BULLETIN

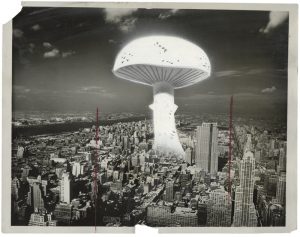

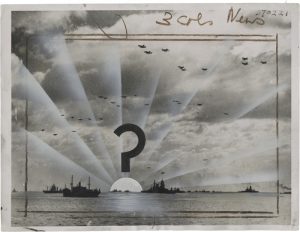

Digital technology has made the process of altering photographs faster and easier, more difficult to detect, and more accessible to more people – many more people – than at any point in history.

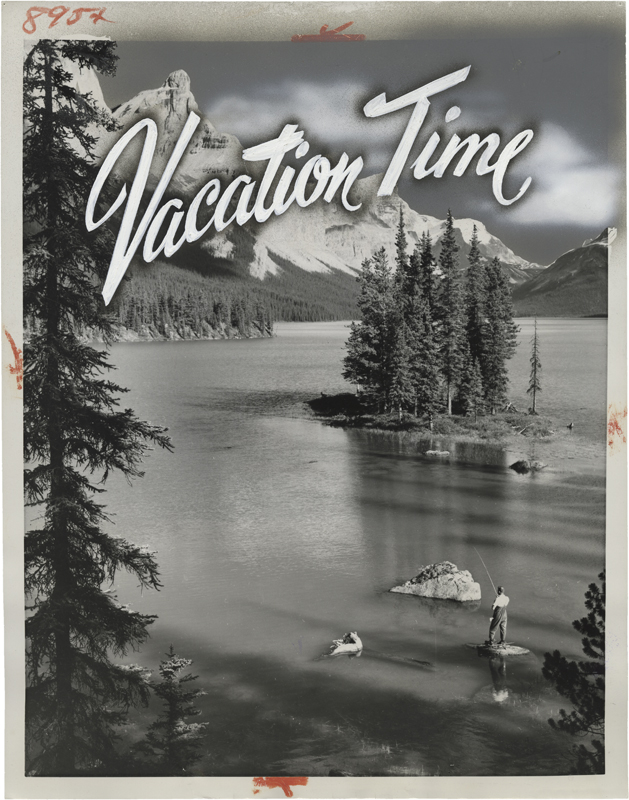

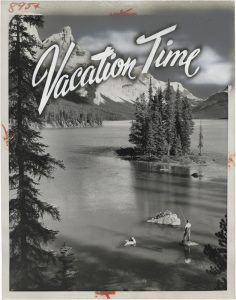

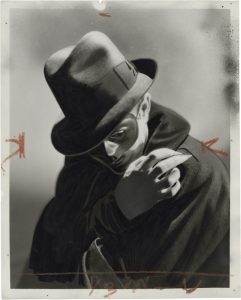

The Art of Airbrush

“I do not understand why this is supposed to interfere with the truth. … Photography is still a very new medium and everything is allowed and everything should be tried.”

(Bill Brandt, “A Statement,” (1970), in: Bill Brandt: Selected Texts and Bibliography,

ed. Nigel Warburton (Oxford: Clio Press, 1993), p. 31.)

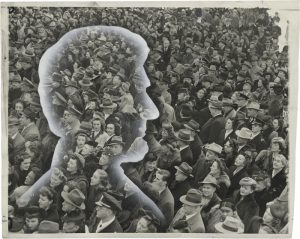

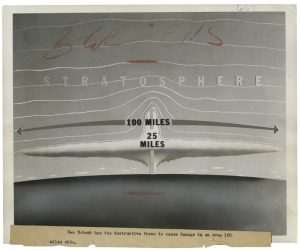

Digital technology has made the process of altering photographs faster and easier, more difficult to detect, and more accessible to more people – many more people – than at any point in history. Its beginnings, though, stretch back far further than the late twentieth century and the advent of digital photography. Though the technology may be new, the desire to modify camera-captured images is as old as photography itself, and the determination of artists and inventors through the generations has brought new techniques and innovations at every step. Nearly every kind of photographic manipulation we now associate with Photoshop was once part of photography’s analog repertoire, from slimming waistlines and smoothing away wrinkles to replacing backgrounds and adding people to group shots (or, in other cases – removing them!). From the earliest days of photography onward, photographers have devised a staggering array of techniques, including multiple exposure, photomontage, combination printing, airbrush retouching, and more.

(Adapted from: Mia Fineman, Faking it. Manipulated Photography before Photoshop (New York: Metropolitan Museum, 2012), p. 5-6.)

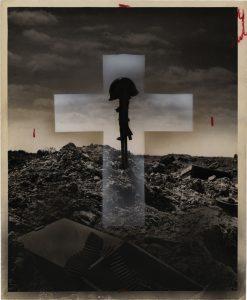

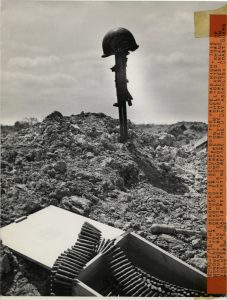

Winston Smith, protagonist of George Orwell’s novel Nineteen Eighty-Four and civil servant in Oceania, the totalitarian superstate ruled by ‘the Party’ works in the Records Department of the Ministry of Truth, where he spends his days ‘rectifying’ historical documents to accord with the Party’s latest version of reality – falsifying the past to square it with the ideological needs of the present. One day, while rewriting a newspaper report concerning a speech by Big Brother, he invents a fictious war hero, Comrade Ogilvy, whose death the rectified speech will commemorate. “It was true that there was no such person as Comrade Ogilvy,” Winston reflects, “but a few lines of print and a couple of faked photographs would soon bring him into existence. […] Comrade Ogilvy, who had never existed in the present, now existed in the past, and when once the act of forgery was forgotten, he would exist just as authentically, and upon the same evidence, as Charlemagne and Julius Caesar.“

(George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), quoted in Mia Fineman, Faking it. Manipulated Photography before Photoshop (New York: Metropolitan Museum, 2012), p. 89.)

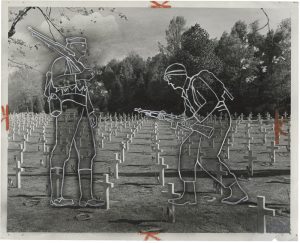

When Orwell was writing, in the late 1940s, the Stalinist project of historical revisionism was in full swing in the Soviet Union, and the faking of photographs was a key tactic in the regime’s systematic falsification of the past. A manipulated photograph could endow political fiction with an air of factual authenticity. The falsification of photographs was widespread in the Soviet Union, but it was hardly unique to that country or that political system. The temptation to ‘rectify’ photographic documents has proved irresistible to modern demagogues of all stripes, from Adolf Hitler to Mao Zedong to Joseph McCarthy.

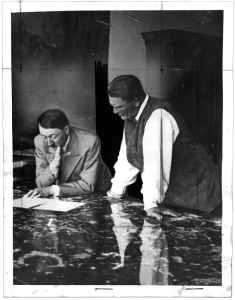

In a relatively benign example discovered among the files of Hitler’s official photographer, Heinrich Hoffmann, Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels is excised from a publicity photograph taken at the Berlin home of filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl in 1937, possibly in order to combat rumors that Goebbels and Riefenstahl were having an affair.

(Adapted from: Mia Fineman, Faking it. Manipulated Photography before Photoshop (New York: Metropolitan Museum, 2012), p. 89-90.)

Airbrush:

Tool that combines a liquid medium with air and forces it through a tiny orifice to produce a fine mist for smooth application of the medium to a substrate. First patented by the American Francis E. Stanley in 1876 and used for coloring and coating photographs as well as for retouching, the airbrush was a precursor to aerosol spray paint.

(Adapted from: Mia Fineman, Faking it. Manipulated Photography before Photoshop (New York: Metropolitan Museum, 2012), p. 270.)

All photographs are available for purchase. Prices upon request. For further information please send an email to: contact@danielblau.com

All offers are noncommital. We cannot guarantee the items are still available on request.

Other Diversions

PhD Thesis on Airbrushing Airbrushinfo.net Blau Bulletin #1 (Retouching in Photography) Airbrushed From History (Article The Independent) How Politicians Are Retouching Their Photos Artists Working With Airbrush Barrie Cook (The Guardian) Digital Retouching of Skin with Airbrush

+49 89 29 73 42

+49 89 29 73 42