BULLETIN

What is the aesthetic beauty of a circle, or of a turning, curving movement?

Tondo

Daniel Blau: Maybe we should start at the beginning. Do you remember when we first came up with the idea of putting round photos at the center of a show?

Serge Plantureux: The exact conversation? We were together, we were discussing several matters… you also had an interest in various subjects we discussed, like broken negatives. I think it was in the same conversation. We were looking for how to make a beautiful exhibition on a subject linked to a material aspect of photos.

DB: Yes, that was over 10 years ago!

SP: Oh yes, yes, more than 10 years!

DB: Yes… it was actually a fun time in Paris, lots of auctions.

SP: But I think it was even before Lehman Brothers.

DB: Yes, before Lehman Brothers. What is it that’s interesting about round photographs? Why did we decide on round pictures rather than damaged negatives? Which I still think is also a very good subject.

SP: Because of resources. It had to do with how many we hoped to find. How difficult it is, how rare the subject is. Damaged negatives… we started that as well, I think. But it didn’t develop into anything…

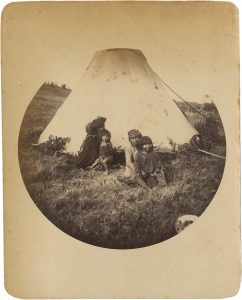

Roundness has a symbolic aspect to it. There are circular images made on purpose. There is something linked to the optical, something linked to the history of photography – for example, the Voigtländer camera in 1840. There is also the circular cutting-out of paper from a square original. So there are a lot of angles, and it is a very dynamic and creative subject.

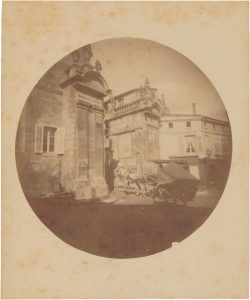

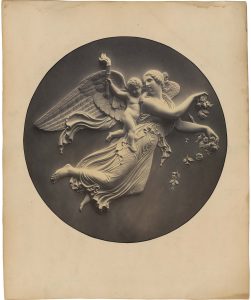

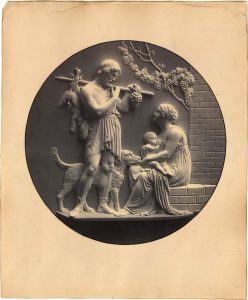

DB: I agree. Roundness in art – as with the tondo – has been around a long time. Maybe the most famous tondi are in the Uffizi, the Medusa’s Head by Caravaggio or the Madonna del Magnificat by Botticelli. You have a lot of round pictures in art history.

But round is also complicated. It is complicated in regard to framing, it is complicated in regard to process. You naturally have a lot of waste when you produce a round canvas or a round photograph, because you cannot divide a piece of paper into circles without loss. Therefore, the tondo is not very common in art, in photography. Even now it is not very common. But we found quite a few round photographs. Why do you think that’s the case?

SP: We found a few because we were kind of active, and efficient. We had access to many different collections and we had no time frame.

DB: Yes, no deadline…

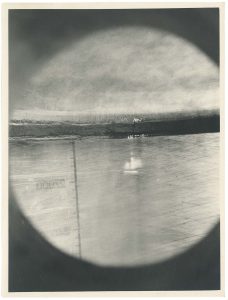

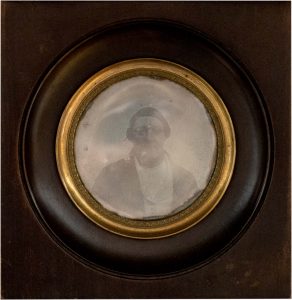

SP: We could cover all periods. It would be more difficult to put a substantial show together if you wanted to find roundness in modernist photography only, or in calotype. But once we accepted every period, we found the tondo in every generation, and found that, in fact, tondi from one generation to another are very different. In earlier times, some roundness was linked with microscopic investigation, because the image done with the microscope is already round by essence.

DB: Yes!

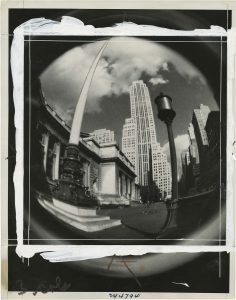

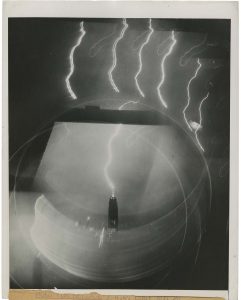

SP: Also, you had a lot of interest yourself, and I only discovered this on that occasion, in sténopé images. Most of the sténopé are round because of the pinhole. So, pinhole camera images are round with black margins… so they can be printed on square paper, but the image is centered in the middle of the print.

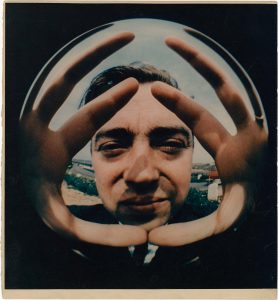

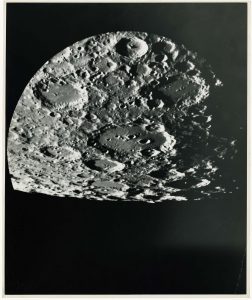

DB: What is the aesthetic beauty of a circle, or of a turning, curving movement? Isn’t it something that is quite natural to us? Beginning with the iris being round, and the eye being round like a sphere, and the head being roundish, the sun and the moon being round. We are surrounded by all these spherical and seemingly circular objects.

And don’t you think it’s surprising that, from the beginning of photography, the photo camera’s lens, which is naturally round, never square – and even a rectangular lens would create circular images – produces an image which is also round, a tondo, circular, yet results in rectangular prints? Wouldn’t you think that the carrier of the image, subsequently, should also be round? Sure, there are examples of circularity. Among the very earliest photography in France, you find daguerreotypes that are round. You mentioned the Voigtländer camera. But the history of the photography turned firmly to the square and the rectangular. Why, in photo history, is there not a continuation of circular photographs, based on the shape of the lens?

SP: Because it’s more expensive to produce Daguerrean round plates. Logistically it’s more difficult. It’s more difficult to store them. Except for eggs, most food is cubically stored, stacked.

DB: And they’ve even tried to make eggs cubical! So it’s an economic reason.

SP: I think so!

DB: That is probably correct! But photography is an art form. And wouldn’t an artist try to break out of economic boundaries to produce something that is artistically beautiful, or ugly, whatever his intention may be – but unrestricted by the common norm?

SP: It is a very interesting discussion, and it could make a beautiful exhibition. A real artist trying to break economic boundaries.

DB: Yes! The question is, again, why do photographers, as artists, stick to the boundaries of square or rectangular paper?

SP: Because every paper is produced square or rectangular.

DB: Didn’t artists in the early days make their own paper?

SP: Yes, but you still needed to buy the sheet of paper – they made an emulsion, not the paper itself.

DB: Yes, of course!

SP: Only in Daguerre’s time was there really an opportunity of choice, between the Voigtländer camera and the square Daguerre camera. But in other periods, every negative produced was either square or rectangular.

DB: There is the Kodak I and II, and they produce round images…

SP: … on square paper…

DB: Strangely enough, on square paper… exactly. But at least aesthetically they stay with the tondo, with the circular. I mean, round is just more pleasant to look at than rectangular. The anthroposoph knows that better than anybody else.

SP: Because of anthroposophy I’m thinking… Did we find round autochromes or not? I don’t think so…

DB: I don’t recall round autochromes. I mean, there are autochromes that are circular or oval in square or rectangular glass sheets. But I haven’t seen a round autochrome.

And you have the additional problem with the autochrome that you would have to cut the glass into a circle, which is not so easy.

SP: Oh yes, I’m also thinking of color. We found some round positive photograph images from Japan. The Japanese were interested in the idea of round images for glass positives.

DB: I can see that, with beautiful wooden frames, yes, I can see that! So even with Braun or Bisson, who did carbon prints on glass, you know – these stained-glass photographs of glaciers and alpine scenes that they produced – even with them I never saw stained-glass in the round.

SP: No, I agree…

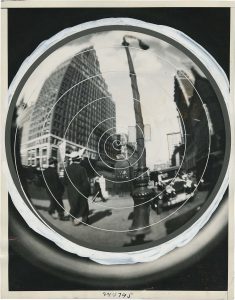

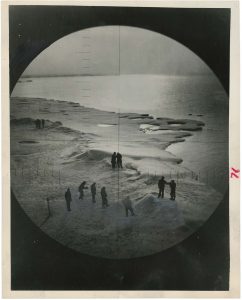

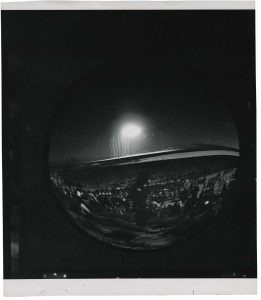

DB: Back to the round photographs that we managed to find. It was easier to find images in the round after the fish-eye lens became popular, at the beginning of the 1930s. The extreme wide angle gives a gravitating effect on the paper. If you cropped it square, you lose that. So, a lot of those first fish-eye lens images are actually circular on rectangular paper. For earlier periods it was not easy to find really good examples. Why do you think that is?

SP: Why? Because of the mimetic desire of photographers. You say some artists like to break the rules but most want to do the same thing… I don’t remember if we found what the first big success was, but I think there was a huge success with the fish-eye lens, and many people became interested in following up on that example. In the ‘60s and ‘70s it also connected with the spirit of the time.

DB: It’s a very simple and very impressive effect.

SP: Maybe the tondo was considered bourgeois by the avant-garde of the early twentieth century. That’s possible also!

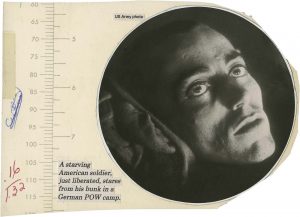

DB: And there is also another effect. A lot of photography was made for use in newspapers. Do you remember that, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, photographs which newspapers and magazines inserted into their texts were sometimes, even frequently, cropped round?

SP: Yes!

DB: In newspapers and magazines you’ll have a picture that is cropped circular because that somehow fits the design and the layout of the text, but I don’t recall finding any prints in newspaper archives that were cropped circular. So even if the original was square, the person doing the final layout would decide when to use it as a round image, and when not to…

DB: Again – economic reasons?

SP: If you consider an apartment, and you have a perfect wall, you can mix drawings, photographs, and paintings, but it’s not so easy to insert a round image on that wall… a round image or round frame can easily break the harmony.

DB: It could. Especially if it’s a little darker it looks like a hole. I mean, when you poke through something, the resulting hole is usually roundish. In painting, some modern and contemporary artists did round paintings. Damien Hirst did huge splatter paintings that are tondos – there’s also Baselitz, or Mondrian or Lichtenstein. But I know from experience no part of that is easy to do, beginning with the cutting and stretching of the canvas and up to the framing of the painting itself. And none of the framing studios are really equipped for roundness. It is extremely uncommon, extremely uncommon in art to find tondos these days. Some do it, but not many.

SP: If you consider social media, where you have billions of people playing around for likes on Instagram, it’s not so easy to insert round images into a river of images which are all of another format.

DB: That reminds me of a concert I heard yesterday. It was a piece by [Alfred] Schnittke, a rather modern composer. There was a break, to be followed by a piece by [Anton] Bruckner. And during the break, the people in front of us were talking to another couple. She was complaining that in Schnittke she heard no harmony, nothing musical that would be pleasing to her ears. She said: “Why do we have music if it isn’t harmonious to us?” And I’m thinking, the music that we hear today, just like the pictures that we’re looking at today, they are the result of a common understanding and usage. So, in the same way that we’re used to rectangles for economic reasons. The German word for this is Sehgewohnheiten. The way that we look and perceive is accustomed to the rectangular, and not to the circular. But let’s imagine everything had started out differently, if we weren’t used to ‘our’ kind of music but to what is produced in the Amazonian jungle, or somewhere else. Our Hör- and Sehgewohnheiten – our listening and viewing habits – would be quite different. Therefore, if [our world] wasn’t all industrialized the way it is, leading to square and rectangular everywhere in photography, maybe everything would be rounded, and if we saw a square photograph it would be surprising and irritating to us. I think it has a lot to do with habit and lobbies.

SP: Maybe yes, but can we go back to the personal house, the personal family flat? The round image is somehow very powerful in the way that it looks like a center. It looks like a direction – if you have one image isolated on the wall, for example, all by itself. Or you can have small ones, which are like punctuation. Round images are like the punctuation of a grammatical aesthetic phrase. A cultural aesthetic decoration of the room.

DB: Think of the Guggenheim, when the Guggenheim was built. Roundness is the main concept of the building. It is not easy to use. It is not easy to play with for exhibitions. It is possible. But the perception that you have, as a visitor, of the art in such a building, one that isn’t rectangular or square, is fundamentally different from when you walk into a square building, like the Guggenheim’s own Thannhauser annex. And there are cultures, there are people who are not used to angled-room buildings. I’m thinking of – you remember – the [Paul-Émile] Miot photographs that were done in Africa, in Senegal in 1870. In the background you see these clay houses that are like domes, so are not square. And can you imagine hanging square photographs in such a space. A round photograph would make much more sense.

SP: Yes.

DB: More related to the viewer.

SP: Ok, so I think the title can be “Most Photos are Squares Because Our Houses are Rectangles.”

DB: Yes, that’s exactly what I think. It is a decision that was made for economic reasons, most likely, that is embedded now in our visual understanding. Can you imagine if our telephones, our smart phones, instead of being square were round… ! If Apple decided to come out with a round telephone. Millions of people would buy that round telephone because it’s round and not square. That would change our visual understanding again, and I think the tondo would become more pleasant to us, and more common.

SP: Yes, perhaps, but I doubt it. For example „zooming“, I couldn’t have my telephone standing on the bar table here, if it was a disc or circle. It would roll right off!

“Tondo” is available for purchase as a set. Price upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

This offer is noncommital. We cannot guarantee the set is still available on request.

Other Diversions

The Globe Shakespeare Leonardo Da Vinci - The Vitruvian Man Albrecht Dürer - The Virgin and Child Crowned by Two Angels above a Landscape The Rotating Discs of Marcel Duchamp Vasily Kandinsky: Around the Circle Video: Vasily Kandinsky “Around the Circle” Movie Trailer “Vertigo” by Alfred Hitchcock Jules Verne - Around the World in Eighty Day 19th Century Street Photography With a Spy Camera The Guardian - In the round: centuries of circular design – in pictures The Met Museum - Kodak and the Rise of Amateur Photography Tate - Damien Hirst “Round” Uffizi Museum - Holy Family, known as the “Doni Tondo”

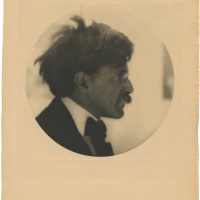

“Alfred Stieglitz”, 1908,

photogravure, printed in 1908,

15,9 (30,0) x 15,9 (21,0) cm, © Daniel Blau, Munich

+49 89 29 73 42

+49 89 29 73 42