Vol. 95, 2007, www.americanscientist.org

Kurt Tutschek, “Der Mann, der als Erster eine Schneeflocke fotografierte”, in: Der Standard, 2018, www.derstandard.de

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

How To: proper snow photography Nanook of the North (1922) The Formation of Snow Crystals Smilla's Sense of Snow Frances Chickering's Snow Flake Album (1864) How To Recognize a Fake Part I How To Recognize a Fake Part II

+49 89 29 73 42

+49 89 29 73 42