BULLETIN

The Daguerreotype initially took over from silhouette paper cutting (Scherenschnitt) and portrait painting and drawing

Precious Pictures The Daguerreotype-Memento

When we speak of Daguerreotypes, we are referring to the earliest photographs, those made possible through the process advanced by and named after the Parisian Louis-Jacques-Mandé-Daguerre (1787-1851). The process saw a silver-coated copper plate exposed to iodine fumes, thereby creating a light-sensitive layer of silver iodide. The next step was to expose the copper plate to light from within a camera obscura. The plate – for the time being still looking exactly the same as it did before exposure – would be removed from the darkened box of the camera obscura and exposed to mercury fumes. At this point the picture was developed and visible to see; bathing the plate in a saline solution, then washing and drying it, would fix that picture permanently to the plate. Each daguerreotype was a completely unique item, not capable of further reproduction. The heritage of the invention extends beyond Daguerre himself – he made use of various physical, optical, and chemical laws and properties that were already known and understood. The camera obscura, for instance, had been in use as an aid for creating perspective drawings since the fifteenth century. The photosensitive properties of silver salts had been discovered by the German medical doctor Heinrich Schulze at the beginning of the eighteenth century. Even the photographic process itself was already known to science, thanks to Joseph Nicéphore Niépce. Niépce developed a method that required an exposure time lasting hours; thanks to Daguerre’s invention, that could be reduced to mere minutes.

Bodo von Dewitz and Fritz Kempe, Daguerreotypien. Ambrotypien und Bilder anderer Verfahren aus der Frühzeit der Photographie. Document of Photography 2, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg, 1983. p. 31

In a lecture at the Academy of Sciences and Fine Arts in Paris on August 19, 1839, the physicist François Dominique Arago at last announced the final details of the technical process that he had been involved in developing. With Daguerre, who gave his name to the first widely available and practical photographic process, a centuries-old scientific dream had come true. Daguerre had presumably begun the relevant experiments in 1825. Niépce and Daguerre had agreed to share the financial windfall of their research, should it prove successful. Arago, Daguerre and Niépce’s son – his father having, in the meantime, passed away – offered the invention to the French government in exchange for the payment of a lifelong pension. The French state bought the patent and released it to the public as a generous gift “à tout le monde.” Daguerre took his pension – 6,000 francs per annum – and retired to a private life in the countryside, where he died in 1851.

Volker Jakob, „Menschen im Silberspiegel: Die Anfänge der Fotografie in Westfalen.“

In Aus westfälischen Bildsammlungen, Vol. 1, ed. Wolfgang Linke, Eggenkamp Verlag, Greven, 1989. p. 11-12

When the process was made public, news reports began flying off the presses around the world, and a genuine ‘daguerreotype fever’ broke out in Paris. Contemporary reports speak of countless enthusiasts crowding the squares and streets with the first Daguerreotype cameras in hand. The demand for the devices seems to have been so great that production wasn’t able to keep pace. Some amateur photographers even attempted to create homemade versions. The Daguerreotype initially took over from silhouette paper cutting (Scherenschnitt) and portrait painting and drawing. Anyone could have life- like portraits of family and friends. This kind of memento gave rise to the fame and the propagation of the Daguerreotype. The metropolis of Berlin was the new art form’s first center in Germany, playing its part in ensuring the Daguerreotype method’s continuing spread and dissemination. Readers wanted new information and news reports constantly, and the press gave its all to keep its readers satisfied. Daguerreotype chemicals and the associated tools were readily available, supporting the experimentation of early photographers.

Jochen Voigt, Der gefrorene Augenblick. Daguerreotypien in Sachsen 1839-1860. Chemnitz, 2004. p. 13

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

How was it made? The Daguerreotype by Victoria & Albert Museum Daguerreobase Dark Valley Das finstere Tal Daguerreotype | Le Secret de la Chambre Noire

Writings on the Daguerreotype | Photoinstitut Bonartes (Albertina)

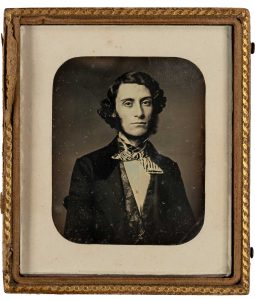

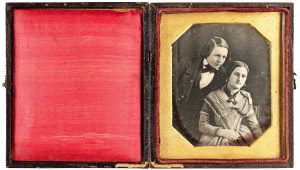

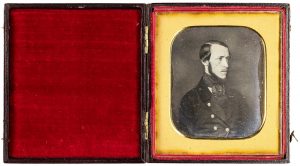

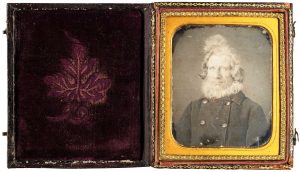

“Anonymous Portrait”, 1850s,

daguerreotype,

6,1 (9,5) x 5,0 (8,2) cm, ©Daniel Blau, Munich

+49 89 29 73 42

+49 89 29 73 42