BULLETIN

Daniel Blau has assembled an outstanding collection of photographs bearing testimony to the attack

Kronos: Fire and Water

Strife and war are driving forces for mankind. Depictions of the hunt and scenes of war, of sword and spear, appear in our record even before recordkeeping, in the prehistoric cave paintings of Lascaux, the rock art of North Africa and Europe. We have, even from the earliest times, used our art to show our weapons at work exerting dominance over the natural world and our fellow man alike.

Sunday morning, December 7th, 1941: a grainy image shows Hawai’i from a bird’s-eye view. The island, the harbor, and a row of ships. Concentric waves. A torpedo has dropped into the water to leave those waves behind; in just a few moments it will hit one of those ships, and explode. The photo has captured the precise moment when the USA comes under direct attack by Japan. The attack on Pearl Harbor, more than any other single event, is what transformed a European war into a truly global one, a world war in all its senses and with its consequences.

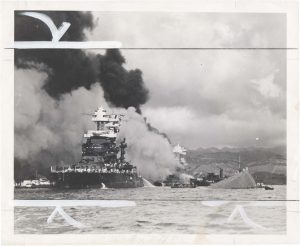

Daniel Blau has assembled an outstanding collection of photographs bearing testimony to the attack. U.S. Navy photographers are found here alongside the much rarer work of their counterparts within the Imperial Japanese Army. This contrast and compliment permits a vivid, haunting insight into this brief instant in history, this era-defining attack, and forms the basis for a deeper engagement with war photography at large and the artistic considerations and aspects involved.

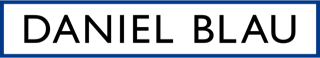

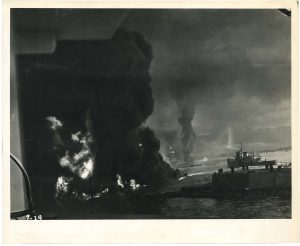

Nearly 81 years ago, Japan’s surprise attack on the US Pacific Fleet in Pearl Harbor brought about World War II’s turning point: the entry of the world’s most powerful military might, the USA, into the war. The unanticipated act of war lasted only about two hours. It came in two waves, claiming the lives of over 2,000 American soldiers and civilians. The photographs from our present collection illustrate almost every single military step taken by the two sides. The first Japanese bombers flew over Pearl Harbor that day at 7:48 am Hawaiian time. Their targets included, among others, seven US Navy battleships anchored in the vicinity of the Ford Islands, along the so-called ‘Battleship Row.’ In the course of those two attack waves, each lasting only a few minutes, 353 Japanese fighter jets and 28 submarines destroyed three US battleships and inflicted considerable damage on the remainder. The Americans were able, all the same, to shoot down 29 enemy planes.

The progression of weapons at human disposal has been matched by the progression of our illustration of them, from the dawn of art down to today. Rocks for bludgeoning and hurling gave way to the sword and the spear; the spear turns to arrow, to bullet and bomb and torpedo, until ultimately, in our own age, the long destructive evolution culminates in Fat Boy and Little Man, the atomic bomb in use, something like a response to the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The moment those first torpedoes dropped from Japanese planes above Hawai’i is also, then, the same decisive moment upon which the lives of hundreds of thousands in Hiroshima and Nagasaki hung. It is also, though, the moment in which the USA decided to demand an end to German hubris and arrogance. In a sort of paradox, then, the most important event of the 20th century was not so much a world peace, but rather the world war which engendered it.

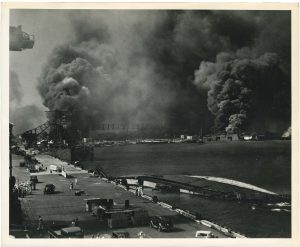

A deeply symbolic photograph, the earliest image from the attack, was shot from a Japanese warplane. The arial photograph clearly shows the torpedoes that hit the US Navy warships stationed along the coast. Our exhibition, however, begins with a photo taken from a Japanese newsreel, published much later in the war. Japanese fighter pilots can be seen being prepared for their mission on board an aircraft carrier. Pilots of the Shimpū Tokkōtai, the Japanese kamikaze unit, are given a symbolic sip of sake; they do not expect to survive their mission.

The most widely published of these photographs originates with photographers of the US Navy. It shows the USS Shaw, a small and fast warship of the class known as ‘destroyer,’ at the instant of its explosion in dry dock. The tragic moment, the exploding ship itself, all is framed by palm fronds and an otherwise idyllic scene. Holiday paradise and bloody conflict come directly face-to-face. Clouds, the fireworks of explosion, the bursting apart of the USS Shaw, all appears together like the elements of some old master’s oil painting.

It is here that the matter of artistic photography comes to the fore. The pictures made by both the Imperial Japanese Army Photographers and the US Navy photographers serve as valuable source material, chronologically documenting not only the attack on Pearl Harbor itself but also our very knowledge of it; through the visual language in use, through the spectacular motifs, through the thick swaths of smoke and formations of ocean cloud, in every shade and nuance of greyscale, these photographs also bring their enormous artistic and emotional worth before us, more than purely documentary evidence of the sinking wrecks, the uniformed young and old men alike on the docks and on doomed ships. These are artworks, showing their artists’ every effort in grasping towards a profound aesthetic in that hectic and instantly fleeting state of being which is war.

The timeline reasserts itself in another photo, taken May 24th, 1943: the slow and arduous salvage of the USS Oklahoma is underway. Throughout the 17 months following Japan’s surprise attack 16 of the 19 sunken ships were recovered by the Navy and put back into service. In the wake of such terrible events, a photograph like this can serve to grant man once again hope, a sense of security and faith in our capacity not only to survive but to rise up ever stronger.

Every single photo gathered here serves as an important document of its time. Most of these photographs also find elaboration through the original text or newspaper reports (slugs) included on the back; the word choice and the language of these texts opens the images up to us on yet another level, allowing each recipient to ‘read’ the image of the war again, as though through new eyes or with deeper understanding. Amongst all this abundance of art-historical objects and photographs, it remains the image itself, the reproductive depiction of an event – and this was as true then as it is today – which is taken as the ultimate proof of occurrence. We use words to name objects and occurrences, to give some meaning and purpose to them. But we also, in just the same way, rely upon the portrayal of history-laden events, whether in the form of something sketched or photographed, to bring us towards belief in the truthfulness of what has happened. Here we might look to the buried photographs of the Buchenwald concentration camp as an example. Images have enormous influence on the very way in which we see; they reflect political and military structures, can even be used, ultimately, as evidence in court proceedings, in investigation for instance of war crimes. The space always left for interpretation within a photograph’s frame, however, can also serve as space for propaganda. Photography always anchors itself, in our collective visual memory, as a genuine reproductive depiction of one moment. These different dimensions lead also to an understanding, though, that the recipient too must be held responsible: he must cast his thoughts to matters of seeing, of not-seeing and of not-wanting-to-see, and must pose to himself the question of what it is that in the last accounting remains as the real expressive significance of the photo. It is up to him to close the invisible hole in history that has opened up between the reproduced depiction and the real event itself.

“Kronos” is available for purchase as a set. Price upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

This offer is noncommital. We cannot guarantee the set is still available on request.

Other Diversions

Examine the facts and timeline of the Attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 The National WWII Museum - Pearl Harbor Attack, December 7, 1941 Naval History and Heritage Command View footage of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor U.S. Navy Pearl Harbor - The Attack and Aftermath Film “Pearl Harbor”, 2001 Pearl Harbor History

“Pearl Harbor Attack, Photographed from Japanese Bomber”, December 7, 1941,

vintage silver gelatin print on glossy paper, printed in 1942 in Germany,

17,1 (18,0) x 23,5 (24,4) cm © Unidentified Japanese Photographer, courtesy Daniel Blau Munich

+49 89 29 73 42

+49 89 29 73 42