BULLETIN

The sea, for those who live along the coast, is an important and even indispensable source of food

Fish Hooks of the Pacific Islands Vol II

Bonito fishermen [Bernatzik, 1934: fig. 30](1)

For example: The Solomon Islands:

The sea, for those who live along the coast, is an important and even indispensable source of food. In the Pacific Ocean, this is especially true. Fishing became, more than purely a necessity of life, a ubiquitous social activity across all the archipelagos and lone islands of the vast Pacific realm, with distinctive symbols, rituals, tools, and sites defining cultures from the West Coast of America to Southeast Asia.

Solomon Islands, composite bonito hooks, shell, natural fibres, turtle shell, nylon, plastic, glass beads

The fish hook, a simple prehistoric tool embedded in our shared human consciousness and essential for the survival of many island civilizations, spans and unites these various cultures, beliefs, and practices, allowing us a glimpse into the soul of the Pacific. In 2012, Daniel Blau and Klaus Maaz published their first book on the subject, “Fish Hooks of the Pacific Islands,” through Hirmer. Their work served as an introduction and meticulous evaluation of fish hooks from across the entire region. Their comprehensive and passionate approach exemplified to readers the degree to which these items are more than just tools, more than just functional, but are in fact art in themselves, where the magic of each hook’s form combines with the rituals of forefather craftsmen and fishermen past. The hooks represent the visible, material part of a tradition stretching back to the dawn of human culture, serving as a sort of chronocultural marker whose forms continue to evolve in space and time.

In this case, the description of each object is essential. The maritime lives of Oceania’s inhabitants compelled them to create artefacts unique to each shore, even for the smallest and most remote islands. The trade networks made possible by the ocean enabled in turn a rich cultural exchange, and the spread of knowledge and material goods. Despite that exchange, though, the unique nature of each island or island group’s own production – the material and design of each island’s hook, the subtleties of its form or interaction of its component parts – survived.

Solomon Islands, composite bonito hook, shell, turtle shell, natural fibres, glass beads

More difficult to gauge at first glance is the precise, human nature of their use. The uninitiated have no clear path to imagining the interaction between hook and the hand of its crafter, the particular form of a given hook and the perfect technique for casting it. How exactly was each hook used? Which hook was best suited for which fish? The continuation of Blau and Maaz’s illuminating work, “Fish Hooks of the Pacific Islands Vol II,”, helps make the unimaginable real. This second volume draws us back once again to the fascinating world of the Pacific, deepening our knowledge of its diverse and complex fishing cultures, practices, and rituals.

Solomon Islands (Uki/Ulawa)

Solomon Islands, composite bonito hook, shell, turtle shell, natural fibres, glass beads

For the people of the Pacific, fishing became more than just necessary – it became sacred. Perhaps the best example is to be found in the so-called bonito cult of the Solomon Islands. “Fish Hooks of the Pacific Islands: Vol. II” paints a vivid picture for us:

Whereas the indigenous island cultures of Polynesia and Micronesia succumbed to the intrusive influence of Western civilization in the second half of the nineteenth century, the traditional culture of the Solomon Islands survived well into the twentieth century, including the all-important and omnipresent bonito cult.

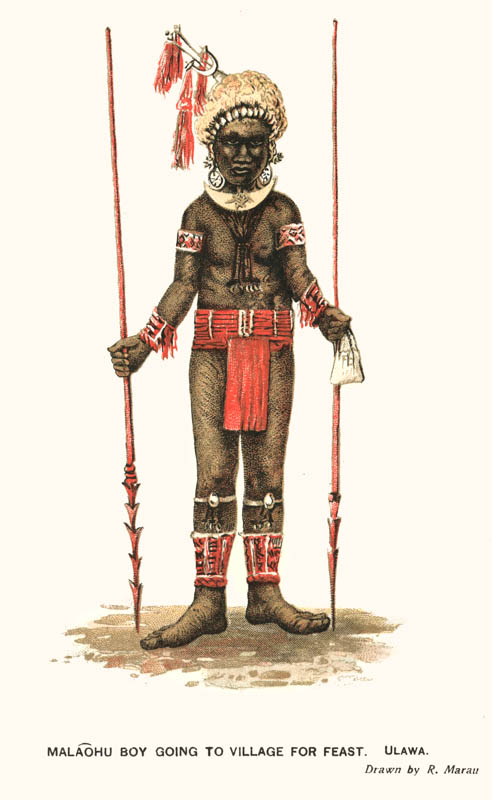

Particularly prominent in the islands of the southeast Solomons, ‘bonito cult’ is the term commonly used to refer to the entire, overarching environment of sacrality surrounding the bonito and everything related to it. This encompasses a vast range of practices, objects, and beliefs – sea spirits, fishing boats, traditions and rituals – but perhaps the most important and certainly the most visible single manifestation of the cult was to be found in the initiation ceremony of the Solomons, the sometimes months-long ritual process through which boys entered manhood – maraufu.

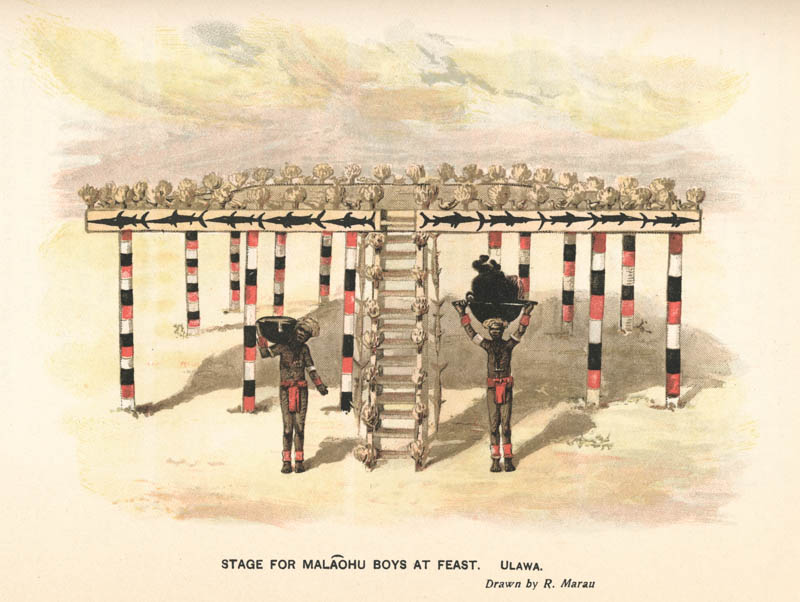

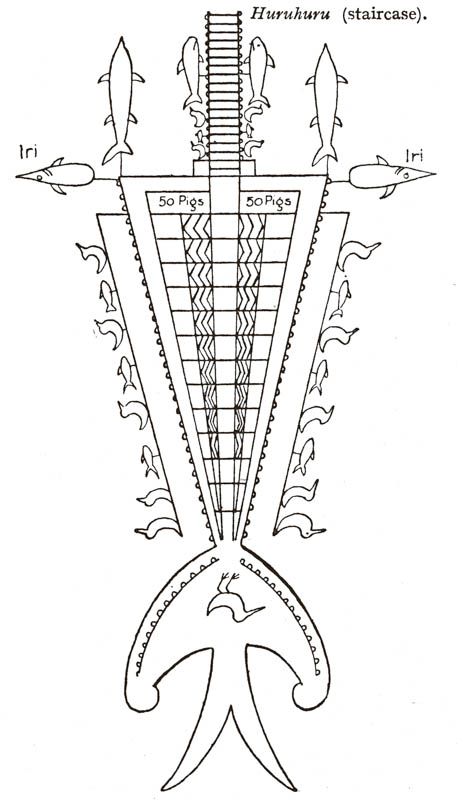

“Stage for Malaohu Boys at Feast”, Ulawa, drawn by R. Marau [Ivens, 1927:p.130-148] (2)

December through March is the windy season in the Solomons, the most important time of year for bonito fishermen. The season brings unfathomable schools of smaller fish past the islands’ coasts, and, following close behind them, large schools of sharks and other predatory fish at hunt, including, of course, the bonito. It is also in this season, therefore, that the initiation ceremony took place. Every boy had to undergo the initiation ritual, at about 13 or 14 years of age, in order to become a man, a process which, for the islanders, was intimately and inexorably bound up with the secrets of bonito fishing. Accordingly, the initiation process in its every stage and aspect is rife with bonito imagery and symbolism. The magnificent initiation platforms of the final ceremony embody this nearly mystical relationship in their very architecture. The basic form of the platform itself symbolizes a bonito, with its staircases acting as analogue to the great fish’s mouth. Entering the stairs, the boys, richly adorned and successfully emerged from their trials, symbolically enter the body of the fish. It is a moment that echoes an earlier stage and intermediate ceremony in the course of the long initiation process: after each boy returns from his first expedition alongside the experienced fishers, after he has caught his first bonito sat between the legs of his elder and grasping the rod with which the fish is hooked, he returns to shore, now an official maraufu or initiate-in-progress, where a priest awaits to cut the first-caught bonito open and anoint the new maraufu with its red, human-like blood, letting it drip across arms and legs, elbows and knees, cheeks, tongue – and flow even into the boy’s very mouth. The blood of the divinely-appointed bonito will, imbibed by those who will soon no longer be boys, make the body strong, keep joints and muscles young and sprightly. So now, at the culmination of their ordeals, do the youngest men of the island pass into the mouth of the fish.

right: [Fox, 1924: p. 348] (4)

Ngora-Ngora village on Ulawa Island [Bernatzik, 1934: pl. 13, fig. 13] (5)

This final ceremony, the end of the entire initiation process, is treated with great fanfare and celebration by the entire community. Hugo Bernatzik was one of the last observers of southeastern Solomon communities when they still could be conclusively called traditional. His photographs of ceremonial platforms show wooden carvings of frigate birds perched atop the platform’s poles, above support beams jutting out and ending in their own elaborate carvings of sharks and predatory fish. Bernatzik’s camera also accompanied him when he went with bonito fishermen out to sea. He succeeded in capturing the dynamic majesty of the catch so fully that even audiences from our own century must admit to being moved by the images that resulted.

Solomon Islands, composite bonito hook, pearl shell, turtle shell with nylon lashings

This elaborate, ceremonial culture of the bonito bore witness to an ancient tradition of fishing, one which finally began to collapse before the onslaught of Western civilization in the second half of the 20th century.“Fish Hooks of the Pacific Island: Vol. II” brings the extensive, profound research and discourse of Volume I to a triumphant conclusion, casting a much-needed light upon the extraordinary, diverse, and fragile human genius of the Pacific.

“Solomon Islands, one-piece fish hooks, shell, pigments and plant fibre

This limited-edition book is the ultimate resource on the fish hooks of the Pacific Islands. More than 450 fish hooks and dozens of related objects are presented here in their true size (1:1) for the very first time, spread across more than 450 pages and more than 80 full-page or fold-out plates, and accompanied by 500 accessory illustrations, 45 photos of people and islands, 50 maps, and comprehensive expert commentary.

Foreword and texts by Daniel Blau and Klaus Maaz.

Essays by Anthony JP Meyer and Sydney Picasso.

30 x 25 cm, hard cover with embossing and dust cover.

Please contact us for more information: fishhooks(at)danielblau.com

appl Druck GmbH in Wemding, Bavaria

Bibliography

(1) Bernatzik, Hugo Adolf. Südsee (Leipzig, 1934)

(2) Ivens, Walter George. Melanesians of the South-East Soloman Islands (London, 1927)

(3) Ivens, Walter George. Melanesians of the South-East Soloman Islands (London, 1927)

(4) Fox, Charles Elliot. The Threshold of the Pacific (London, 1924)

(5) Bernatzik, Hugo Adolf. Südsee (Leipzig, 1934)

ORDER HERE ON DANIELBLAU.COM

Other Diversions

MAGAZIN BLAU INTERNATIONAL British Museum - Online Collections Expedition Magazine, Penn Museum: Male Initiation in Aoriki (Salomon Islands) Friends of Tobi Island Frontiers in Marine Science: Na Vuku Makawa ni Qoli: Indigenous Fishing Knowledge (IFK) in Fiji and the Pacific Frontiers in Marine Science: The Role of Ancestral Seascape Discontinuity and Geographical Distance in Structuring Rockfish Populations in the Pacific Northwest Future Exhibitions and Installations at the Getty Centre, California Tavake Pakomio: Learning from our Ancestors: Exploring Ancestral Island Wisdom and Practices on Rapa Nui The Pacific Collection Access Project - French Polynesia, Google Arts & Culture The Serious, Sustainable (and Sometimes Celebratory) Indigineous Fishing Methods of Polynesia Women and Fishing in Traditional Pacific Island Culture Cook Islands: Traditional Fishing Methods 2012 Pacific Island Ethnic Art Museum, California

+49 89 29 73 42

+49 89 29 73 42